P2P Mode of Production

* Book: The P2P Mode of Production: An Indiano Manifesto. Translated by Steve Herrick.

E-version supplied by Matthew McNatt and reformatted by Simon Grant

The P2P Mode of Production: An Indiano Manifesto

By The Indianos

Translated into English by Level Translation

(This is the whole book.)

Index

- General information about this book

- Introduction

- The emergence of distributed communication networks

- The drama of the scales and the global crisis

- The new free software model and the hacker ethic

- The New Industrial Revolution

- The P2P learning system and production

- The political reflection: commons, asymmetrical confederalism, and the principle of subsidiarity

- Conclusions

General information about this book

Acknowledgments

This book was originally written in Esperanto and then translated to Spanish by Natalia Fernández, María Rodríguez, and David de Ugarte, members of the Grupo Cooperativo de las Indias, who devolve it to the public domain. Without the debate and discussion among the Indianos, our readers, and important theoreticians from around the world like Juan Urrutia, Michel Bauwens, or Kevin Carson, this book would not have been possible. We dedicate this work to them.

What you can do with this book

You can, without prior permission from the authors and editors, copy it in any format or medium, reproduce its contents partially or fully, sell copies, use the contents to create a derived work, and, in general, do everything you could do with an author’s work that has passed into the public domain.

What you can’t do with this book

Placing a work in the public domain means the end of the economic rights of the author over it, but not of moral rights, which are inalienable. You cannot attribute total or partial authorship to yourself. If you quote the book or use parts of it to create a new work, you must expressly cite both the authors and the title and edition. You cannot use this book or parts of it to insult, injure, or commit crimes against people’s honor, and, generally cannot use it in a manner that violates the moral rights of the authors.

Introduction

The current crisis, the deepest and longest in the history of capitalism, has sparked a debate around the world about what appears, more clearly with each passing day, to be the simultaneous destruction of the two principal institutions of social and economic life: the State and the market. Never in living memory has the economic system been so universally questioned.

On the other hand, never before have technical capacities been so powerful, and, more importantly, so accessible to people and small organizations. In fact, never before have so many small businesses taken part in the world market. Nearly free [gratis] peer-to-peer communication technologies allow them to create the largest commercial networks in history. The emergence of free software (which, by itself, represents the largest-ever transfer of value to the economic periphery) empowered them with unexpected independence. Millions of small businesses around the world, especially in Asia, were able to coordinate among themselves this way and hone their products just as new markets were opening up to them. It’s the “globalization of the small.” It’s not a marginal phenomenon: never before have so many people around the world escaped poverty.

If we look closely at these tendencies, we’ll find interesting contradictions: the crisis has its origin in large-scale industries, and in fact, it’s the largest of all, the financial industry, that set off the process and kept it going. However, the new emerging technologies are about scope, not scale: the free software industry isn’t sustained by big, monopolistic global businesses with global networks of commercial subsidiaries, but rather on a new “commons of free knowledge” that can be downloaded, modified, and even sold by anyone. The relationships in the construction of this new commons have no central leadership or hierarchy, but rather are based on the free concurrence of projects and on relations between equals. The businesses in this industry don’t win fame and income by creating scarcity. They develop their reputation on innovative contributions to the commons, and their benefits are born of the sale of work hours alone.

Free software was the first industry based on a completely different system of property and production: the peer-to-peer, or P2P, mode of production. Later on, in the middle of the crisis, new tools would appear, from three-dimensional printers to industrial design methodologies, and new sectors would explore new branches of the commons.

The objective of this book is to show how the economic crisis is, in reality, the crisis of large scales, but above all, to show how we still have the opportunity to take a step towards a new mode of producing that’s based on a new, cooperative way of competing, a new work ethic, and, above all, on the building of a new commons, a knowledge commons open to all.

