Property in Urban Commons

(from Vocabulary of Commons, article 42)

by Bhuvaneswari Raman

Property in urban commons

Contested spaces and embedded claims

Urban commons are defined as a form of new common and encompass a wide variety of territorial and social common pool resources including, streets, public roads, recreation areas (parks and lakes), networked infrastructure, markets and communities (Bravo & de Moor, 2008; Frischmann, 2005, 2007; Hess 2008). These spaces are coming under increased contestations in contemporary cities.

Conflict over the use of streets and open spaces is a common phenomenon that we witness in Indian cities as elsewhere.[1] Diverse groups of poor, among others, rely upon territorial commons including streets and a variety of other public places for both productive and reproductive purposes. Although contestations over urban space have been covered extensively in the literature on street commerce, collective actions in cities, it is rarely viewed from the perspective of commons. Similarly, while there is a vast body of knowledge about the dynamics of commons in rural settings, very little is known about the politics surrounding the claims on urban commons (Blomley 2008). This chapter seeks to contribute towards this growing literature through a focus on the contestations that emerge in Indian cities to claim streets and open spaces and the practices surround the control of these spaces in everyday life.

Diverse range of themes is covered in the emerging literature on urban commons. Some of these themes are:

- Enclosure of public spaces and infrastructure (Ahlers 2010; Bollier 2003; Lee and Webster 2006; Low 2000).

- Management of networked infrastructure (Anand 2000; Ruet 2002; Linn 2007; McShane 2010).

- Commoning practices particularly the contestations between the state and the community (Assadourian 2003; Blomley 2008; Lee 1998; Rogers 1995; Rosin 1998) and the dynamics of commons particularly the use of streets, parks and parking spaces (Anjaria 2006; Epstein 2002; Kettles 2004).

- Local security (Jenny et.al 2007 quoted in Hess 2008).

These have enriched our understanding of trends towards enclosing common spaces and the management of infrastructure commons. With the exception of a few studies, many are based on contexts outside India. Moreover, the dynamics of the commons has predominantly been analysed using economic lens or institutionalism and rational choice theory (Blomley 2010). In contrast, this chapter focuses on the political dynamics underpinning the making of commons. It draws on the theoretical approaches of ‘practice–force field’ (Nuitjen 2003), with a focus on everyday practices around the use, and control, of territorial commons within a wider socio-political fabric (Nuitjen and Lorenzo 2006). The dynamics described suggests a need to review some of the prevailing assumptions about community and property relations in commons.

Commons is viewed by some scholars as an alternative paradigm to that of property (see Bandhopadhyay in this volume). In this view, the paradigm of commons is not the same as that of public, private or communal property. It implies an association between commons and open access to resources. This chapter does not reject the concept of property but suggests that controversies surrounding the conception of commons using the lens of property are linked to many complex and contradictory views of property (see Brenda von Beckmann et.al 2006; Mukhija 2005).

As Bromley (1992) points out the terms commons, property and property regimes varies in the literature and are very often collapsed into one category. Hence, it is useful to clarify the definitions. Commons are understood as resources shared by many users. Property is understood as social relations which define the ‘bundle of rights and obligations’ associating the property object (territory / land), relating to the claims of property holders (see also, Bromley, 1992, Blomley 2008, Benda Beckmann 2007). Property is associated with an ‘object’ or with a specific type of regime in the literature (Blomley 2008; Bromley 1992). As Bromley (1992) argues, ‘property is not an object’ nor is it a specific type of regime. Resources may be controlled by the private, collective or the state. It is critical to understand that the claims of competing agents is on the property in commons i.e., bundle of rights and obligations to use streets or other types of public spaces and not the object of property (streets or parks). Thus, property in commons refers to a bundle of rights—collective or individual—relating to its shared interest and use. Property regimes ensure the compliance of the bundle of rights and obligations in the use of a variety of resources (Bromley 1992).

Claims on urban commons are contested as collectives seeking to establish their claims on streets and open spaces have diverse interests relating to the use and image of such territories.

Defining the boundaries of a community is intrinsic to the struggles for controlling commons. Community is not a homogenous entity with similar interests and consequently, claims to property in general and in territorial commons in particular, are reliant upon political process (Blomley 2008). This process is underpinned by the competition and contestations to shape property—specifically, ideas about the use of space, rights and obligations, social relations, social practices and regimes (Franz and Keebet Benda-Beckmann 2007). In situations where there is an intense completion to control resources, the dynamics turn over narrowing the definition of belonging (Peters 2006). Further, interests of groups seeking to control commons are diverse and those of members within a group may also change in time, which influences the fluidity of this politics. The boundaries of communities may shift due to shifting political alliances, changes in interest, and a shift in the wider political and economic fabric.

The politics at a particular time and space may open up opportunities to claim property in commons for some groups, while at the same time destabilising the claims of other groups. This dynamics is influenced by the wider political-economy and is characterised by flux and change. Here property is not absent but different types of opportunities and closures are generated for competing groups, depending on the politics at a particular time and space. The distinction between ‘property in commons’ from its regimes or compliance mechanisms (Bromley 1992) is crucial in this context. Hence, it is suggested that urban territorial commons are conceptualised as ‘force fields’, which is defined as “a field of power and struggles between different social actors with respect to dominance, contention and resistance as well as certain regulations and forms of ordering. These forms of ordering refer to ‘many rules of game’ experienced in everyday life but which are not formalised. Here the patterning of rules or organising practices are not necessarily a result of normative agreement but of the forces of play within the field” (Nutijen and Lorenzo 2006:219–220).

Claims on property in common territories can be legitimated in different ways, either socially or legally. For many groups, particularly poorer groups such as street traders and transport carriers who compete with relatively powerful residents and/or economic agents, social relations in everyday life is important in staking their claims. Their practices are based on a complex set of regulations and obligations embedded in a wider socio-political fabric. Another prevalent view is that commons are spaces that are (or to be) outside the influence of state/non-state and non-proprietary in nature. In contrast, studies on urban infrastructure commons (Anand 2000; McShane 2010) show the influence of state and non-state in the production and management of infrastructure commons. The political processes surrounding the claims to property in commons illustrates the complex alliances between different parts of the state and society.

