Open Source Business Models: Difference between revisions

| (20 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Source== | ==Source== | ||

<center> | |||

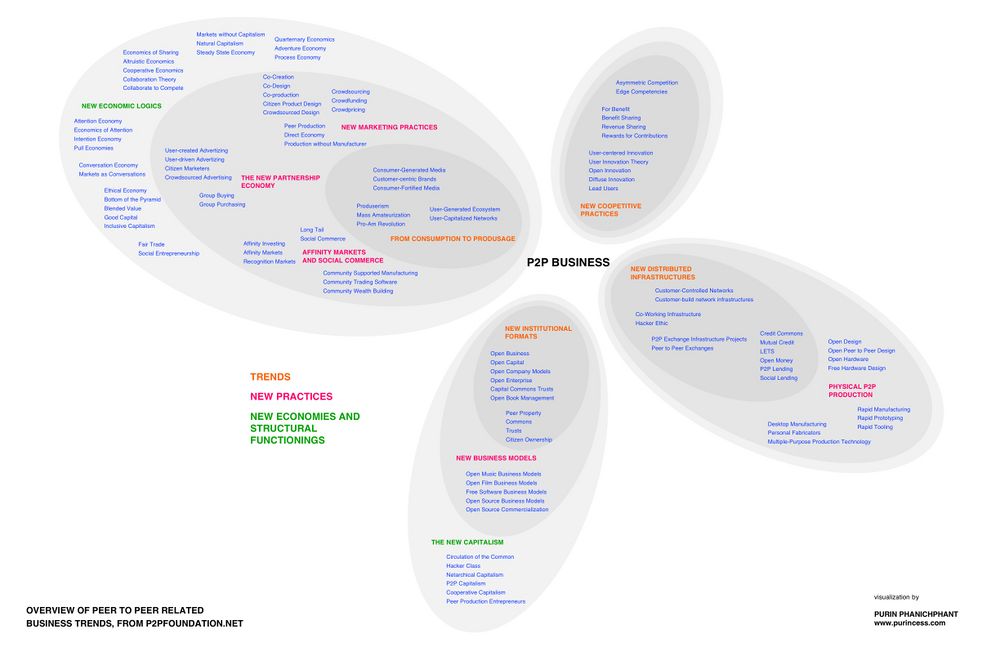

[[image: P2PBusinessVisualization1.jpg|1000px]] | |||

[[Media:P2PBusinessVisualization1.jpg|larger version of this graph]] | |||

</center> | |||

Most of the material below is from http://rsss.anu.edu.au/~janeth/OSBusMod.html | Most of the material below is from http://rsss.anu.edu.au/~janeth/OSBusMod.html | ||

| Line 11: | Line 13: | ||

We've selected the citations that are generally significant for all sectors and for software, not those related to [[Open Source Biotechnology]], which is the main topic of the research. | We've selected the citations that are generally significant for all sectors and for software, not those related to [[Open Source Biotechnology]], which is the main topic of the research. | ||

See also our article on [[Open Source Software]] which explains the competitive benefits of using open source software. It | See also our article on [[Open Source Software]] which explains the competitive benefits of using open source software. It also explains a typology distinguishing community based from corporate based open software models. | ||

Janet Hope recommends the classic essay by Frank Hecker, [http://www.hecker.org/writings/setting-up-shop.html Setting Up Shop], as the best account of open source business models. | Janet Hope recommends the classic essay by Frank Hecker, [http://www.hecker.org/writings/setting-up-shop.html Setting Up Shop], as the best account of open source business models. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 19: | ||

==Problems with the older model of IP rents== | ==Problems with the older model of IP rents== | ||

"Standard business models ... aim to extract economic benefit primarily from the value of tools as end products (ie their value as final goods). The business creates the tool, fences it around with intellectual property protection, and derives revenue by selling the tool or, more commonly, charging | "Standard business models ... aim to extract economic benefit primarily from the value of tools as end products (ie their value as final goods). The business creates the tool, fences it around with intellectual property protection, and derives revenue by selling the tool or, more commonly, charging fees for access under a licensing agreement. | ||