The emergence of distributed communication networks

“Under every communication architecture, there hides a power structure.” That’s why communication technology is closely linked to social movements and governmental structures and, on the other hand, why it limits the growth of social relationships in every age.[1]

The world of centralized communication, the world of snail mail, defines absolute monarchy and even the Jacobin republic born of the French Revolution: a centralized State, newspapers produced in the capital city, submission to the center and its identity in all social relationships. In fact, it wasn’t the French Revolution, but rather the spread of the telegraph created by Morse, that would allow for the decentralized structures that characterize representative democracy and international relations, from the media system based on the relationship between international agencies and national newspapers to the pyramid-shaped organization based on local groups with a structure of regional, national, and international coordination on top. We’re not exaggerating when we say that universal suffrage, pluralism, and also multinational businesses and imperialism, would not have been possible without the universalization of decentralized communication.

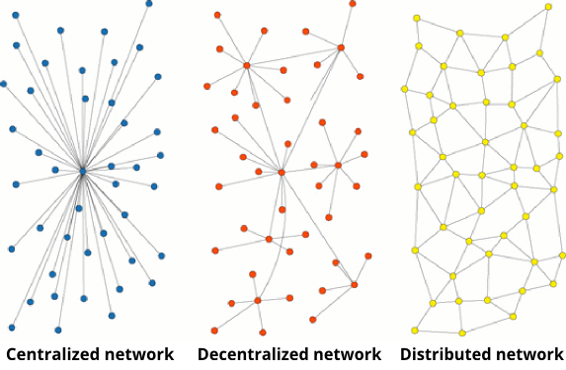

But decentralized is not distributed. Decentralized structures define hierarchies: the higher we are in the informational pyramid, the more independent we’ll be to access the information, and the more easily we’ll be able to disseminate it later. Communication between the basic nodes—which are what most people in States, parties, or businesses belong to—depends on their representatives and regional coordinators, who have the power to filter and decide what to disseminate down and what to send up. The decentralized world is, in each local subnet, centralized. Only when distributed communication appears will a new approach to social relationships be possible.

If we extract the central node from a centralized network, the network itself disappears. If we extract one of the local centralizing nodes from a decentralized network, the network will break into various subnets out of contact with each other. What defines a distributed network is the ability to extract any node without cutting off any other, which means no node can filter information on its own. If any group of centralizing nodes produces scarcity—through democratic or authoritarian means—distributed networks turn decentralized pluralism into distributed diversity. Communication between peers has its own logic.

The first demonstration of the social consequences of the Internet would be the birth and rise of the blogosphere, the first distributed medium of communication. It’s no secret that the spontaneous movements in Manila (2000), Madrid (2004), France (2005), Athens (2007) or the “Arab spring” originated in the blogosphere’s ability to promote a new social consensus. Moreover, the activists of the large democratic movements like “the Color Revolutions” in the former Communist states were able to take advantage of distributed communication to build new social majorities, even without freedom of the press or assembly.

But, while the political consequences of distributed communication were the most visible, they weren’t the only ones.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the USSR, large-scale Western businesses pressured governments to open foreign markets. They soon found opportunities by dividing up their production internationally among many smaller, autonomous businesses. The phenomenon was called “globalization,” and it created global worries. But an unplanned evolution took place among entrepreneurs at the periphery, which would change the goal of the “new world order.” In 1999, the same year the media told the world about the massive demonstrations of the “antiglobalization movement” in Seattle, the first big online Chinese bazaar appeared: Alibaba.com. It was just the first manifestation of a large, underground movement. Soon, in all sectors, global networks of merchants and industrialists became aware of the possibility of coordinating and competing with the big businesses that were accumulating the better part of the value of the international division of labor. Thus began “globalization of the small.”

At the same time, during the second half of the Nineties, the “hacker movement” exploded with the growth of the use of the Internet. It changed profoundly, and soon, its first major contribution—Linux—was born, and with it, the world of free software became the basis of the first P2P industry.

The drama of the scales and the global crisis

Economic theory tells us that a business reaches its optimal dimension when the costs of production over the long term are minimized. After this point, if we increase all the factors by the same percentage, the average costs of production will grow. Then we have “diseconomies of scale.”

The optimal scale of production is based on the productivity of the factors, which, in turn, depends on what the best available technology is in that sector and at that time. New technologies will need a smaller quantity of factors to produce the same quantity of final product, and, more importantly, will be first to reach the minimum cost of production, and therefore, will cause “negative returns on scale.” This way, more productive technologies reduce the average size of organizations.