A force field approach with its focus on ‘practices’ surrounding the use and claims on resources allow us to capture this dynamics. Conceptualising property in commons via a force field approach is also useful to conceptualise property relations in commons. Bromley (1992) differentiates between four types of property regimes—namely state, private, common, and open access. Streets and public spaces in cities are not open access territories as a group controlling a space seek to exclude others from its use. Controlling groups build enclosures to protect their claims. The bundle of rights and obligations of competing groups as well as those within each group are clearly defined, though these may not be easily visible. Rights of members to use this space are closely related to obligations towards the groups in terms of solidarity in everyday life. Neither can they be accurately described as common property regimes. A closer look at the dynamics shows that property relations in commons are much more characterised by flux and change. Community boundaries are shifting and the bundles of rights and obligations are continuously renegotiated between groups and within a group. A practice-force field approach (Nuitjen 2003) allows us to conceptualise this fluid and complex dynamics and allows us to assess the relative power and influence of different kinds of socio-political networks, their influence on the law and the state.

This chapter is organised in six sections. The first explores the dynamics of contestations over common territories in Indian cities drawing on the force-field approach. It engages critically with the notions of community and their interest in controlling the commons. Focussing on the ways in which different groups attempt to control urban streets, the following section lays out competing logics, perceptions about rightful claims and interests at work. The section ‘discursive everyday practices’ elaborates on the process by which communities establish their claims on commons. It illustrates embeddedness of claims of many, particularly poorer groups, in everyday life and their underpinning property relations. Drawing on the experience of small traders, this section shows the fluid politics of claiming property in streets and public spaces. This politics is characterised by a diversity of strategies, flexible alliances between competing agents with various scales of state. Further it illustrates societal embeddedness of claims and the ways in which agents’ embeddedness in different locales affect the claims of different groups. Focussing on property in territories is a useful way to understand the inter-related influence of ideas, practices, social relations and law in practice on the dynamics of urban commons. The property regimes in urban territorial commons are described in the next section.

The final section ‘the political praxis of commons’ concludes with a discussion on the political opportunities opened by the commons concept to strengthen the claims on cities, of relatively less powerful economic and social groups.

The force field of commons: Communities, conflicting interests and logics

This section describes the contestations that emerge in cities to claim territorial commons, specifically the streets and open spaces. It illustrates that commons is a field where differing interests of social actors and groups, their associated logics, and power and resistance are at play. These struggles are about defining or, more accurately, limiting the boundaries of communities. Their outcomes are influenced by the ‘forces of play within the field’ (Nutijen and Lorenzo 2006:220).

Blomley’s (2008) article on ‘enclosure, common rights and property of the poor’ maps the dynamics of contestations surrounding urban commons, between a private developer, state and community. The private property rights of the developer worked to the disadvantage of the poor. However, in subverting the workings of private property, affected groups invoked community claims on property in land. The counter posing of property claims that are collective in nature is a key weapon for affected groups to frame their demand in this conflict. The interest is ‘collective one’ and so is the claim of the ‘collective’ (community) to the contested resource. Here, collective interest and community are counter posed against private property interests. The community appears to be a homogenous space in this description.

Whose commons and which community?

Another phenomenon increasingly witnessed in urban areas is the contestation between collectives and groups to establish their claims on property in commons. A specific feature of urban areas is characterised by diversity. What is assumed as ‘local’ or ‘community’, is often a space where divergent and at times contradictory interests may coexist or collide. Box 1 below summarises an ongoing conflict in my residential neighbourhood. The setting of this conflict is an old neighbourhood named T Nagar in South Chennai, characterised by mixed land use. The conflict over the use of streets in this setting revolves around the conflicting interest between residents, traders and transport users.

Box 1: Reclaiming the streetTheyagaraja Nagar in South Chennai, is a locality with a mixed land use, characterised by dense commercial activity interlaced with residences. Currently, one of the major commercial nodes in the city, and its history goes back to the early 1920s. Residential layouts characterised by individual bungalows dominated the landscape until the late1980s. The plots then were owned predominantly by dominant caste/class professionals. Many of these plots are converted into multi-storeyed apartments. More recently, properties were taken over for business purposes. The expansion of commerce, together with densification of residential property, has contributed to a dense congregation in many streets of this neighbourhood. While initially the business was owned by members of the Muslim community, traders from a Hindu sub-caste currently dominate trade in this area.

The dense congregation in this locality together with commerce makes this setting an ideal location for poorer groups both to find employment and/or to consume services. Street traders and transport carriers—autorickshaw drivers—jostle with clientele of various commercial establishments and residents to occupy every inch of space in this locality. Transport carriers occupy the entrance to streets and share their space along with customers of various business premises. With the increase in residential population together with the expansion of trade activities of property owners—residents or business—spilled their activities onto the street. They compete with transport carriers and visiting customers to park their vehicles.

On 26 September 2010, some residents living on M street took to the streets. The incident was reported in a major English daily in the city. To quote a newspaper, ‘The group blocked the road and sat down waving placards reading, “Don’t convert our street into a urinal”, “Re-lay proper roads”, “Don’t dump garbage on our street” and “Remove unauthorised vehicles from the street”’ (Deccan Chronicle, 27 September 2010). After protesting for an hour, the group met with the assistant commissioner of police (ACP). Since then they have been meeting the deputy commissioner of police regularly. Residents mobilised an old association.

Following the meetings, there was an eviction drive which targeted the autorickshaw stands on either entrance to the streets. The removal of the right to park in these spaces was signified by announcements on the wall. Traffic flow through the street was also curtailed. Autorickshaw drivers affected by the moves appealed to the local political leader. They also aligned with the traffic police to monitor the movement of vehicles through the street. Differentiation between ‘insiders’—stand auto drivers— and ‘outsiders’ appeared overnight.

During the third meeting held on 8 November 2010, the ACP has promised again to remove ‘unauthorised’ parking spaces and to discipline ‘unauthorised’ autorickshaw drivers at one end of the street. On the other hand, the traffic cop who attended the meeting pointed out that residents also park on both sides of the road and implied that a part of the parking problem stems from their actions. The conflict is far from over...

Contests over commons operate at different levels in the street. At one level, is the conflict described above, which is perhaps a common phenomenon that is visible in busy neighbourhoods in many cities. Interests of different collectives congregating within urban streets, let alone neighbourhoods, differ. It manifests as conflicts over the use of streets for productive use, or as spaces of circulation as well as the density of congregation. There are contrasting ideas on the aesthetics of immediate environment. Their images of place making and their interests in controlling commons may thus vary.