From a business perspective, this IP-rent extracting model has a number of advantages. The relevant property transactions can be tailored in a range of ways, e.g. to allow for price discrimination. Fees can be charged independent of any services provided, which makes it possible for a new business to start small but grow quickly. Most importantly, the price charged for the product need not bear any proportional relationship with the initial costs -- so profit margins can potentially get very large. | From a business perspective, this IP-rent extracting model has a number of advantages. The relevant property transactions can be tailored in a range of ways, e.g. to allow for price discrimination. Fees can be charged independent of any services provided, which makes it possible for a new business to start small but grow quickly. Most importantly, the price charged for the product need not bear any proportional relationship with the initial costs -- so profit margins can potentially get very large. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 27: | ||

Less obviously, restricting access to intellectual property poses an immediate economic challenge to the company: it alone must generate all of the value offered to its customers. This is particularly hard for smaller companies because their resources - money, people, time - are more limited, but it is a cost for any company, no matter what its size." | Less obviously, restricting access to intellectual property poses an immediate economic challenge to the company: it alone must generate all of the value offered to its customers. This is particularly hard for smaller companies because their resources - money, people, time - are more limited, but it is a cost for any company, no matter what its size." | ||

(http://rsss.anu.edu.au/~janeth/OSBusMod.html) | (http://rsss.anu.edu.au/~janeth/OSBusMod.html) | ||

==Advantages of the new model of engaging outsiders== | ==Advantages of the new model of engaging outsiders== | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

These include preventing competitors from getting a choke-hold on the technology in question, redirecting competition from an area in which the company is weak to one in which is strong (for example, the company may be too small to provide a comprehensive package of tools for any given job, but strong at customising the tools it does own), overcoming resource constraints by creating an opportunity for several smaller firms to combine resources against a larger competitor or by lowering research and development overheads, attracting customers away from an established competitor (ie building "mindshare") and growing the market for closed products built on the open source platform." | These include preventing competitors from getting a choke-hold on the technology in question, redirecting competition from an area in which the company is weak to one in which is strong (for example, the company may be too small to provide a comprehensive package of tools for any given job, but strong at customising the tools it does own), overcoming resource constraints by creating an opportunity for several smaller firms to combine resources against a larger competitor or by lowering research and development overheads, attracting customers away from an established competitor (ie building "mindshare") and growing the market for closed products built on the open source platform." | ||

=Typology of Business Models= | |||

=Typology of Business Models 1= | |||

Éric Barroca: | |||

"1. Proprietary software (!): Build and distribute proprietary software leveraging open source ones (be it complete apps or just extensions). Take Day Software, quietly producing tons of good open source infrastructure components, they sell a great proprietary app. Or IBM with Geronimo / Websphere. Or Oracle. SpringSource and most “Commercial Open Source” companies fall into this category too. I think it’s the easiest way to make money out of open source. | |||

2. Support & Packaged Services: Sell support as subscription and high-value packaged services (monitoring, inventory, etc.) for open source software you’re producing. JBoss was the flagship in this business with quite a success making money with it. This is Nuxeo’s business too. | |||

3. Proprietary distribution: assemble open source software into a proprietary stack. It’s all open source software, but the recipe to assemble the different components together and deliver a coherent and supported stack is kept secret. This can also include some “proprietary services” such as automated updates or monitoring. This is RedHat’s business. Sun seems to look toward this way too (see Solaris and the recent WebStack). | |||

4. Proprietary tooling: sell proprietary tools that help running / operating / managing open source products. These tools are usually development tools, administration tools or deployment tools. | |||

5. SaaS: package open source software to deliver apps as a service. This is the business of managed apps hosting (to make apps run) and packaged services (to deliver great customer support and business domain knowledge). This is also Nuxeo’s business." | |||

(http://blogs.nuxeo.com/ebarroca/2009/08/commercial-open-source-or-just-a-free-demo.html) | |||

=Typology of Business Models 2= | |||

For a shorter typology based on selling strategies, see [http://p2pfoundation.net/Open_Source_Commercialization#Selling_Models Overview of Selling Models] in our article on [[Open Source Commercialization]] | For a shorter typology based on selling strategies, see [http://p2pfoundation.net/Open_Source_Commercialization#Selling_Models Overview of Selling Models] in our article on [[Open Source Commercialization]] | ||

| Line 159: | Line 177: | ||

=Typology of Licensing Strategies for Businesses= | =Typology of Licensing Strategies for Businesses= | ||