However, the constant growth of productivity since the end of World War II, while reducing the average business size, doesn’t seem to have influenced the size of big businesses. On the contrary, they’ve grown constantly up through today. In the 90's, when the largest wave of mergers and acquisitions in history took place, the new giants generally invoked “positive returns on scale,” which is difficult to believe because, at the same time, the same businesses were dividing up their production processes and pressuring regulators to sign free-trade agreements which would let them “break value chains” up among subcontractors around the world. If the concentration of businesses was necessary to reach new and greater optimal scales, why hollow out the structures themselves to become a de facto coordinator of lots of autonomous, small-scale businesses around the world?

Two forces give rise to this contradiction: “economic rents”—non-market benefits—produced by the possibility of putting conditions on states and markets, and the needs of Big Finance.

The three main “neoliberal” policies that have been pushed since the 80's—financialization and securitization, opening of peripheral markets, and the hardening of legislation on “intellectual property”—are tools at the service of large-scale capital, at the scale that the financial system needed to “make room” for the growing pools of inactive capital. Ironically, capital was not made active for small-scale business, because the financial sector itself was the main oversized industry… and also the main beneficiary of economic rents created by political power gained through size.

Symbolically, in 1996, pressure from the financial industry resulted in the repeal of the Glass-Stegall Act, which had been approved in the US after the Crash of ’29 to avoid the infection of the financial system by future speculative crashes. This law prohibited investment banks from buying commercial banks. But excessively large scales call for even larger scales. The new monsters were soon “too big to fail,” giving capitalists the most valuable economic rent of all: guaranteed future survival, for free, courtesy of the State itself.

But the greatest irony of all arrived at the end of the decade, when one of the clearest results of the reduction of optimal scales, the nascent Internet sector, became a financial bubble. It was inevitable. The number of profitable projects and the first P2P sector’s need for capital weren’t enough for the financiers trying to get in on the action. Business plans were inflated, capital flowed… and the first great sectoral crisis of the twenty-first century arrived.

It didn’t take many years before the Internet sector once again began to look attractive to big investors. New businesses became gigantic: Google, Facebook, Twitter… they seemed designed to justify owning large infrastructure (which was built on technologies whose main contribution was precisely making big investments unnecessary, thanks to communication between peers). Sadly, to do that, they had to recentralize the network, or at least try to. But big infrastructure needs big capital, and besides, large communication groups—themselves large-scale businesses—know well how to capture rents on centralized structures. The new global businesses, though technological and historical aberrations, would be greeted hopefully both by the big newspapers and by financial markets.

But, was there no one who really needed huge amounts of capital? Actually, yes. In Africa, the Americas, Asia and in general, large parts of the underdeveloped world, they were about to build large infrastructure, and they needed massive investments. But, as economist Juan Urrutia wrote in 2005, they never received capital, because the housing bubble, together with complex financial tools, made it unattractive to invest large quantities outside of the large-scale financial markets.

The big bubble machine finally, although only partially, broke down in 2007. Huge waves of speculative capital rushed in, some destroying raw material markets, others clinging to States, turning the speculation crisis into a sovereignty crisis… The inadequacy of financial capital to the new and smaller optimal scale is not only the origin of the crisis, it’s present in each and every one of the aspects of its development.

When technology drastically reduced the optimum scale of production, capital, instead of adapting, fled towards the opacity of financialization and short term movements. As long as risk preferences are not modified to permit capital to be reintegrated into real production (which is smaller and smaller-scale), the root cause of the crisis will continue operating. Unfortunately, these giant financiers have a short-term exit strategy: support themselves via the capture of the State through mega-corporations and debt… driving decomposition and the destruction of productive capacity.

The new free software model and the hacker ethic

The hacker ethic is not a truly new thing in history. We can recognize it in the moments of originality in science, in the first engineers of the Industrial Revolution, in the great personalities in physics, economy, medicine… but the new hackers appeared not long before the precise moment in which information, technology, and creativity would become the majority of value produced. At this moment, large scale would begin to reveal “negative returns on scale” in the management of intellectual capital.