Residents perceived street spaces as their ‘lost’ commons that needs to be reclaimed from ‘illegal’ encroachers. They argued that their movements are hindered by ‘outsiders’—the customers of retail business and transport carriers—who have appropriated ‘their’ streets. Their rationale is that by virtue of their claims on private property in the street, they are the ‘rightful’ claimant to spaces in front of their properties, i.e., streets. The same logic of property ownership was extended by business owners, for whom parking for their customers is a duty of the state. Thus, their movements—both human and vehicular—are to be prioritised. The transport carriers argued that their claims to space are based on occupancy and everyday use for over three decades, and that they depend on this space for their livelihoods.

Perhaps, a more subtle, invisible dynamic was at work which catalysed mobilisation of a group of residents in the street. This relates to perceptions about takeover of their ‘locality’ by other communities whom they feared and described as ‘predators’. Everyday conversations with residents, most of whom are Hindus revolved around the quiet construction of a mosque and individual investment in properties by members of the Muslim community. The ‘unauthorised’ parking refers to the parking space in front of the mosque and clientele’s vehicles parked in the street. According to members of the Muslim community, they were the ‘original residents’ and ‘business agents’ in the neighbourhood and that they are reclaiming their lost space. The group’s description of the occupancy of streets by autorickshaw drivers is not so much about parking but about their ‘undisciplined’ behaviour towards the residents. This got translated into authorised and unauthorised parking. Of the two stands in the street, one was targeted.

In a city laced with anti-Brahmin caste ideology and dominance of perceived anti-Brahmin political parties, middle and upper class residents perceived themselves as victims of an apathetic bureaucracy, who pay no attention to their plight. Although social ‘identity’ of groups and perceptions about their situation in wider politics influenced the politics in the neighbourhood, these issues are often pushed to the subterranean. Residents from dominant castes frame their claims to commons under the rubric of the ‘rule of law’. Their struggles to claim commons are thus linked to claiming their lost territory, disciplining the unruly actors.

While the traders, street traders and autorickshaw drivers seek density and diversity of congregation for their trade, residents’ interests are to erase the density of activities on the street for a variety of movements. To many autorickshaw drivers, the actions of the resident association are driven by caste and class bias and view it is an attack on their livelihoods. Autorickshaw drivers mentioned in a conversation with the author that they belonged to the street, and identified themselves as ‘stand autos’, meaning they ‘belonged’ to the autorickshaw stands at both ends of the street. They too have a claim on the street but not the outside autos, who were the trouble makers. Autorickshaw drivers at both end of the street identify themselves as two groups. One of the groups actively assisted the traffic police in monitoring the ‘outside’ vehicles. The differing interests and competition sets in process additional enclosures between groups and consequently there is a struggle to be included as insiders. Both groups’ alliances with residents differ. One group maintains relations with some residents who are their clientele. However, both groups rely on their loyalty to political parties and channel their demands relating to the claims on streets via the political parties. It also spilled onto the struggle to be identified as members of the community. Similarly, other forms of enclosures have been erected by residents. Landscaping of public pathways and open space immediately in front of their plots is a common tactic adopted by residents. Contestations over parks have played out when residents of a locality seek to create enclosures restricting the groups that can use and their terms of use.

To what extent do the dynamics of urban commons fit the template provided for commons in the literature? Who constitutes the community in the case described above? Commons are described as resources held by a community of inter-dependent users who exclude outsiders and regulate internal use by community members (Blomley, 2008; Ostrom, 1990). Blomley argues (2008:319) ‘the commons depends upon and are produced in relation to a constitutive outside... then it is also imperative that we consider the dynamics of enclosures’. Competing social actors described in this section too cooperated with one another to exclude others from the use of resources. The communities described above are not unified group with similar interest in contesting the forces of privatisation or interested in a harmonious management of commons unlike in many studies on commons (see Blomley 2008; Lee 2006). The struggles over urban territorial commons are not only about confronting the forces of privatisation but more related to intra-community conflicts. Threats to groups’ claims to commons can emerge from other groups congregating in a territory. This stems from the specificity of urban commons where agents with diverse and often contradictory interests congregate in a territory.

Thus, urban territorial commons are spaces where different groups with diverse interests compete to establish their claims to use, or to control the use, of commons. Not only do interests between groups vary but also among members of a group. For example, street traders while sharing a common interest in controlling public spaces for their activity may have different visions of how these settings are to be shaped depending on the type, scale and social identity (Raman 2010). It affects the manner in which community boundaries are negotiated. The definition of community is fluid in the contestations described in box 1. Consequently, urban territorial commons can be described as ‘force fields’ of power and struggles between different social actors and its outcome is shaped by the politics in a particular place and time.

Embedded claims and the politics of claiming urban commons

The making of commons in many of our cities is reliant upon an intense political process and claims on it are staked on moral, legal, and political basis. This section illustrates the discursive aspect of this politics, drawing on everyday practices among street traders to establish claims to streets and open spaces in an Indian city.

It shows that communities have to continuously negotiate their claims to urban territorial commons (Raman 2010).

Discursive everyday practices surrounding claims

The following example illustrates the experience of street traders in establishing their claims on property in land in a peripheral locality in Bangalore. Traders here occupy a specific type of land allotted for ‘markets’ or locally known as ‘santhes’. ‘Santhes’ can be described as a form of communal property, which was allotted for village markets. The practices of allocating village commons for santhes were traced to pre-colonial times, and which was continued by post colonial governments. With the annexation of these spaces into urban areas together with the political-economy of real estate markets in contemporary times, different layers of conflicts have emerged over claims to santhe spaces. At one level, there is an ongoing conflict between farmers, various groups of traders, non-state agents and the state relating to the allocation of specific location and area to different groups. Unlike traders on other types of public land, the local state and residents perceive the legitimate use of santhes for trade but the conflict is over the definition of ‘rightful claimants’. At another level, there is a demand to evict traders occupying santhe land in order to reclaim land for other ‘profitable’ uses including the sale of land or allocation to private spaces.