See: [[Open Source Licensing Strategies]] | |||

=Competitive Strategies= | =Competitive Strategies= | ||

See: [[Open Source Competitive Strategies]] [http://www.osbr.ca/ojs/index.php/osbr/article/view/404/365] | |||

=Sustainability Criteria= | =Sustainability Criteria= | ||

| Line 345: | Line 202: | ||

=More Information= | =More Information= | ||

* Article: [[Growing Revenue with Open Source]], Mekki MacAulay. Open Source Business Resource, June 2010 [http://www.osbr.ca/ojs/index.php/osbr/article/view/1140/1091] (seven strategies) | |||

#[http://www.joelonsoftware.com/articles/StrategyLetterV.html Why do capitalist entreprises support open source?]: classic arguments by Joel Spolsky. | |||

#[http://www.pentaho.org/beekeeper The Bee Keeper]: A Description of Professional Open Source Business Models | |||

Also: | |||

#See our entries on [[Open Source Commercialization]] and [[Open Source Software]] | #See our entries on [[Open Source Commercialization]] and [[Open Source Software]] | ||

| Line 352: | Line 216: | ||

#Insightful presentation by Brent Williams, open source software equity analyst, on the economics of open source software at http://stephesblog.blogs.com/presentations/BrentWilliamsEclipseConV02.pdf | #Insightful presentation by Brent Williams, open source software equity analyst, on the economics of open source software at http://stephesblog.blogs.com/presentations/BrentWilliamsEclipseConV02.pdf | ||

#Graph with commentary: [http://www.gandalf-lab.com/blog/2007/07/comparing-commercial-open-source-and.html Comparing traditional software companies with commercial open source software companies] | #Graph with commentary: [http://www.gandalf-lab.com/blog/2007/07/comparing-commercial-open-source-and.html Comparing traditional software companies with commercial open source software companies] | ||

Book chapters: | Book chapters: | ||

| Line 359: | Line 224: | ||

#Analysis of OS Business models, at http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap15.pdf | #Analysis of OS Business models, at http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap15.pdf | ||

#Allocation of resources in OS mode, http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap16.pdf | #Allocation of resources in OS mode, http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap16.pdf | ||

#Open Source as a Business Strategy, by Brian Behlendorf, at http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/opensources/book/brian.html | |||

Other Research: | |||

#[http://opensource.mit.edu/papers/dahlander2.pdf Appropriating the Commons: Firms in Open Source Software]. Linus Dahlander. | |||

#[http://opensource.mit.edu/papers/paper_euram_2007.pdf Open Source and the software industry. How firms do business out of an open innovation paradigm]. By Andrea Bonaccorsi, Monica Merito, Cristina Rossi, Lucia Piscitello. | |||

Cases: | Cases: | ||

| Line 364: | Line 236: | ||

#Mozilla/Apache case studies, at http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap10.pdf | #Mozilla/Apache case studies, at http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap10.pdf | ||

#Microsoft shared source, http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap17.pdf | #Microsoft shared source, http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap17.pdf | ||

| Line 369: | Line 243: | ||

[[Category:Business]] | [[Category:Business]] | ||

[[Category:Open]] | |||

[[Category:Business Models]] | |||

[[Category:P2P Market Approaches]] | |||

[[Category:Peerproduction]] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:40, 24 July 2011

Open Source Business Models: why they make sense

Source

Most of the material below is from http://rsss.anu.edu.au/~janeth/OSBusMod.html

Chapter: Open Source as a Business Approach from the PhD thesis from Janet Hope at janet dot hope at anu.edu.au

We've selected the citations that are generally significant for all sectors and for software, not those related to Open Source Biotechnology, which is the main topic of the research.

See also our article on Open Source Software which explains the competitive benefits of using open source software. It also explains a typology distinguishing community based from corporate based open software models.

Janet Hope recommends the classic essay by Frank Hecker, Setting Up Shop, as the best account of open source business models.

Problems with the older model of IP rents

"Standard business models ... aim to extract economic benefit primarily from the value of tools as end products (ie their value as final goods). The business creates the tool, fences it around with intellectual property protection, and derives revenue by selling the tool or, more commonly, charging fees for access under a licensing agreement.

From a business perspective, this IP-rent extracting model has a number of advantages. The relevant property transactions can be tailored in a range of ways, e.g. to allow for price discrimination. Fees can be charged independent of any services provided, which makes it possible for a new business to start small but grow quickly. Most importantly, the price charged for the product need not bear any proportional relationship with the initial costs -- so profit margins can potentially get very large.

However, because the IP-rent extracting strategy relies directly on restricting access to the tool, it also has a number of costs. From a public interest perspective, the main costs are higher prices in the short term (the well-recognised cost of granting a monopoly) and threats to future innovation in the longer term. In the longer term, of course, the company itself also has an economic interest in ensuring continuing innovation so it can remain competitive as the market changes.

Less obviously, restricting access to intellectual property poses an immediate economic challenge to the company: it alone must generate all of the value offered to its customers. This is particularly hard for smaller companies because their resources - money, people, time - are more limited, but it is a cost for any company, no matter what its size." (http://rsss.anu.edu.au/~janeth/OSBusMod.html)

Advantages of the new model of engaging outsiders

"The open source approach offers an opportunity to address these economic challenges by expanding the resources available to the company to include resources that lie outside the firm boundary. In this model, the company allows users access to its intellectual property, and in return it gets help with developing the tool instead of having to do everything on its own. Open source licences support this strategy in two ways. The first is purely practical: users cannot become codevelopers of a tool unless they have access to that tool in a form that they can understand and modify. In the software context, this issue is addressed by the requirement to provide access to source code; an open source biotechnology licence would also need to guarantee such access one way or another. The second relates to users' incentive to contribute to a co-operative effort: if potential contributors expect to be prevented from using the tool that they helped to create, they will be reluctant to contribute in the first place. Seen in this light, the open source prohibition on terms restricting use, redistribution and modification of licenced subject matter is a way of shoring up the motivation of potential contributors.

Not only do open source business models offer a way around resource constraints for individual businesses, they also preserve many of the advantages (from a public interest/long term innovation perspective) of straight-out donations of intellectual property to the public domain as per traditional academic practice. Importantly, open source licensing of intellectual property does not entail giving up ownership of the property; rather, ownership rights are exploited (through licensing agreements) to harness the input of a large number of users or potential users to create and/or improve the tool. Yet because open source licences allow use, redistribution and modification of subject matter without imposing any fee, intellectual property that is subject to such licences has been characterised in efforts to map the public domain as "contiguous territory".

There is, of course, a downside from the business perspective. Clearly, open source prohibitions on restrictive licensing terms are incompatible with standard "proprietary" business models." (http://rsss.anu.edu.au/~janeth/OSBusMod.html)

Characteristics of the new Open Source Business Models

Maximising use value

The first essential element of an open source business plan is to maximise the use value of the intellectual property in question (in the context of this study, a biotechnology reserach tool). This section first explains how harnessing the input of many users can enhance the use value of a tool, then turns to the question of how to harness that input by building a community of users/codevelopers.

The open source approach of involving a large number of users in the development of a research tool contributes to quality improvements in two ways. First, "given enough eyes, all bugs are shallow": as demonstrated by the Linux project, a large group of users can eliminate design flaws and introduce enhancements very rapidly. Second, the existence of a development community that includes both users and owners of the tool allows users to communicate needs and priorities to owners so that overall development efforts are more likely to be directed towards the most useful tasks.

It also improves mproved understanding, availability, and generates network effects.

Building a user community

A business that decides to license its intellectual property on open source principles in order to maximise the use value of the property is effectively setting out to become the "owner" (though not necessarily in a technical legal sense: users still own their own contributions, unless there is an assignment of contributions as in the case of the Free Software Foundation) or leader of an open source project. In the software world, the role of a project leader is to:

1. Provide the base intellectual content for the project and continue to seed it with new contributions. This may be relatively straightforward if the tool already exists and managment of the tool is changing from a standard proprietary model to an open source model, but may involve more effort in relation to a new tool. Experience in the software context suggests that cooperative development is most successful if developers can work with an existing body of material.

2. Set up and maintain an effective community structure that maximises users' motivation to contribute to the project. The next two sections address these issues.

3. Keep up morale. As Al Gilman, founder of the Alliance for Cellular Signalling, has said, there should be "money in the budget for pom-poms". To do this effectively, project leaders need certain social and communication skills (ie "leadership qualities"!).

Subtasks:

(a) motivating participants (b) structure and infrastructure

Creating Common Platforms

"Apart from direct revenue-generating activities in secondary markets (discussed below), businesses that choose to adopt an open source approach to some or all of their intellectual property may reap other economic rewards.

These include preventing competitors from getting a choke-hold on the technology in question, redirecting competition from an area in which the company is weak to one in which is strong (for example, the company may be too small to provide a comprehensive package of tools for any given job, but strong at customising the tools it does own), overcoming resource constraints by creating an opportunity for several smaller firms to combine resources against a larger competitor or by lowering research and development overheads, attracting customers away from an established competitor (ie building "mindshare") and growing the market for closed products built on the open source platform."

Typology of Business Models 1

Éric Barroca:

"1. Proprietary software (!): Build and distribute proprietary software leveraging open source ones (be it complete apps or just extensions). Take Day Software, quietly producing tons of good open source infrastructure components, they sell a great proprietary app. Or IBM with Geronimo / Websphere. Or Oracle. SpringSource and most “Commercial Open Source” companies fall into this category too. I think it’s the easiest way to make money out of open source.

2. Support & Packaged Services: Sell support as subscription and high-value packaged services (monitoring, inventory, etc.) for open source software you’re producing. JBoss was the flagship in this business with quite a success making money with it. This is Nuxeo’s business too.

3. Proprietary distribution: assemble open source software into a proprietary stack. It’s all open source software, but the recipe to assemble the different components together and deliver a coherent and supported stack is kept secret. This can also include some “proprietary services” such as automated updates or monitoring. This is RedHat’s business. Sun seems to look toward this way too (see Solaris and the recent WebStack).

4. Proprietary tooling: sell proprietary tools that help running / operating / managing open source products. These tools are usually development tools, administration tools or deployment tools.

5. SaaS: package open source software to deliver apps as a service. This is the business of managed apps hosting (to make apps run) and packaged services (to deliver great customer support and business domain knowledge). This is also Nuxeo’s business." (http://blogs.nuxeo.com/ebarroca/2009/08/commercial-open-source-or-just-a-free-demo.html)

Typology of Business Models 2

For a shorter typology based on selling strategies, see Overview of Selling Models in our article on Open Source Commercialization

Open source business models include:

1. support seller

- most if not all open source licences would work for this model

- revenue is generated by selling two broad categories of items -- physical goods and/or services

- vendors differentiate themselves by providing more complete and easier to use research tool distributions (e.g. kits) and by the quality and pricing of their service offerings

- only limited ability to use value driven pricing because there is price competition from other vendors offering comparable goods and services and lemons to what users are willing to pay for those goods or services, but if vendors's reputation is good that can be used to justify higher prices

2. Loss leader/market positioner

- no charge open source product is used as a loss leader for traditional commercial software

- open source product generates little or no revenue part customers are attracted for other products sold using the traditional model

- if the other products are built on the open source product, the open source license chosen must allow the intellectual property to be used in proprietary products using standard licences, therefore should avoid the use of GPL or other copy left style licences

- generates some revenue from the open source product as in the support sellers model, e.g. selling services, but typically the bulk of revenue generated would-be through sales of other close source products -- increased sales would be because of

- vendors differentiate themselves based on the product in the traditional product line and can also employ value driven pricing with such products

3. Widget frosting

- intended for companies in business primarily to sell hardware but use the open source model for enabling tools distributed at no charge along with the hardware

- most revenue is generated through sales of the hardware

- hardware sales may be increased by open sourcing as in the loss leader scenario -- increases the base of developers familiar with the hardware and able to make it perform to full capacity

- vendors can differentiate themselves based on the attributes of the underlying hardware

- vendors is selling physical goods for which competitive products exist in most cases so the pricing is typically more cost driven than value driven

4. Accessorising

- distributed physical items (ie not software or services) associated with and supportive of open source software

- piggyback on the open source software developed and maintained by others

5. Service enabler

6. sell it, free it

- essentially the loss leader model repeated and extended through time

- company deliberately structures its development and licensing practices so as to release research tools first under traditional right to use licences and then convert them to open source when they reach the point in their life cycle where the benefits of developing them in an open source environment outweighed the direct license revenue they produce new line-newly freed open source products still adding value to the remaining proprietary products as in the loss leader model

7. Brand licensing

- a company makes the research tool itself open source but retains the rights to its product trademarks and related intellectual property and charges other companies for the right to use those trademarks in creating derivative products distributed under the same brand name

- this requires that the product exist in two different forms with two different names -- official (trademarked), e.g. Netscape and unofficial, e.g. Mozilla

8. Research tool franchising

- draws on the brand licensing and support sellers models

- you are a support seller with a great reputation

- you expand not through direct hiring and acquisition but through franchising -- i.e. authorising other developers to use your brand names and trademarks in creating associated organisations doing open source support and custom software development in particular geographic areas or vertical markets

- you make money by licensing your brand and trademarks and also by supplying your franchisees with training and services; revenues come from sales of franchises and royalties based on franchisees' revenue

Typology of Licensing Strategies for Businesses

See: Open Source Licensing Strategies

Competitive Strategies

See: Open Source Competitive Strategies [1]

Sustainability Criteria

What makes an open source project (both for community and company) sustainable?

From Tere Vaden et al at http://numenor.lib.uic.edu/fmconference/viewabstract.php?id=50

"1) Social sustainability of a community is affected by factors like size, age, decision-making structures, and the variety and balance of skills and goals. Our empirical data shows that there are big differences in values, motivation and organisational structures between volunteer and hybrid communities.

2) Cultural sustainability of a community is defined by the traditions and history that over a period of time shape its social and ethical norms and practices. Tradition is sometimes codified in texts like the Debian Social Contract.

3) Legal sustainability depends on solid licensing policy, risk management against software patents and code misappropriation, and the ability to defend the community in a formal way when informal conflict resolution is not enough.

4) Economical sustainability depends on the economical dependencies of the community. A strongly hybrid community may receive contributions from many companies and is consequently partly dependent on the success of those companies. At the same time, successful company collaboration may take the community forward quickly.

5) Technological sustainability depends on choices of, e.g., programming language, software architecture, version control solutions, and communication solutions. Choices made early in the development process affect the process later as the community grows larger." (http://numenor.lib.uic.edu/fmconference/viewabstract.php?id=50)

More Information

- Article: Growing Revenue with Open Source, Mekki MacAulay. Open Source Business Resource, June 2010 [2] (seven strategies)

- Why do capitalist entreprises support open source?: classic arguments by Joel Spolsky.

- The Bee Keeper: A Description of Professional Open Source Business Models

Also:

- See our entries on Open Source Commercialization and Open Source Software

- Technology Commercialization Theory could explain the commercialization of Open Source Software

- Frank Hecker, Setting Up Shop, is a classic account of open source software business models, last updated in 2000

- Bruno Perens, The Emerging Economic Paradigm of Open Source is a more recent essay

- Insightful presentation by Brent Williams, open source software equity analyst, on the economics of open source software at http://stephesblog.blogs.com/presentations/BrentWilliamsEclipseConV02.pdf

- Graph with commentary: Comparing traditional software companies with commercial open source software companies

Book chapters:

- Economics of open source, at http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap3.pdf

- Open source as user innovation – von Hippel, at http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap14.pdf

- Analysis of OS Business models, at http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap15.pdf

- Allocation of resources in OS mode, http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap16.pdf

- Open Source as a Business Strategy, by Brian Behlendorf, at http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/opensources/book/brian.html

Other Research:

- Appropriating the Commons: Firms in Open Source Software. Linus Dahlander.

- Open Source and the software industry. How firms do business out of an open innovation paradigm. By Andrea Bonaccorsi, Monica Merito, Cristina Rossi, Lucia Piscitello.

Cases:

- Mozilla/Apache case studies, at http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap10.pdf

- Microsoft shared source, http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262562278chap17.pdf