Born in electronic media around universities and connected with activism through electronic privacy issues, the hacker movement evolved rapidly towards an alternative organizational system for self-organized researchers in different fields.

Hacking is using knowledge we have about a system of any type to develop functionalities for which it was not originally designed, or to make it work towards new objectives. In the press, they’re called “IT geniuses,” or even “pirates,” but the new hackers are, in fact, much more. The sociologist Pekka Himanen showed in a famous book [2] how hackers, to create value, need free access to knowledge and their peers.

For hackers, knowledge itself is a motivation for production, and in general, for life and work in community. They don’t learn to produce more or better, they produce to know more. Because learning is their goal, their life can't be divided up between work time and “free” time. Time is always free, and as such, productive, since a hacker practices multispecialization as a way of life. Freedom is the principal value, as the materialization of personal and community autonomy. Hackers make no demands on others—governments or institutions—to do what they think should be done; they do it for themselves directly. If they make any demand, it’s for the removal of barriers of any kind (monopolies, intellectual property, etc.) that prevent them or their communities from doing it.

In this framework of values, free software’s first great victory was born: the construction of a complete free operating system—Linux. Never again would the hacker movement be part of the underground. A new electronic commons appeared before millions of people’s eyes. It would quickly but profoundly and permanently change the star industry of the previous decade. It would go from a few large-scale businesses to a far-reaching system with many small groups, projects, and businesses, that rested on a unique, but multiform, diverse, and dynamic commons.

Not long after that, the cycle and the structure of the production of free software, would appear in other fields. Not coincidentally, the production of immaterial cultural objects—music, literature, and audiovisual creation—had taken advantage of P2P technology before others. But, by the same token, it had also suffered an attack from new intellectual property laws pushed by the large-scale culture industry.

And not many years ago, when the large-scale systemic crisis was at its weightiest, the same P2P production cycle and structure took their first steps into the manufacture of physical objects. Today, we can build more efficient, cheaper, and more attractive cars, free from intellectual property, in any small workshop, thanks to projects like Wikispeed.

In the last three years, there’s been a large increase in the number of industrial manufacturing projects based on the possibilities of high productivity on a small scale, based on a commons of technical knowledge. The “Open Source Ecology” project alone is working on the design of forty basic industrial machines, from a wind generator to a tractor to a brick-making machine.

But what is the P2P mode of production? What is the P2P production cycle?

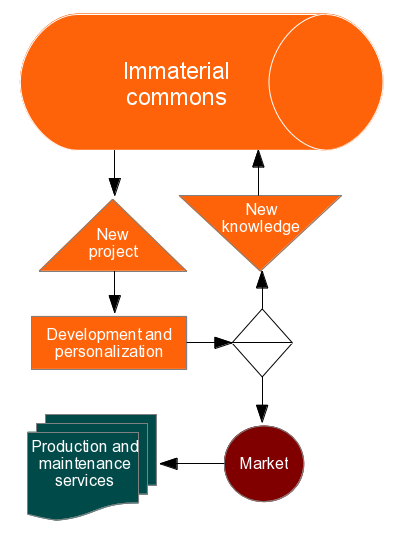

The center of the cycle is the knowledge commons: intangible, free of cost, and free to anyone to use. It’s the characteristic form of capital in production between peers. From this starting point, new projects are born. Because there’s no central authority, they can be evolutions of earlier projects in the commons—even customizations for concrete needs—or they can try to meet different, truly new, objectives. This way, new knowledge is produced as projects materialize and develop.

New knowledge is incorporated directly to the commons, the center of P2P accumulation, but also goes out to the market, where it can be incorporated into customization, production, and maintenance services sold by small-scale businesses.

It’s important to point out that, in the P2P mode of production, market and capital are defined fundamentally differently from the current system. The key to understanding it is the concept of “economic rent.” Rent, in this context, is any extraordinary benefit, generated outside of the market, because of the place occupied by the business. “Natural” monopolies (normally created by over-scaling), legal monopolies (like intellectual property), and State favors are the most common sources of businesses’ rents. It’s also, as we saw before, the main motive for over-scaling organizations, and the most common argument for Big Capital’s “need” for new industries.