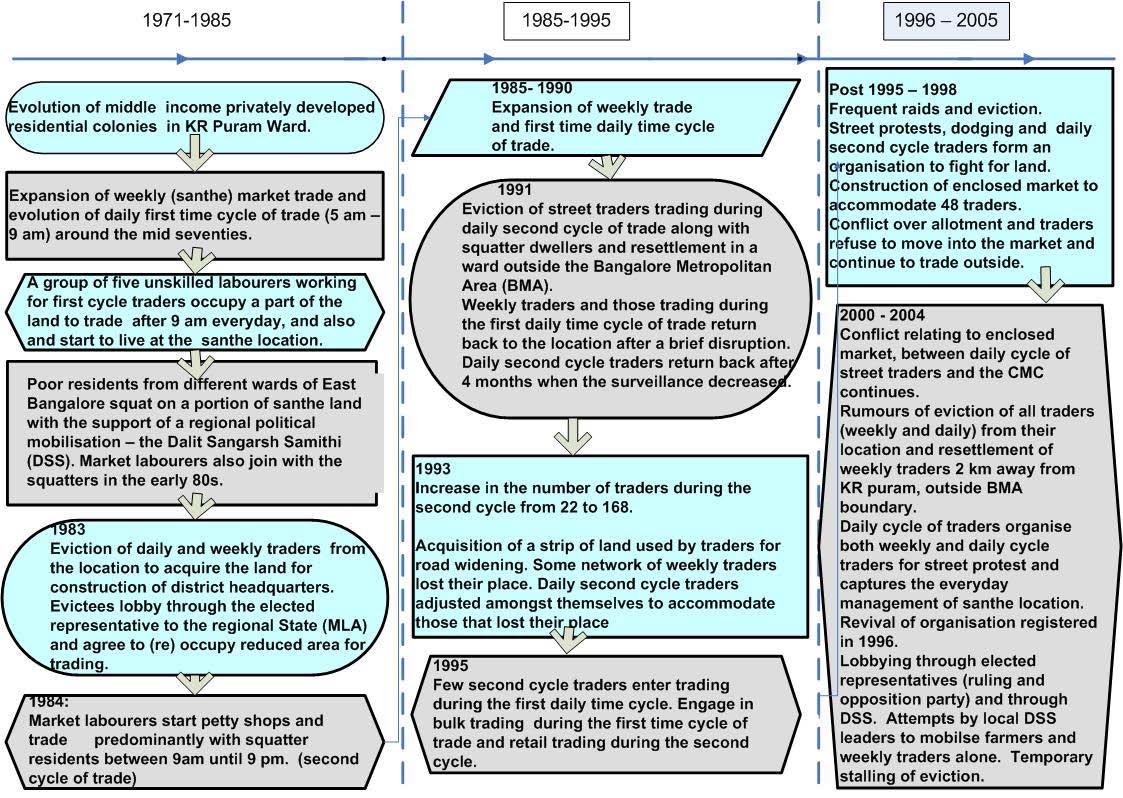

Figure 1 traces the evolution and development of trade in a santhe in the peripheral locality in Bengaluru metropolis in India. Although santhes existed prior to 1971, we start the narrative from 1971, when the locality started to get urbanised. What started as a small market organised on one day of a week, predominantly by farmers, developed as one of the main distribution nodes in the city. At present, trading is organised in three cycles and in different scales.

When the market started to develop, members of traders’ families from the surrounding village occupied spaces in the santhe. Even today, each of these groups defines their identity according to the place of residence. They travel to santhes as a group and socialise predominantly with their group at the santhe location. Many of these traders initially traded during the early mornings for a limited time until the 1980s. In the early 1980s (column A), a local political organisation organised poorer households from a socially and economically disadvantaged community, i.e., the Dalits to occupy vacant land adjoining the santhe. The santhe was located in vacant land, owned by the state. Unlike markets on streets in other parts of Bengaluru, large tracts of land are allotted for santhes. There is an ambiguity over the boundaries of santhes.

Availability of space and perception of land as public or government land were seized by the Dalit organisation to capture the place for its constituency. Various other groups too made use of the opportunity that opens when any particular group occupy a space. Market labourers who used to work for traders in the early morning erected rudimentary structures for their residence and also captured land for their friends and relatives. The local state evicted both traders and squatters in 1983 but both groups reoccupied the space with the help of the same political organisation, albeit on a reduced area. Subsequently, land was acquired for the construction of a district court and the offices of the district administration. This resulted in displacement of a group of traders and reorganisation of claims between traders within the santhe. Following this event, the occupiers consolidated their structures. Those with plots along the main thoroughfare constructed temporary sheds for their own business or for renting it out as petty shops. Market labourers occupied the vacant land adjoining the petty shop and traded everyday for a limited time in the early mornings and in the late evenings.

Between 1985 and 1995, as can be seen in the above figure, the number of traders in the two cycles increased rapidly and second cycle traders consolidated their business. Traders were evicted in 1991 along with squatter dwellers and were resettled in an outlying village, 12 kms away from the santhe location. However, many market labourer-traders returned and occupied the place vacated by squatters and supported their networks to enter trade in the agglomeration. Thus, by 1993, the number of traders trading during the second cycle increased from Figure 1[2] Trajectory of Claiming Common Land for Trade 27922 to 165 and more than 500[3] in the first cycle. Some second cycle traders expanded their business through entering different cycles.

Post 1995 (Column C), increase in the number of traders and the concomitant competition for space together with the high real estate value of santhe land generated several conflicts among street traders and between street traders and the City Municipal Corporation (CMC). Rumours of eviction of both weekly and daily traders started to circulate since early 2001. While the CMC’s commissioner was willing to find an alternative location for weekly traders, he argued that the daily traders’ demand for a place is unreasonable as they refuse to move into an enclosed market constructed for them on santhe land. Daily traders on the other hand contend that they moved out of the market to occupy a smaller area since not all of them can be accommodated, the move inside increased their cost of trade and that the design was faulty. Reduction in the area led to conflicts between vegetable traders and fruit traders. Pressure on daily traders to move inside the complex increased and weekly traders are still negotiating for relocation within 5km along a public thoroughfare. In 2004, a group of youth traders involved in both trading cycles revived an old organisation, mobilised farmers and traders across different time-cycles, tapping the grievances relating to location and the daily fee levied to trade on santhe land and organised a traffic blockade. The MLA intervened and the santhe land administration was handed over to the youth leaders, who view this as an opportunity to strengthen their ties with the CMC’s senior bureaucrats to lobby against the eviction. Although street traders managed to stall the eviction until the end of 2010, the conflict is far from over.

As the above experience of traders show, the pressure of globalisation together with the changes in politics, particularly the demand from a section of middle and upper class citizens, has generated additional pressures on erasing traders’ claims on property in santhes. The outcome of these conflicts is shaped by political alliances—including but not restricted to political parties, non-party political mobilisations and other types of local agents. Social relations between these agents and santhe traders have a significant influence on the outcome of these conflicts. The location of santhes and the processes of claiming it cannot be located entirely outside the state. The high real estate value in the peripheries of the city set in process contestations over the ‘perceived’ state ownership of the santhe land. Private agents claimed ownership to it. Competition to control productive locations within the santhe influenced the flexible alliances between different agents and varied groupings, each drawing on different sources in justifying their claims. However, in countering the threat from outside, competing groups of traders aligned to counter what they perceived as an ‘external threat’. Relationship between these groups is shaped by the dialectics of ‘cooperative conflicts’. A focus on everyday practices at the santhe is useful to unpack this dynamics.

Embedded claims

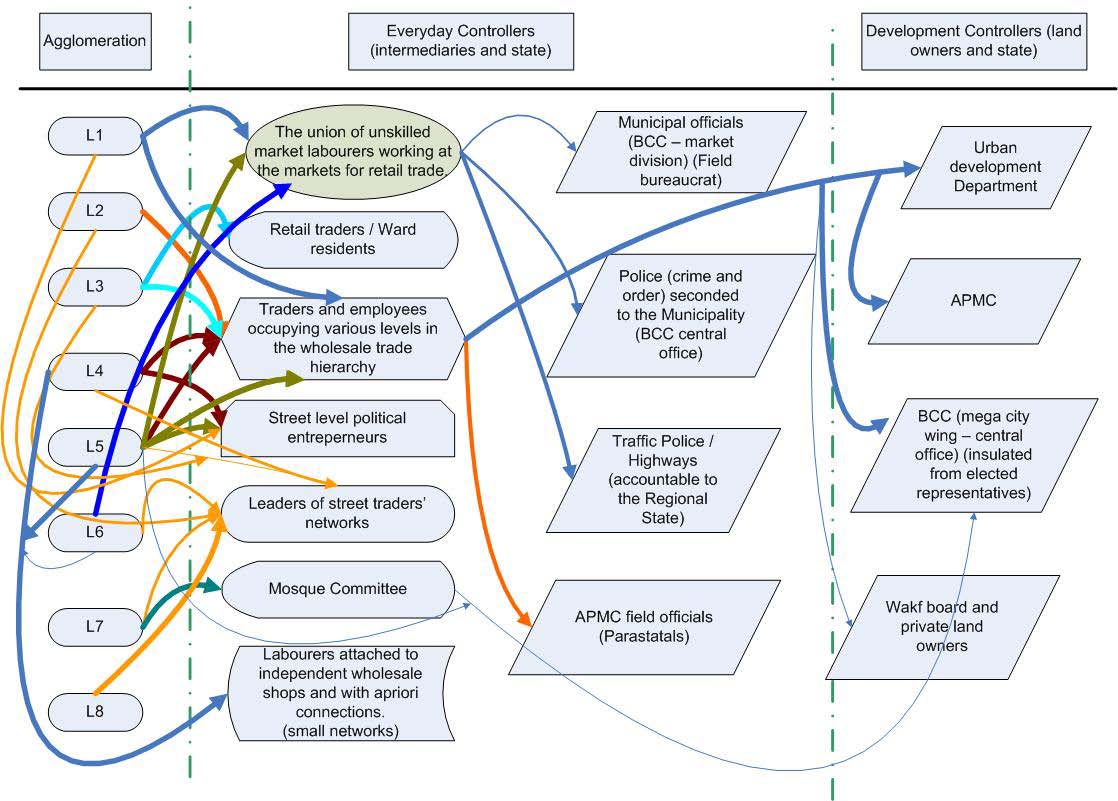

Property in common spaces is influenced by diverse range of agents, one of which is the state. A study[4] on street traders in Bangalore found that there is a ‘plurality of control’ (Razzaz 1994), in relation to the use of places in everyday life in each ward. Fig.2, illustrates the various controllers found in a centre city locality in Bengaluru, and their influence in terms of regulating the everyday use and development of public spaces at different locations.

As can be inferred from the figure, controllers include agents embedded in the everyday state (Fuller and Harris 2001), other users, land owners, and state institutions who intervene in land development at certain moments. Their characteristics and their influence over regulating claims among different users differed across place and time. They derive their power to influence everyday use of space from a variety of sources including historical conventions, law and contemporary politics. In establishing their claims on property in streets and other types of public places, street traders entered into negotiation not only amongst themselves but also with other agents in the city.

In staking their claims on commons, agents such as santhe traders described above, resort to a diverse range of collective strategies including spontaneous protests, negotiations through networks and organised efforts. The process is discursive and occurs in a variety of political and social spaces (Raman 2010). Here, competing agents engage with different parts and scales of the state (Benjamin 2000; Raman 2008) and also form flexible alliances with one another. In the box described above, residents predominantly engaged with bureaucrats, while their opponents relied on the political connections. Transport carriers affected by the conflict, as other associations elsewhere, maintain close links with party politics.

Such alliances may change during the course of the conflict depending on the interests and changing political dynamics (Raman 2010). For example, in a centre city locality in Chennai in India, retail traders who supported the street traders claim to property in an open space in the locality during a conflict between the latter, a property owner and traffic police, to locate in another business district at one time, shifted their alliance following a murder of a member of their group. While on an earlier occasion traders argued that presence of street traders was important for their business and security, they subsequently invoked security as their rationale for demanding the removal of street traders.[6]

Social networks provided the organisational context for these negotiations. The high level of competition for places, and surveillance by other street traders and users, compelled street traders to function as a group. The relationship between everyday controllers and the state influenced the ability to claim various economic and political spaces. This in turn is mediated by the ways in which groups are embedded in the political and economic processes specific to the locality influences the interdependencies and transactions among these agents. It is a point we return to in the next section on strategies to strengthen rights on urban commons.

Changes in institutional arrangements for urban governance together with new laws have altered the dynamics of this conflict. With globalisation and the increased real estate value, the state sought to evict traders. Where evictions were subverted, they adopted a strategy of acquiring a small area of land in stages.