All these rents disappear in the P2P production system. Only one rent remains: the one produced temporarily by innovation. Whoever creates new technologies or products has a short time to take advantage of their uniqueness in the market before the new knowledge enters the commons, allowing others to offer it, and “dissipating” the innovation rent for its creators… which starts the cycle all over again.

Because the market will only bear the value of the labor contained in services, businesses need to innovate constantly to win short, temporary rents from successive innovations. That’s why the P2P mode of production is truly a machine for making abundance, which accumulates in the form of an ever-growing and universally usable knowledge commons. All without needing central control, hierarchy, or large-scale organizations.

The New Industrial Revolution

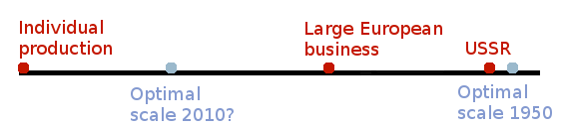

If we laid out the different possible scales on a spectrum, the starting point would be the still-utopian goal of individual production. That would be a world in which any person could, by him/herself, produce anything. At the opposite end, we’ll find the defunct USSR: where a single business—the State—plans and produces everything for the market. The current optimal scale is somewhere in between, depending on productivity and technology.

So, the growing incompetence of the Soviet economy from the '50s to the '90s would be, at least in part, a consequence of the growing distance between the scale of the State and the optimal scale, which, every year, was a little farther to the left on our spectrum.

Today’s crisis, which was first Western and then global, clearly shows how financial capital has not adapted to the smaller optimal scales of production created by technological evolution. The Western economy is at a point to the left of the average scale of the big businesses of Europe and North America.

It’s not the first time. In the '70s, Europe suffered from a similar lack of adaptation, and the big European industries were redesigned. But now, a critical point has been reached. This is a moment in which quantitative changes in productivity result in qualitative changes in industrial organization, which, in turn, require a transformation in financial, commercial, and institutional structures.

At this point, a large part of the old possibilities won’t work, and the new ones will take the economy and the power structure to a very different place.

The traditional economy of large scales can’t overcome, or even resist, the current crisis. Large scale prohibits innovating, managing knowledge created in its interior, or contributing to social value. Its own nature prevents it. The paralysis of the big, monster businesses keeps them from innovating, just when it’s needed most. And we’re already well past the moment when the standardization of services made them incapable of satisfying their clients. Western Big Businesses are not that far from the erosion of quality that we saw in Soviet businesses during the '70s.

But, never before has knowledge been so important—in fact, more important than monetary capital—and never has personal production been so close. 3D printers have made incredible progress without receiving a millionth of the State aid that Big Business, “business incubators,” and associations of large-scale organizations have received to grow, expand overseas, or simply survive.

The expansion of the commons to the world of low-cost industrial machinery and the design of houses or cars for local production pushes the limits of what’s possible, but also shows an alternative system already functioning without rentiers, and without the old, harmful logic of scales. As The Economist—hardly a suspicious, radical rag—assures us, parallel to the crisis, we are living through a true “New Industrial Revolution.” These technologies, even if they are a bit immature, can be a solid base to confront the consequences of the financial crisis in the local productive community, in the industrial microenterprise, in the SME, in the neighborhood workshop, and in the component factory.

And according to everything that we’ve looked at in the preceding pages, the formula for the New Industrial Revolution seems clear: Knowledge commons + distributed networks + high productivity on a small scale = virtual macrospaces of abundance + micromarkets of production and services = local reindustrialization.

The P2P learning system and production

Meanwhile, in parallel with the growth of the commons, another important evolution in the P2P mode of production is the appearance of a true “P2P learning system” and a “P2P theoretical research system.”

Around 2008, when the most-recognized US universities began to freely publish their courses as videos on the Internet, other US institutions and the European university model were called into question. If learning with the most modern media in the most famous institutions had become free, what were their students buying? Just a certification that they could soon buy at MIT or other big universities?

Hackers, who are traditionally self-taught, had another take on it: a new, free confluence of learning tools was emerging, and now, one could aspire to a P2P learning system. The projects soon multiplied.