Property relations in streets and public spaces

The dynamics of territorial commons—in terms of its control and internal rules for its use—share many similarities with force fields with a great diversity of practices. These are not open access territories but places where claims in property are regulated. Scholars of common property regimes note the existence of internal rules and principles that govern access to and control of resources and broader principle of risk pooling (Oakerson 1992; Bromley 1992). Rights and obligations in property are clearly defined in common property regimes, where it departs from open access. Boundaries of the group are clearly defined. There is a socially sanctioned ability to exclude certain users and those in control can force others to go elsewhere. The need to counter competition over space from outside a group compels members of a group not only to cooperate with one another. However, they may restrict the membership to each group but may enter into negotiation with other groups. This dynamics is shaped by the incompleteness of property claims in any resource as the experience of santhe traders show (see also fig 1). Therefore any claim is open to contestation by members within and outside the group. This dialectic may erode the boundaries of enclosures between groups and the tendencies of free riding among members of a group.[7]

Street traders and transport carriers control public spaces as a group, both at the time of establishing their claims in property to that space and subsequently, to protect their claims (Raman 2010). To these occupational groups, operating as a group is critical to claim and control property in public spaces. Consequently, members of a group ‘mutually adjust’ (Razzaz 1994) with one another and also, cement their relationship with other competing users.

As the narrative in box 1 indicates, autorickshaw drivers in cities make a distinction between ‘stand autos’, and ‘strangers’/ ‘outsider’. The distinction made not only refers to perception of claim relating to property in streets, or about control of the physical space but is also related to economic and political opportunities. Conflicts between those identifying as ‘stand’ autorickshaw drivers and ‘outsiders’ is a common phenomenon we witness in everyday life. These conflicts are as much about claiming parking spaces and capture of clients (or markets). Membership in these group is based on willingness to cooperate with the groups in terms of pricing, sharing clientele, and participating in political or social activities. In turn, members expect the group and the group leader to support them in times of individual or collective crisis.

The threat of losing their property in space motivates autorickshaw drivers to regulate the ways in which they use space in everyday life and to restrict the number of vehicles. We return to the conflict described in box 1. Following the conflict, policing of streets increased. However, different patterns of alliances emerged. Those who identified themselves as ‘stand autos’ aligned with everyday state agents (Fuller and Harris 2001) and are active in regulating the movement of traffic, particularly autorickshaws, in the streets. Many of them are also connected to the residents because of everyday interaction. Retailers agreed to move back their activities. These crisis are temporal nodes where tacit norms relating to the use of street and claims are renegotiated.

Under conditions of resource scarcity tendencies to erect enclosures differ. While the normal tendency is to erect enclosures, interdependencies between groups may limit such tendencies. Traders belonging to different groups closely guard the property in relation to the extent of physical territories. That does not preclude a group to enter into sharing arrangements with other groups. For example, property in streets is distributed between different groups of traders in commercial nodes including the city centre and periphery, characterised by different types of trade. The centre city locality in Bangalore is influenced by economic cycles. Trade on public places and streets is organised in different cycles. Here groups enter into negotiation with one another. Group identity is defined by their place of origin or the type of trade. Support to groups is based on future expectations at another place, while in times of non-scarcity, there were less hesitancy to erect enclosures, these got more defined as space became scarce and accommodating more traders meant loss of trade.

Within common property regimes, property in territories is not compatible with individual use of one or another segment of a resource (Bromley 1992). Their functioning shares several similarities with state or private property regimes. Although claims to property in each street are negotiated predominantly in groups, members of a group have evolved specific arrangements to share their spots with their close ties (Raman 2010). Each trader is allowed to occupy a space of 1.5mx1m or 1mx1m at KR Market; 1mx2m in the inner periphery; and 1mx1m to a maximum of 1.5mx 2m in the outer peripheral wards. In return, group members are expected to participate in social functions and in political activities.

There is also a market for the sale and purchase of these spots. Renting, leasing, and sale of street trading spots were found in different contexts (Raman 2010; Brown 2005). While both buyers and sellers have an obligation to inform the group about the transactions, the buyer has to ensure that potential sellers will cooperate with the rest of the group (Raman 2010). The manner in which these transactions are protected are not very different from the processes observed in private property regimes. These transactions are mediated by social networks and there are contractual obligations both on the part of buyers and sellers. Sellers have to ensure the buyer’s—a new trader’s—stability at the agglomeration. A similar contractual obligation has been observed in the land transaction processes related to private plots for housing (Razzaz 1994; Nkurunziza 2005). Another example is the ways in which people transact in relocation colonies in Chennai. A study of the relocation colonies in Chennai city (Raman forthcoming) showed that although residents register the sale of individual housing units, they rely on community members to protect their transactions. Buyers therefore invest in mobilising influential members of the community.

Thus, unlike in open access, property in streets and other types of public spaces are governed by social regulations. Moreover, property in common territories may comprise of different bundles of rights and obligations (Peter 2006), which are both de-facto and de-jure (Blomley 2008; Feeny et al. 1990; Rose 1998). For example, the land tenure and regulation of common territories occupied by groups categorised under the label ‘street traders’ differ. In Bangalore, street traders occupied a specific type of land referred to locally as the ‘santhes’, state owned or regulated spaces and private land (Raman 2010). Moreover, tenure forms in which trading spots are held by members of a group may also vary. Groups may form organisations or remain as a loose alliance, where social networks mediate the transactions within and between groups (Singermen, 1995; Raman 2010). All these aspects influence the different constellations of property in urban commons. Thus, these resources are not only governed by common property regimes but its forms also differ.

The political praxis of commons

It is suggested conceptualising territorial commons as a ‘force–field’ opens up a useful tactical space to mobilise commons on behalf of those groups who are disadvantaged by the ideologies and practices of modernist planning.

The project of making cities attractive for global investments has resulted in a variety of new forms of enclosure. Various categories of land collapsed under the rubric of public land are either being privatised or acquired for implementation of urban renewal programmes, allocation of designated territories for corporate economies through the creation of SEZ and IT corridors and gated communities. Here, planning goals are oriented primarily to regulate the interests of globally connected economies, much to the detriment of small economies and communities that depend upon them.

Modernist planning ideologies not only prioritise private property rights but it also influences in subtle ways ideas about commons and the rightful claimants to spaces like streets and parks in everyday life. Claims of relatively weaker economic groups such as street vendors and transport carriers continue to be interpreted through the lens of illegal/ legal or informal/ formal, which in turn affirms the claims of some groups—often the property owners—on streets and other types of common land. It is in this light commons viewed as force-fields (Nuitjens 2003), provides a useful vocabulary to reframe these contests and to create spaces for strengthening the bargaining power of groups whose claims are eschewed at present.

Nevertheless, care should be taken not to fall into the trap of situating ‘commons’ within the framework of master planning and rehearsing the argument for individualised rights. The language of rights translates into demand for legal rights, which further gets reduced to identifying individualised rights to property in commons. An example is the current interpretation of hawking zones and the demand for issuing individual licences. Driven by the logic of inclusion, the language of collective rights and claims is missing in this debate. Paradoxically, it is here that the demands of interests seeking to protect common and globally connected economies meet in terms of defining individual rights to a specific spot of land or location.

In enhancing the bargaining power of relatively weaker groups, some scholars associate commons with movements as it provides a basis for connecting disparate interests and conflicts opposed to globalisation (Hardt and Negri 2004) and to counter these ‘new waves of enclosures’ (Harvey 2003). Although, everyday politics and ‘local’ space influences significantly the claims on commons of different groups, it is often neglected. Movements are prioritised as the only way out to reclaim the commons.

As the conflicts elaborated in this section show, commons are turbulent spaces comprising of conflicting yet shifting interests and flexible alliances. The outcome of occupancy politics (Benjamin 2008) is influenced by both conflicts and negotiations that are mediated by everyday relations (Raman 2010). Groups competing for commons may form different alliances with what is posed as ‘corporate economies’. For example, interests of residents in an upper income locality in Bengaluru and environmentalists to reclaim ‘lakes’ may contradict with the interests of poorer groups among others depending on it for their housing or livelihoods. Local space in this context refers to both the political space and place (i.e. neighbourhood) where mediation of these conflicts occurs.

Demands and strategies for protecting poorer groups’ interests in commons need to be situated in a political-economic context, where there is a demand from privatised interests—specifically, large developers and corporate economic—for identifying and marking individual interest to a plot of land. What is also missed out from this perspective of commons as a movement are the strategies of the state in creating these new enclosures. These are underpinned by new institutional and legal mechanisms that cannot be countered easily through collective action at any particular scale.

The notion of force-fields is based on the prevalence of a great diversity of strategies—some of which are organised but many are practices that are invisible quiet, strategies enacted through ‘networks of everyday relations’ (Singermen 1995). These negotiations and subversions relating to claims to use commons or to control its use happens in everyday practices, wherein the role of the everyday state (Fuller and Harris 2001) or Benjamin’s (1996) ‘porous bureaucracy’ and porous legality (Liang 2005) are important.

The point is that any strategy should support the creation of multiple weapons that relatively weaker groups can draw upon to strengthen their claims on commons. It is in this context, what Massey (1998) terms as the political place of local/localities becomes significant. Implicated in this issue are both the ideology and practice of urban planning. Rather than affirming existing practices and the present ideology of planning, commons can serve as an analytical concept to reframe urban contestations.

Conclusion

This chapter explored the political dynamics surrounding the claims on, and control of, property in commons. It illustrated the contested nature of claims on commons and further suggested that a focus on property is useful to unpack the variety of agents holding rights on commons. The politics of urban commons is an aspect about which there is limited documentation (Johnson 2004; Blomley 2008). Exploring the contestations to claims on commons, the first section highlighted the fluid definition of community and argued for conceptualising commoning processes as a political process. Claims on commons are an outcome of contestations between different social and economic groups in cities to shape property relations and regimes. Contestations over city spaces in contemporary times is not only related to the dynamics of controlling resources including urban space either collectively (public/community) or individually but also about defining the boundaries of community.

Commoning practices documented and the available literature throw light on organised actions by a community (Lee and Webster 2006; Anand 2000). In contrast, this chapter elaborated on the ways in which everyday relations influences the politics of claiming. It illustrated the diversity of strategies used by members of a group to claim their property. It showed the flexible alliances and the fact that the community may shift their interests over time, and described the regimes for governing property in streets and other common spaces. Finally, it was argued that the political potential of the commons vocabulary in the urban context lies in the possibility to of a new framework to re-conceptualise city spaces, beyond the narrow frame of private property.

References

Ahlers, R. 2010. Fixing and Nixing: The Politics of Water Privatization. Review of Radical Political Economics, 42, 213-230.

Anand, P. B. 2000. Co-operation and the Urban Environment: An Exploration. Journal of Development Studies, 36, 30–58.

Anjaria, J. S. 2006. Street Hawkers and Public Space in Mumbai. Economic and Political Weekly 41, 2140–2146.

Arvanitakis, J. 2006. Education as Commons: Or Why We Should all Share in the Picnic of Knowledge. Available: https://cpd.org.au/2006/04/education-as-a-commons-why-we-should-all-share-in-the-picnic-of-knowledge/

Assadourian, E. 2003. Cultivating the Butterfly Effect: The Growing Value of Gardens. World Watch, 16, 28–35.

Benda-Beckmann, F. V. & Benda-Beckmann, K. V. 2006. How Communal is Communal? Whose Communal is It? In: Benda-Beckmann, F. V., Benda-Beckmann, K. V. & Wiber, M. G. (eds.) Changing Properties of Property. New York Berghan Books.

Benjamin, S. 2008. Occupancy Urbanism: Radicalizing Politics and Economy beyond Policy and Programs. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research (IJURR) 32(3):719-729.

Benjamin, S. 2000. Governance, Economic Settings and Poverty in Bangalore, India. Environment and Urbanization Vol. 12 No.1 (April):35-56.

Benjamin, S. 1996. Neighbourhood as Factory: The influence of land development and civic politics on an industrial cluster in Delhi, India MIT, Cambridge Massachusetts PhD dissertation.

Blomley, N. 2007. Making Private Property: Enclosure, Common Right and the Work of Hedges. Rural History, 18, 1–21.

Blomley, N. 2008. Enclosure, Common Right and the Property of the Poor. Social & Legal Studies 17, 311–331.

Bollier, D. 2003. Silent Theft—The Private Plunder of Our Common Wealth. London and New York: Routledge.