From the hacker ethic perspective, the university, especially in continental Europe, is part of a teaching system. For every teaching system, the most important result is the certification of the students for the State and the labeling of their knowledge for large-scale businesses. The teaching system is part of the rents system. Hackers don’t want to be taught, they want to learn. Labeling and certification is useless for them. Because the hacker ethic is an ethic of action, the only useful indication of knowledge in the P2P mode of production is contributions made to the commons.

However, the university has another function traditionally linked to hackers themselves: that’s where basic scientific theory and knowledge are produced. But the research atmosphere at the university is no longer hacker-friendly. In fact, it’s almost feudal, and more and more closed and dependent on the direction provided by the institutions and big businesses that control rents. As a result, the P2P mode of production needs its own structure for this.

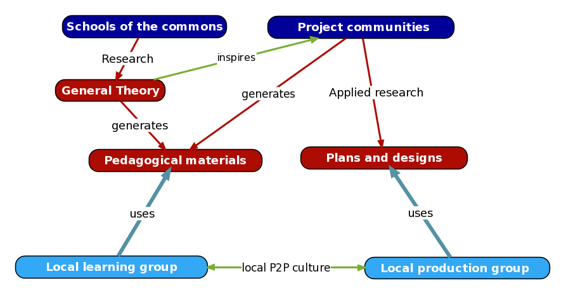

Institutions like the P2P Foundation,[3] which appeared around the first decade of the century, grew and gained weight in the new context, becoming true “schools for the study of the commons.” The discussion on the need for an institution to serve as a meeting point in the debate between the different schools and projects finally clarifies the map of the whole P2P learning and research system.

The P2P mode of production closes the gap between action and knowledge. The development communities of various projects (OSE, WikiSpeed, Mozilla, etc.) create products, but also the research and innovation linked to them. Applied knowledge development has a place there. But the place of theoretical research is in “Schools of the Commons,” which encourage free research on social theory and basic science. They don’t offer teaching or degrees, but they produce pedagogical materials through specialized work groups. Local learning groups use these materials along with materials created by development communities to become activators of local P2P culture. Right now, as we write this chapter, dozens of local learning groups are being created with different names and legal structures: associations, cooperatives, local workshops…

The political reflection: commons, asymmetrical confederalism, and the principle of subsidiarity

The progressive reduction of the optimal scale of production is the origin of the crisis, but also of the possibility of the P2P mode of production becoming a reality. But if scale is reduced in production, wouldn’t it be logical to think that public administration also needs to be reduced? Big, decentralized States have many of the problems of big businesses and are also the main objective of rent captors. As libertarian and anarchist thought has asserted from Proudhon to Hayek, small-scale administrations with confederal ties between them would be a defense against the capture of rents from public power.

On the other hand, tensions would inevitably arise between the universal nature of the commons and the local nature of a growing part of production and physical distribution. The autarkic and even isolationist temptation quickly appears, leaving aside one of the most hopeful elements in the emergence of distributed networks: the erosion of old identities based on nation-state and the appearance of new transnational and non-national identities. But, the evolution of the transition toward the P2P mode of production really has gone hand in hand with the emergence of new transnational communities. Many of them, from China to Senegal, have experienced a variety of forms of economic autonomy.[4] Their role in the future will be no small thing. The P2P society will know commerce and mobility over long distances. If it didn’t, it would endanger its capacity to create well-being and social cohesion.

Certainly, smaller scales mean more local production, but low-cost intercontinental merchant transportation—possibly based on renewable energy—will continue. Revaluing local production, freed from subjection to gigantic scales, absolutely does not mean a new, localist autarkism. It’s not logical to think of this transnational phenomenon as being limited to the deliberative processes that create the knowledge commons.

If the birth of transnational identities continues and converges with the general development of the P2P mode of production, the transnational level will empower the local level through identitarian communities that may well lead to a “continuum of of freedom and well-being” over and above the legacies of the different levels of development and nation-states in decomposition. Phyles will surely be vectors of communication, commerce, and the transnationalization of citizenship. The P2P mode of production doesn’t reject globalization, but rather redefines it from the communal and local level.

Different proposals have different interpretations of this goal, but possibly the clearest is Juan Urrutia’s work on redefining confederalism, using the concept of “asymmetrical confederalism.”[5] This is confederalism in the classic cantonalist sense: local, autonomous, democratic governments that voluntarily share parts of their budget with other administrations at the same level through supraterritorial organizations. So, asymmetry doesn’t just deal with territorial governments, but also with cross-border organizations.

On the other hand, the definition of the electoral body—who has the right to vote—is appearing in more and more places at the center of the political debate. For example, local elections in many cities in Europe are decided by the “emigrant vote,” which, many times, is the vote of the grandchildren of those who emigrated—and barely retain any “cultural” relationship with the origin of their grandparents.

It’s an interesting phenomenon. On the one hand, states in decomposition tend to prioritize the principle of nationality over citizenship, freeing themselves from the contractual idea that sustains the latter in favor of the identity affirmation that defines the former. But, on the other hand, the very definition of the imaginary national community based on origins, throws into question the very possibility of the national character of the State, due to the growing transnationalization of linguistic and cultural groups: as nationalistic as the administrative apparatchiks would like to be, not everyone who fits the description is there, and not everyone who’s there fits the description. We should recall the Israeli debate between the defenders of an ethnic state like the current one—which gives citizenship to any ethnic Jew in the world—and the defenders of a reform towards a national state.

The authoritarian nationalist route leads to inward homogenization and xenophobia and the outward expansionism of the census. That is, they don’t want to let a portion of the neighbors vote, and yet the right to vote is given to people who never lived in the place. The inevitable result is that lots of people in Galicia, Asturias, and Israel don’t understand why the mayor of their town ends up being decided by a group of people they’ve only seen a couple of times on vacations, likely paid for with money that was theoretically dedicated to development.

The idea of asymmetrical confederalism is presented here as something sensible and applicable in the short term with no major drama. The idea is that if there exists a cultural commons to be maintained, it should develop its own transnational structures. These would be somewhat different from the W3C or the Mozilla Foundation: its members organizations would have a certain globally recognized cultural autonomy to define their own cultural and linguistic policies among their members. They could also develop policies of cohesion and economic solidarity. But the administration of what’s local will be decided by a census based exclusively on vicinity, and looking only at the principle of citizenship.

Currently, some States, like the Austrian and Spanish States, include options on their tax forms that allow taxpayers to decide whether or not to designate a percentage of what they pay to the religious organization they belong to, or to “other social interests” defined by the State itself. We can imagine a similar way of including the transnational and communal dimension in a confederal system with fiscal sovereignty, like the Swiss system: neighbors vote in each place, but when they go to pay their taxes, they can choose to send a part to a transnational organization that represents them in the identity to which they subscribe, whether that be cultural, based on a commons identified with an “origin” (Gibraltarian, Brazilian, Basque, or Jewish, for example) or a synthetic transnational community (Indiano, Muridi, Focolara, Esperanto, etc.), or other productive communities of the commons (Linux, care of the oceans, etc.), all organized as different international foundations or organizations.

It should be highlighted that all this is only really applicable if there exists regional fiscal sovereignty, which, clearly and not coincidentally, is the base of direct democracy. And one more clarification is still necessary: the coherence of the whole system leads to a redefinition of the principle of subsidiarity to also include the relationship between public and communal property. In fact, all asymmetrical confederalism necessarily defends the supremacy of administration in common: governments shouldn’t administrate anything that could be managed as commons.

Conclusions

Since World War II, productivity has multiplied, which has drastically reduced the optimal scale of production, sidelining the State capitalism of the Eastern countries first, but also jeopardizing Big Business in the U.S. and Europe.

During that time, the structure of communications was also transformed: we’re in the transition from a decentralized world, the world of the telegraph and of nations, to the distributed communication model, the world of P2P communication.

The union of these changes, along with the removal of commercial barriers in the '90s, resulted in a constant growth in commerce based mainly on the emergence of new, smaller-scale, less capital-intensive agents on the periphery. The direct consequence was the greatest reduction of poverty in human history, but also a remarkable increase in inequality and economic instability.