Bravo, G. & Moor, T. D. 2008. The Commons in Europe—from past to future International Journal of the Commons, 2, 155–161.

Bromley 1992. The Commons, Common Property and Environmental Policy. Environmental and Resource Economics 2, 1-17.

Brown, A. 2005. Contested Space, Public Space and Sustainable Livelihoods. A paper presented at ‘Connecting People and Places: Challenges and Opportunities for Development’, Development Studies Association Annual Conference Open University, Milton Keynes. Corbridge, S. 2005. Seeing the state : governance and governmentality in India, Cambridge ; New York, Cambridge University Press.

Epstein, R. A. 2002. The Allocation of the Commons: Parking on Public Roads. Journal of Legal Studies, 31, S515–S544.

Feeney, D. F., Berkes, B. J. & Acheson, J. M. 1990. The Tragedy of the Commons: Twenty Two Years Later Human Ecology, 18, 1–19.

Frischmann, B. M. 2005. Infrastructure Commons Michigan State Law Review, 89, 121–136.

Frischmann, B. M. 2007. Infrastructure Commons in Economic Perspective. First Monday [Online], 12. Available: http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1901 Fuller, C. J. & Hariss, J. 2001. For an anthropology of Indian State. In: Fuller, C. J. & Veronique, B. (eds.) The Everyday State and Society in Modern India. London: Hurst & Company.

Garett, H. 1968. The Tragedy of Commons. Science, 162, 1243–1248.

Hess, C. 2008. Mapping the New Commons Governing Shared Resources: Connecting Local Experiences to Global Challenges. 12th Biennial Conference at the International Association for the Study of Commons. University of Gloucestershire, Chelternham.

Jenny, A, Fuentes, F. H. & Mosler, H.J. 2007. Psychological Factors Determining Individual Compliance with Rules for Common Pool Resource Management: The Case of a Cuban Community Sharing a Solar Energy System Human Ecology, 35, 239-250.

Johnson, C. 2004. Uncommon Ground: The “Poverty of History” in Common Property Discourse Development and Change., 35, 407–33.

Kettles, G. W. 2004. Regulating Vending in the Sidewalk Commons. Temple Law Review, 77, 1–46.

Lee, I.–J. 1998. Collective Action and Institutions in Self-Governing Residential Communities in Seoul, Korea. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Southern California.

Lee, S. & Webster, C. 2006. Enclosure of the Urban Commons GeoJournal 66, 27–42.

Liang, L. 2005. Porous Legalities and Avenues of Participation. In: Sarai Reader 2005: Bare Acts. http://archive.sarai.net/files/original/8d57bfa1bcb57c80a7af903363c07282.pdf (accessed 2 January 2017)

Linn, K. 2007. Building Commons and Community, New York, New Village Press.

Low, S. M. 2000. On the Plaza: The Politics of Public Space and Culture, Austin, TX, University of Texas Press.

Massey, D. 1991. The political place of locality studies Environment and Planning A, 23, 267–281.

Massey, D. 1993. Power Geometry and a Progressive Sense of Place In: Bird, J., Curtis, B., Putnam, T., Robertson, G. & Tickner, L. (eds.) Mapping the Futures: Local Culture, Global Change. London: Routledge.

Mukhija, V. 2005. Collective Action and Property Rights: A Planner’s Critical Look at the Dogma of Private Property. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29, 972-983.

Nuijten, M. & Lorenzo, D. 2006. Moving Borders and Invisible Boundaries: A force field approach to property relations in the commons of a Mexican Ejido. In: Beckmann, F. V. B., Benda-Beckmann, K. V. & Wiber, M. (eds.) Changing Properties of Property New York Berghan Books.

Nuitjen, M. 2003. Power Community and the State; the Political Anthropology of Organization in Mexico, London Pluto Press.

Oakerson, R. J. 1992. Analyzing the Commons: A Framework In: (ed.), D. W. B. (ed.) Making the Commons Work: Theory, Practice, and Policy. San Francisco: San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action New York, Cambridge University Press.

Peters, P. E. 2006. Beyond Embeddedness: a Challenge Raised by a Comparison of Struggles Over Land in African and Post-Socialist Countries. In: Benda-Beckmann, F. V., Benda-Beckmann, K. V. & Wiber, M. G. (eds.) Changing Properties of Property. New York: Berghan Books.

Raman, B. 2010. Street traders, place and Politics: A case study of Bangalore. PhD Dissertation, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Raman, B. (Forthcoming). Relocation and Livelihoods: The Case of Chennai.

Razaaz, O. M. 1994. Contestation and Mutual Adjustment: The Process of Controlling Land in Yajouz, Jordan. Law & Society Review, 28, 7–39.

Rogers, N. B. 1995. Modern Commons: Place, Nature, and Revolution at the Strathcona Community Gardens Ph.D. Dissertation, Simon Fraser University.

Rose, C. 1998. The Several Futures of Property: Of Cyberspace and Folk Tales, Emission Trades and Ecosystems. Minnesota Law Review, 83.

Rosin, T. 1998. The Street as Public Commons: A Cross-Cultural Comparative Framework for Studying Waste and Traffic in India Crossing Boundaries. A paper presented at Crossing Boundaries: the Seventh Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property. Vancouver, British Columbia: IASC. http://hdl.handle.net/10535/1769 accessed on 18 November 2010.

Ruet, J. 2002. Water supply & sanitation as ‘Urban Commons’ in Indian Metropolis: How redefining State/Municipalities Relationships should combine global and local de-facto commoners In: A paper presented at the Ninth conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property held on June 17–21 2002 Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe. Singermen, D. 1995. Avenues of participation University of California press

Endnotes

- ↑ There exists a vast body of literature on contestations surrounding the use of public land and streets between diverse occupational groups such as street traders, transport workers and other economic and social groups although these are not covered in the literature on urban commons.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Raman (2010 :105).Street traders, Place and Politics. A case study of Bangalore. PhD Dissertation, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- ↑ This estimate is based on the tokens issued to traders by the land managers every day.

- ↑ Raman (2010), Street traders Place and Politics: A case study of Bangalore. PhD Dissertation, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- ↑ Raman (2010:233). Street traders Place and Politics: A case study of Bangalore. PhD Dissertation, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- ↑ Interview with street traders and retailers in Parrys corner in Chennai, dated September 2010.

- ↑ See also Mukhija 2005.