The main cause of this countertendency was financial capital, which didn’t adapt to the reduction in scales, but, on the contrary, increased them still more, supporting itself on “financialization” and “securitization,” distancing itself from the productive system, and regularly instigating speculative bubbles. Its strategy for scale included the hardening of legislation on intellectual property, needlessly redefining the Internet through recentralizing structures (Google, Facebook, etc.), and fundamentally redoubling pressure to capture States.

This strategy can only lead to the simultaneous destruction of the market and the State, a phenomenon that we call “decomposition,” and which occurs parallel to the destruction of productive capacity and the crisis and war which precede and accompany it.

But at the same time, with the birth and development of free software, there appeared a new way of producing and distributing, which was not centered on the accumulation of capital, but rather the accumulation of a new commons, which is to say, of abundance, in which the market eliminates rents—from intellectual property, position, etc.—to instead base itself on paying for labor and rewarding innovation and adaption which, in turn, enrich the commons.

This is what we call the P2P mode of production, and it works to produce software, physical objects, and all kinds of services. It accumulates abundance in the form of the knowledge commons and dissipates rents without requiring central control, hierarchy, or large-scale organizations.

These technologies, even if they are still a bit immature, can be a solid base to face the consequences of the financial crisis in the local productive community, both in industrial microenterprises and in SMEs, from the neighborhood workshop to the component factory.

Meanwhile, in parallel with the growth of the commons, another important evolutionary step in the P2P mode of production is the appearance of a true “P2P learning system” and a “theoretical research system” of its own. While applied knowledge already has a place in the development communities of assorted projects (OSE, WikiSpeed, Mozilla, etc.), the social theory of the P2P mode of production finds its place in foundations and Schools of the Commons. And dozens of local learning groups are being created with different names and legal structures.

Finally, the first political proposals are appearing that reflect the structure of administration. These proposals are centered on the concept of “asymmetrical confederalism,” which, in turn, necessarily postulates the supremacy of the commons. For the new confederalists, governments shouldn’t manage anything that can be administered as commons.

To conclude, all these diverse phenomena emerging before our eyes, from the financial crisis to locally produced cars, 3D printers, the hacker movement, and free software, are a real part of a larger crisis, the crisis of capitalism as we’ve known it: large-scale, decentralized, hierarchical, and rent-seeking.

In contrast, we are researching the fundamental characteristics of the new mode of production, based on small productive scales, relationships between equals, a new hacker work ethic, and, above all, the knowledge commons. It seems like a good basis for the necessary transition towards a new social and economic system. And, most importantly, it’s already here, it works, and it’s not a morality tale, a silver bullet, or well-intended activism.

The P2P mode of production isn’t some ideologue’s plans for the future. It’s not a partisan thing or the dream of some small group of true-believers. It’s a real (if young) alternative for the organization and reconstruction of the productive community on a new basis. It doesn’t need leaders or governments to develop, but rather the work of all those who want to gain resilience for their communities based on competition without rents, and on collaborative labor.

Notes

- ↑ See El poder de las redes, David de Ugarte, 2005, several editions in Spanish, Galician, Portuguese, and English. Downloadable here and here.

- ↑ The Hacker Ethic and the Spririt of the Information Age, Pekka Himanen, 2001, several editions in English, Finnish, Spanish, etc.

- ↑ Known by different names in different languages.

- ↑ See Files: de las naciones a las redes, David de Ugarte, 2008, several editions in Spanish and Galician. Downloadable here.

- ↑ See Nuevos territorios, Juan Urrutia, 2012, Basques 2.0 Fundazioa. Archived version No longer downloadable here.

Commentary

Steve Herrick:

"This document is a call to action, based on Las Indias’ analysis that the reduction of the optimal scale of production is the root of the current crisis — in Spain particularly, but also worldwide. This is a grave threat for huge corporations (and to a lesser extent, national governments), but very promising for small enterprises. That’s because the core of the P2P mode of production is a “knowledge commons” available to all.

Abundant information on every topic imaginable, but especially on small-scale production, means that local producers can freely choose the most effective, efficient and accessible processes, without the shackles of intellectual property. This will lead to a blossoming of local enterprise. And that’s where you can take action."

(was at: english.lasindias.com/announcing-the-translation-into-english-of-the-p2p-mode-of-production-an-indiano-manifesto/)

More Information

- In Spanish: