FairCoin

Description

Background

The world of cryptocurrencies started with the enigmatic person or collective Satoshi Nakamoto. His origin or place of residence remains unknown. Everyone talks about him, but nobody really knows him.

In 2008 he published his white paper, introducing a disruptive technology thao

Satoshi not only launched the theory, but also designed it and put it into our hands. The following year he launched a free software application to create the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin. Then the race began. Hundreds of coins have been developed from this initial one, each with its own peculiarities, but generally respecting basic features such as blockchains, encryption, pre-coined money supply, etc.

We are at a historic moment. Peer society alternatives have been growing fast, and cryptocurrencies provide us with just the tool that was missing to enable us to change the rules of the game. A revolution of economic, technological and social systems is taking off.

FairCoin

FairCoin is a currency created for the purpose of promoting equality and economic justice. 50,000,000 faircoins were created in March 2014, and between March 6 – 8, were distributed through a massive give-away called an “airdrop” at a rate of 1000FAC/hour to anyone who made a request.

FairCoin became the first currency which needed no initial mining but was distributed equitably in order to promote equality of financial possibilities. Still, obviously an airdrop on an Internet forum has a very limited scope, and therefore the initial distribution isn’t quite sufficient in its equity purpose.

Currently, FairCoin has been adopted by fair.coop's promoters as the cooperative’s currency for use as a means towards global economic justice.

The key purposes of the cooperative regarding FairCoin is using it to generate economic redistribution while it also increases the level of justice, supports the empowerment of grassroots groups, transformation of social and economic relations, and creation of commons (Fairfunds).

See also: What is a CryptoCurrency?

History

FairCoin Development Team:

- "6 of march one anonymous guy created the coin

- About april 23th, the anonymous developer leave the coin

- About may 6th the community take over the coin, and I was one of the people involved that done this takeover.

All of this is documented in the whole bitcointalk thread:

see specially this note: https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=702675.0

Note from the FairCoin Development Team:

Faircoin begun in march with this First ANN

https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=487212.0

FairCoin was abandoned at the end of April 2014 by its original developer; but not after promising huge projects, private investors, and much more. The FairCoin community was left to sit with unfulfilled promises, high hopes diminished, and a moral completely drained. A few leaders in the remaining community organized a new development team, consisting of some of the most devoted members.

This was the context of our second ANN

https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=601280.0

From the initial community take over, a team of three committed individuals, was who really give continuity to the dev team: smartaction, drakandar and thokon00

Because the creator of the second ANN was not really involved and this was inefficient to have a good communication, we decided to close the second ANN at the same time of the First hard fork, and we created this third ANN really accessible by the current FairCoin Development Team."

Interview

Enric Duran and Stacco Troncoso, interviewed by Cat Johnson on the cryptocurrency of Fair Coop:

Shareable: What's the importance of having a cryptocurrency focused on alleviating economic injustice and promoting social good?

Duran and Troncoso: Up until now, cryptocurrencies have held great potential, but it hasn't always coincided with a practicality that would alleviate [social] ills. Certain elements such as bypassing the need for central banks are steps along the way, but there was something missing. A holistic social and economic system is urgently needed to address the inequalities inherent in the current system.

How is Faircoin different from other cryptocurrencies?

For one thing, Faircoin is technically different in the currency generation protocol used. Faircoin uses Proof of Stake (POS), instead of Proof of Work (POW). The use of POS prevents any unfair advantage which could be afforded to those who can access and invest in the environmentally destructive means of mining (destructive for its consumption of energy and resources needed for the servers). What really makes Faircoin different is its specific use as a tool for Fair.Coop, as a cryptocurrency designed to act as a store of value for Fair.Coop and its redistribution of capital to socially and environmentally coherent projects.

What's the relationship between Fair.Coop and Faircoin? How will they intersect and/or interact?

Our intention is to be “Fair in name, fair in practice.” Fair.Coop uses Faircoin as its social capital and store of value. Fair.Coop is Faircoin's conscience—it's a cryptocurrency attached to commons-oriented responsibility.

Fair.Coop already holds 20 percent of all Faircoins in existence, which guarantees that the growth of the currency's value will go to the common good. This is guaranteed by Fair.Coop's democratic accountability system.

Do you see Fair.Coop and Faircoin working on a global scale? What could that look like?

In fact, Fair.Coop can't be anything but global; it's been specifically designed to be global; for this reason, we call it the Earth Cooperative. It's not a scaled-up local project. One of Fair.Coop's key objectives is to facilitate a global body of knowledge, capable of generating concrete impact locally.

At any rate, we could make a working distinction between two sets of mechanisms that'd be produced by Fair.Coop: global and local. At the local level we'd be seeing local, specialized mechanisms and knowledge which, in turn, would feed into a global open knowledge economy comprised of, among other things, valuable data and monetary and economic tools. This will be a bidirectional relationship, as both parts will nourish one another for the benefit of the whole."

Who will the funds raised with Faircoin go to? Do you already have organizations or projects in mind? If so, where are the organizations located?

Who the funds will go to isn't something that's decided by the promoting team. Identifying who the potential benefactors are and following through is an ongoing democratic process of the whole coop, as it's coming together right now where each of the different Funds is co-managed by a council that works in conjunction with the other Funds, as well as with the entire community built around Fair.Coop.

The type of organizations we want to work with will be those who could potentially generate peer production in the material plane, as well as benefit from the shared knowledge accrued by the coop. We also want to focus on projects that lack the necessary means to activate this type of peer production.

Other examples would include strategic projects that can add more value to the global commons. Projects which, on their own, maybe wouldn't have the ability to network at this scale to share their knowledge. The projects would also benefit from the moral and material support of a global community if and when attacked by hostile interests. All in all, Fair.Coop will increase the resilience of these projects.

More than naming specific organizations, we are very open to being approached so that everyone can participate in Fair.Coop's co-creation and ongoing development. We are also very interested in empowering the Global South to increase its resiliency. When we say Global South, while there's an undeniable geographical truth to this, we also mean the 99%, independent of where we may reside." (http://www.shareable.net/blog/faircoop-using-cryptocurrency-to-bring-economic-justice-to-the-world)

Technical Details

Introduction

FairCoin is the monetary base system for FairCoop. We constantly drive development of the FairCoop/FairCoin ecosystem further and shape the individual components to fit our vision: building tools to enable everyone to participate in a fair economy on a global scale.

We decided to create a new version of FairCoin which corrects issues we encountered. The current version of FairCoin relies on PoS (proof-of-stake) which cannot be considered fair, because it confer an advantage on the already rich. Therefore we needed to come up with a new way to secure the network. We call it PoC (proof-of-cooperation). This innovation will finally make FairCoin fair, secure, and sustainable.

The draft we present here is meant to start a discussion on what the new version would look like. Many hours of voluntary work have already been put into building the basic concept and the white paper. The focus of the draft paper is mainly on the technical and implementation side of the FairCoin2 project. Many more aspects besides the technical have to be taken into account and elaborated on.

So, here it is the first draft of the FairCoin V2.0 white paper. Enter the fair dimension of cryptocurrency and download the PDF file now.

Technical features of FairCoin

- 99.99% POS: It is a hybrid POW / POS system but money creation is 99.99% POS. Thus, the majority of faircoins are minted, ie, the system works thanks to everyone’s savings.

- As for security, there is a POW block every 5 minutes, and a POS block every 10 minutes. These two methods are combined to provide the best of each in securing the system.

- The low remuneration for mining, 0.001FAC / block, prevents energy waste since using high consumption mining devices is just not worth it.

- Money Supply of 50,000,000 coins mined out in the first block and initially spread out to all who applied for it, so that not only those with capital or mining resources could have access.

- Savers, ie, people connected to the network and minting, will receive 6% of the coins during the first year, 3% the second and 1% from the 3rd year on.

Some of these features may be changed by consensus on the network in benefit of FairCoin, a topic on which Fair.Coop and its members have a lot to say.

In fact, since Fair.Coop is based on open political participation, we can say that Fair.Coop adds to FairCoin with an approval based on agreements between humans– which, to our knowledge, no other cryptocurrency does. We call it “human-based consensus”.

Buy Faircoins

You can currently buy FairCoin in the main website [1]. You can also buy FairCoin in other places on the Internet like exchanges for example.

You can download the FairCoin wallet here. Once downloaded, we recommend you check the FairCoin Academy where you can find courses and tutorials to start using FairCoin.

Mint Faircoins

You can participate as a FairCoin active node anytime by using the software on your computer, waiting for 21 days, and then start minting. Meanwhile, you can participate by mining (POW).

After 21 days, if your coins haven’t been moved from your wallet, you can begin contributing to the network with POS. At that moment your wallet will begin to have a % chance of minting which will be reflected in the official “minting view” tab on the faircoin wallet.

Wallets with the most faircoins are likely to find a block faster. Another factor affecting the chances of finding blocks is the concept of “age”, which makes minting probability grow each day after day 21, up to day 90.

Notice that once you discover a new transaction block, its minting status is set back to 0 and the process starts over. We could go on explaining, but the best way to learn is to download the wallet and start experimenting with your faircoins.

FairCoin V2 White Paper

- DRAFT

- Document version 1.0

- Thomas König, May 2015

- tom@fair-coin.org

- To comment on this draft paper, please visit FairCoop's FairCoin 2 Forum

FairCoin is the monetary base system for FairCoop The Earth Cooperative for a Fair Economy (see https://fair.coop). In FairCoop we develop tools and transfer knowledge that enable everybody to participate in a fair global economy. The existing version of the FairCoin wallet relies on mining and minting technology to secure the block chain. The problem is that neither mining nor minting can truly be considered fair, because both confer an advantage on the already rich. Therefore we decided to create a new version of FairCoin which corrects these issues.

With FairCoin2 (in short FC2) we can create block chain-based software that is fair, secure and power-saving. It is based on cooperation and not on competition.

It is built on the code-base of a recent version of the Bitcoin core client. This enables us to benefit from the latest developments made by the dedicated Bitcoin developers. Also the comprehensive infrastructure that already exists around Bitcoin can be adopted for FairCoin with minimal effort.

This document describes the design concepts we have implemented in FairCoin2. Some knowledge about how Bitcoin works is required to fully understand the contents of this document. The first paragraphs provide a rather high-level view of the FC2 concept and the further you read the more technical and detailed it becomes.

Overview

In contrast to other cryptocurrencies FC2 does not implement any mining or minting (aka. staking)functionality, which are both competitive systems. Block generation is instead performed by so-called certified validation nodes (in short CVN). These nodes cooperate to secure the network. To run a CVN one needs to complete a certification procedure which is called node certification procedure (in short NCP) that is operated by FairCoop (https://fair.coop/node-certification-procedure/). The requirements to operate such a node are described in chapter 3.1. Please note that definition of the NCP is out of the scope of this document and will be defined in a separate document. In the long run the NCP should be powered by a reputation system.

There is no reward for block creation (no coinbase/stake transaction). Therefore the money supply does not change over time and is fixed at the time we migrate to FC2. Nevertheless, the transaction fees go to the respective block creators to compensate their efforts for running a CVN.

Certain chain parameters, e.g. the transaction fee will be dynamically adjustable (without the need of releasing a new wallet version) by democratic community consensus. The FairCoin team needs the approval (digital signatures) of a high percentage of all the active CVN.

Block generation

Block generation takes place in a collaborative way. All CVN work together to bundle pending transactions into transaction blocks. These blocks can only be created by CVN every 3 minutes. Which CVN will generate the next block is determined by its time-weight. The time-weight describes how much time has passed since a CVN created its last block. If for example CVN A created a block 50 blocks ago and CVN B created it 55 blocks ago CVN B will be chosen to create the next block in the network. There can always only be exactly one CVN with the highest time-weight. If a new CVN joins the network for the first time it will be elected to create the next block. Between two locks only one new CVN can join in.

Block generation is performed in 3 phases. New transactions are accepted during all these phases.

Transaction accumulation phase

In this phase all nodes relay transactions they receive from other nodes to any node they are currently connected to. This phase lasts at least 170 sec. If there are no pending transactions in the network it takes as long as the next transaction hits the network. In other words, this phase only ends when there is at least 1 pending transaction in the network.

Time-weight announcement phase

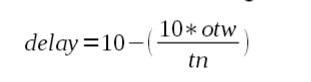

In this phase each CVN determines its own time-weight based on the local block chain information and announces it to all other connected nodes. Announcement messages are relayed by all nodes just like transactions. The higher the nodes time-weight the sooner the announce message is sent to the network according to the following simple formula:

Where:

delay is the time in seconds to wait before a CVN sends its own time-weight otw is the CVN calculated own time-weight tn is the total number of active nodes 10 is the constant of ten seconds, which is the duration of this phase

This will greatly reduce the amount of announcement packets sent over the network because if a CVN receives and correctly validates a time-weight announcement message from an other node with a higher time-weight it will not send its weight to the network.

Every CVN verifies that each time-weight announcement it receive is correct using the local block chain data (bogus announcements are discarded and a DoS ban score of 50 is proposed).

Time-weight announcements are used to determine the node with the highest time weight that is currently connected to the network.

This phase starts 10 sec. before the actual block target time.

Block creator election phase

This phase starts right after the Time-weight announcement phase. Every CVN determines the CVN with the greatest time-weight according to the announcements it received. It then signs and sends their candidate vote message to the network, which is relayed by every node just like transactions.

This phase has no defined length. It stops once the elected CVN has received enough vote messages for its own id from over 90% of all active nodes. This is the point in time when the collaboratively-elected CVN finally creates the next block in the chain containing all pending transactions from the so called “rawmempool”. Also parts of the signed vote messages are incorporated into the block to prove that optimally 100% but at least 90% of all active connected nodes agreed on the elected CVN.

Certified validation nodes (CVN)

The aim of the CVNs is to secure the network by validating all the transactions that had been sent to the network and put them into a transaction block chain. Blocks are created each 3 minutes (180 sec.). Transactions are confirmed after they have been added to a block. If there are no pending transactions no further blocks are created, which will not happen anymore after FairCoin has been widely adopted.

A CVN is a standard FairCoin core client configured with additional information namely certification data issued by FairCoop which “upgrades” it to a CVN. Every node will be assigned a unique id.

Requirements for running a CVN:

Every entity running a CVN must agree upon the following technical requirements and must carry the responsibility to full fill these rules.

- The system must be connected to the Internet all the time (24/7) and the TCP port 46392 must be reachable by all remote nodes from the Internet

- The system must use a public NTP server to synchronize its system time to, preferably pool.ntp.org to ensure that the system time is always correct

- The entity must have an account at the FairCoop web site

- The wallet software must be configured with certification data issued by FairCoop

Further requirements might be defined after public discussion. But this will be subject to the NCP document.

Node certification

But why would we need certification at all? A decent certification procedure ensures that a high percentage of all CVNs are honest creator nodes. At the moment the author sees no easy way of ensuring that each node has only one identity without a well established reputation system. If every node was a creator node a skilled attacker could modify the client software in such a way to create thousands of different identities and could then perform numerous different attacks against the network.

Transaction fees

The transaction fees go to the node which created the block. Transaction fees exist to avoid block chain spam and give block creators a small reward for taking the effort to leave their node running and pass through the certification procedure.Fees should be dynamically adjustable to satisfy any change in the value of FairCoin

Discussion

FairCoop's plan with the FairCoin distribution

Enric Duran:

" FairCoins was distributed before the idea of FairCoop even existed. Someone created this cryptocoin as well as the 50M Faircoins and spread it to all person that find it out in a airdrop… So all faircoins were distributed equally between cryptocurrency aficionados or people that find it out somehow…

After that, when the idea of FairCoop started to born, the initiators and other related people started to buy this faircoins by the rules of cryptomarket… So we started to collect all this coins with the objective to put it after in common projects…

The 20% you mentioned is in the fairFunds… This funds objective its to be re-distributed among all projects for the commons that needs financial aid… Also other 20% its between ppl and collectives compromised with the faircoop principles that also had bought faircoins to support the project and is committed with the cause, therefore in an autonomous way it will be also funding for projects related to the commons.

The remaining % is unknown where it is, however thanks to the http://coopfunding.net we aim to facilitate everyone to contribute in buying more of this coins and grow the FairCoop funds.

From the promoter team we encourage everyone to take part of the faircoop project by either giving a donation to the funds or if they have already some ideas for common projects to buy themselves faircoins.

We can not expropriate all dollars or euros or bitcoins.. But what we can do is to buy as peers as much as we can of this faircoins, and then participate in growing its value, increasing its market cap, and RE-distributing it between all projects for the commons

Thus, the plan is that: we are not gona distribute an “alter coin” we are gona take a coin, grow its value and re-distribute wealth iequitable in the real world.." (https://fair.coop/groups/faircoop-community/ask-us-anything/forum/topic/equitable-distribution-of-fair-coins-what-is-the-plan-to-achieve-this/#post-1857)

FairCoop project: why buy an existing cryptocurrency?

Enric Duran:

"Why choose to take advantage of an existing cryptocurrency such as Faircoin?

For a cryptocurrency to be accepted in cryptocurrency markets and be able to be bought and sold–exchanging it, for example, for Bitcoins–it must have a clean launch, which is to say, it must have been previously published so that all can participate. Another much-valued aspect is that the initiators of the cryptocurrency do not retain a significant portion of the cryptocurrency, or else it would be considered a scam.

If we were to distribute the cryptocurrency from the outset among the collectives that filled out a form and met certain criteria, it might seem quite fair outside the cryptocurrency community,, but inside we could easily find ourselves up against boycotts and complaints for having distributed it among our colleaguesusing political criteria , etc.

If, to avoid this situation, we were to allow a large percentage to be distributed by conventional criteria (mining it for several days, with a random list anyone can sign up for, etc.), we’d end up with minorities from the North making personal profits from our project, in a framework of speculation (because of the project we would be presenting). This could increase more quickly the value of what we defend, leading to drops in price which would create confusion, etc.

In contrast, if we take advantage of a cryptocurrency that has already been created and has already been through this initial speculative phase, is currently devalued, and on its way to being abandoned (right now, Faircoin is ranked at number 200, with a total value of 50,000 dollars; that is, with 500 dollars, we can buy 1% of all coins), it will be very easy for us to obtain an important share by means that are completely accepted by the cryptocommunity: buying it on the market for next to nothing. This way, we will be able to create a very advantageous situation for our project without having to assume the delicate responsibility of creating and distributing the cryptocurrency from the beginning.

Besides, it shouldn’t be difficult to ensure that once the dissemination of the project has begun and it is generating the ability to purchase and accumulate the currency, we can bring about a general trend toward a rising value of Faircoin, boosting the credibility of the project."

Discussion 2

Critical Evaluation of FairCoin as a cooperative currency

Oliver Sylvester-Bradley:

"FairCoin is one of the more ethically minded alternative currencies, which aims to “implement fair value exchange on a global level” using a unique “proof-of-cooperation mechanism”. Again, this is a blockchain based system but one which uses “collaboratively validated nodes” (CVNs) to secure the network. It’s a clever system but one which is still prone to speculation which undoubtedly undermines their proud claim that “FairCoin now is the the most ecological and resilient cryptocurrency”! Since their “air drop” (basically, dumping a load of coins around the internet to be picked up by whoever gets there first, with some limitations on claims per person) the “value” of a Faircoin has increased hugely and the community “claims” one Faircon is now worth €1.2. These claims about Faircoins’ value must be decided at a General Assembly via “consensus reached through an open, participatory process of discussion. Not the invisible hands of the market…” and the other Fair ventures like the marketplace and their growing community of local nodes do make this a valid and vibrant economy. But since everyone involved in Faircoin obviously has a vested interest in its increasing valuation and since Faircoin can be traded on at least two exchanges it is just as prone to speculation as gold, or Bitcoin. In fact, their page on “value” includes a slightly humorous request for speculators to leave Faricoin alone: “If you just want to get rich soon and intend to “pump and bump” – please consider other AltCoins to speculate on.” Not the most robust means of securing a stable, inflation and speculation proof system!"

(https://open.coop/2018/01/25/co-op-coin-ico-look-like/)

Why Did FairCoin Fail

Sam Dallyn, Fabian Frenzel:

"As the two valuations of FairCoin (the FairCoop valuation and the external cryptocurrency exchange price) diverged in 2018, FairCoop was faced with increasing pressures around the limited resource of capital, in the form of the Euro—the dominant government fiat currency in the regions where FairCoin was most widely used. The key concepts through which we analyse this problematic are the notion of commons boundaries (Ostrom 1990) and De Angelis’ (2017a, 2017b) conception of a “filtering membrane”. We argue that postcapitalist commons need clear boundaries to be protected from the encroachment of the values and practices of capital, which are centred around state backed fiat currency (De Angelis 2017a:313) and private value extraction from the commons. Yet because some capital is necessary to sustain the commons, a “filtering membrane” (De Angelis 2017b:228–229) is required for the postcapitalist commons to be sustainable. The “filtering membrane” is a selective filter which is intended to secure capital for certain items that cannot be acquired internally within the commons (such as electricity and heating), but with certain boundaries to prevent the erosion or weakening of the shared (postcapitalist) values of the commons itself. While capitalism, as Gibson-Graham (2006:198) characterise it, is an “exploitative class process in which surplus labor is appropriated from the direct producers in value” by nonproducers, who in this process appropriate capital. Capital here is intimately connected with state backed fiat currency, since we have a system of privatised money creation in which commercial banks generate money by lending it at interest (Mellor 2010).

Two principal research questions frame the following investigation: First, is FairCoop and FairCoin a viable postcapitalist commons and cryptocurrency that is sustainable? For De Angelis (2017a:122) sustainability means the establishment of a “series of stock-flow relations necessary to (re)produce” the commons (emphasis added), through a structure determining the extraction of limited resources (see De Angelis 2017a:167; Ostrom 1990:33). If limited resources are extracted excessively in a way that outpaces their inflow into the commons, the reproduction of the commons is endangered. Second, what can FairCoin and FairCoop tell us about the potential to generate scalable postcapitalist commons? Being scalable means the extent to which the commons can spread beyond the specific site (Gerhardt 2020) potentially to multiple other sites and regions, and thus become trans-local in scale. As we will see the answer to the first question is negative for the reasons that emerge from the response to the second. FairCoop shows us that within postcapitalist commons, the boundaries between commons and capital need to be firmer in order to clearly limit the extraction of scarce resources (in this case state backed fiat currency). Thus, the principal contribution of this paper is to outline some additional commons boundary design principles that are necessary for postcapitalist commons to be scalable and sustainable. We develop a more extensive and radical conception of Ostrom’s (1990:90) first design principle of commons boundaries—principally for Ostrom the rights to withdraw resources and the boundaries around a shared resource—by using the limits of the FairCoop case to think through a firmer basis for more sustainable and scalable postcapitalist commons.

From the conclusion:

"In reflecting on the FairCoop and FairCoin case, the movement could be described as a failure in that the initial model of hacking the cryptocurrency markets to build and sustain a postcapitalist commons clearly did not work as planned. That said, as Chatterton (2016) argues, postcapitalist commons are often characterised by risk taking and experimentation, and a key feature of experimentation is that particular projects may not work out as intended; experimentation in short is also about the freedom to fail, provided of course that things can be learnt from what did not work. Furthermore, as Khasnabish and Haiven (2015:24) note, it is a mistake to evaluate social movements only by their stated objectives, since this ignores the ways in which they generate and sustain progressive and radical platforms of “social relationality and reproduction”, which can generate future, improved commons experiments. Furthermore, from the lack of sustainability that was evident in the FairCoop case we can take some important lessons in terms of future efforts to generate scalable postcapitalist commons through peer2peer technologies.

This paper has highlighted a tension between postcapitalist commons expansion and boundaries. If a postcapitalist commons expands too quickly without sufficient boundaries from capital, its relation to capital is likely to become unsustainable. While there are clearly limitations to deducing design principles in terms of postcapitalist commons boundaries from a close investigation of a single case, we nevertheless think this is worth attempting because of the importance and distinctiveness of FairCoop in making a rare attempt through FairCoin to generate a postcapitalist commons alternative that is scalable (Chatterton and Pusey 2020; Gerhardt 2020; Griziotti 2019).

Having said this, and subject to further research into future postcapitalist commons experiments attempting to scale, we think that from this case it is possible to outline some additional design principles in regard to postcapitalist commons boundaries:

- An economic model that is as resilient as possible to a divergent evaluation by capital and decreasing capital returns.

- A clear value framing in which the values around the maintenance of the commons are placed above private interests in securing capital, and this must be true for new participants as much as existing ones.

- Means to ensure that these commons principles are reflected in practices, we have suggested peer2peer reputational feedback as a potential way of doing this.

- There must be transparency and clarity around the accounting process in which all participants are aware of how limited capital resources are and potential risks arising from this.

Gerhardt (2020:696) argues that overcoming “the apparatus involved in the monopolisation of monetary value” is a key task in building postcapitalist commons, but clearly our investigation into the FairCoop case has shown the considerable challenges of doing this. What the case also highlights is the partiality of postcapitalist alternative currencies, in restaging the fiction of the dominant monetary system (Maurer 2003) without transcending it. This is arguably a feature of postcapitalist projects in general, in operating within, while trying to work towards an after, capitalism. That said, the postcapitalist peer2peer alternative currency space is an experimental and generative one with continuing different lines of flight (see for example Economic Space Agency 2020; Fairo 2019; Holo 2018) that potentially take us beyond the confines of site-specific commons alternatives (Gerhardt 2020). In suggesting some further design principles for greater boundaries from capital in postcapitalist commons, which we argue are necessary to be both sustainable and scalable, we hope to have made a contribution to rethinking and advancing this vibrant field of activist experimentation."

(https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/anti.12705)

FairCoin's failure to hack the market; how the market hacked the FairCoin commons

Sam Dallyn, Fabian Frenzel:

Hacking the Market? The Two Price Model

FairCoin was characterised by an unusual dual price structure. FairCoop and the community of activists around it make decisions about governance, values, and the adoption and development of software applications. Crucially, FairCoop general assemblies also established a FairCoop exchange rate at which goods and services were priced in FairCoin, and at which the exchange from FairCoin to Euros was promised for FairCoop participants and merchants (FairCoop 2019). Yet FairCoin can also be purchased on external cryptocurrency exchanges outside FairCoop. Crypto exchanges are a crucial feature of the cryptocurrency world since they are the principal means of acquiring cryptocurrencies in a competitive online bidding process. At different points FairCoin was listed on different cryptocurrency exchanges—the most high profile one being Bittrex, which it was delisted from in March 2018, after the community refused to name a CEO or fulfil certain regulatory requirements necessary to be classified as a security (FairCoin 2018).1 Because the price of FairCoin on these external exchanges was highly volatile, the exchange rate that was established by the general assemblies was seen as a way of protecting merchants and users from the volatility of cryptocurrency exchanges. It was meant to ensure that the price of goods and the value of FairCoin remained relatively stable within the postcapitalist commons. In addition, there was a mechanism for channelling capital into the commons: a rising value of FairCoin on external cryptocurrency exchanges would enhance the commons by increasing the relative value of FairCoin held by participants in FairCoop. The general assemblies would respond to the increasing value of FairCoin on external cryptocurrency exchanges by raising the agreed FairCoin-to-Euro exchange rate within FairCoop—which would be decided through consensus decision-making.

This brings us to the key problematic in our investigation of FairCoop and commons boundaries: How can capital be extracted and used for the good of the commons and its reproduction to the ends of “love, solidarity and conviviality” (De Angelis 2017a:339) in a manner that protects and supports the alternative that is being built? As Chris, based in Jura, noted to one of us, as a postcapitalist commons FairCoop sought to use FairCoin as a filter that: … would ideally be a membrane that interacts both with the capitalist system and with the Fair economy that is postcapitalistic or going towards postcapitalistic … That doesn’t mean that it completely 100% prevents capitalistic value extraction it just means that it prevents value extraction of capitalistic behaviour so that its more that you get a value benefit into the Fair economy.

The nature of the filtering membrane is that some things can filter through and not others (De Angelis 2017b:229), so that capital can be filtered into the commons, while “capitalistic value extraction” needs to be prevented from seeping into the internal values and practices of the commons itself. Such a boundary is always an unstable one and, as Chris notes, cannot be absolute, because the postcapitalist commons is necessarily in capitalism, while simultaneously seeking to retain autonomy and boundaries from it. Yet this highlights a key problem that faced FairCoop and FairCoin: FairCoin trading is essentially open and unrestricted on external cryptocurrency exchanges. To the extent to which there were any commons boundaries these were established through FairCoop; yet FairCoop itself had no membership and was essentially open. The only recognised boundary was that a couple of FairCoop participants would need to vouch for people before they could become involved in governance and core tasks within the commons. So, in effect FairCoin had no boundaries around external trading and investment, while FairCoop had no membership and minimal commons boundaries in terms of who could participate.

Bauwens et al. (2019:7) describe the processes through which capital is filtered into the commons as one of “transvestment”. It should be noted that commons that are reliant on such strategies need to generate capital and returns to be sustainable. As a transvestment strategy, FairCoop sought, ultimately unsuccessfully, to use FairCoin’s cryptocurrency exchange market value as a means to extract capital. FairCoin could be purchased and exchanged for goods and services at a set internal community FairCoop rate, decided via consensus in online general assemblies; but external cryptocurrency exchanges also presented opportunities to trade FairCoin for different cryptocurrencies (primarily Bitcoin) where its value was far more volatile and subject to the decisions of cryptocurrency traders and investors.

The initial, overly optimistic, model was based on the premise that the appreciating cryptocurrency exchange market price could be hacked to sustain and further the postcapitalist commons, by selling or buying FairCoin on cryptocurrency exchanges. As one anonymous interview respondent explained, it: … was about creating a commons … so that value shifts from private property to the commons, this was also connected to the hack of the markets so that money from the capitalistic market can flow into something like FairCoin and can be extracted for the common good.

This has some resonances with Wark’s (2004:§034) conception of hacking in which there is the generation of “new abstractions” through breaking into “the abstraction of property” and overcoming its limitations (Wark 2004:§036). But as Wark (2004:§081) also notes, the hacker class “has a tactical interest in the representation of the hack as property, as something from which a source of income may be derived”, in this case FairCoin as property. Such hacking is often limited to specific public interventions, or momentarily breaking into a given private configuration of information, assets, or property, as was the case with Duran’s actions against the banks in 2008. It is not clear how it can forge a durable strategy to sustain the needs of a postcapitalist commons indefinitely; since capital is likely to change its approach to guard against future hacks.

The appreciation of FairCoin’s exchange value on external cryptocurrency exchanges in 2016–2017 coincided with the expansion of the movement through the creation of different FairCoop local nodes. However, this external market valuation ultimately mirrored Bitcoin’s volatile price on different cryptocurrency exchanges, which entered a boom phase in the late months of 2017, only to fall from around $19,000 per Bitcoin at its height in December 2017 to below $4000 in October 2018 (Ouimet 2019). FairCoop’s internal community exchange value rose up to 1.2 Euros to reflect its rising value on cryptocurrency exchanges in January 2018. But, like Bitcoin, its value on cryptocurrency exchanges dropped dramatically in the ensuing months and (unlike Bitcoin) did not subsequently recover. Due to the need for consensus within general assemblies and a series of internal disagreements, the community price was not subsequently lowered with the drastic cryptocurrency exchange market price drop.

The divergence between the two FairCoin prices led to increasing bifurcation and division within the FairCoop community. Guy, based in Spain, was involved in the Peer2Peer Social Organization group—a group of researchers reporting on peer2peer and open source alternatives. Guy worked on developing the original WordPress FairCoop site when visiting Enric Duran in hiding in 2014, and has subsequently collaborated with FairCoop on and off, while also being constructively critical of the dynamics that have unfolded. As he noted: There’s really two types of people who are interested in FairCoop and FairCoin. It’s the people who basically bought a load to speculate that’s their primary focus and they want it to be fair as well … [and] there’s the other people who don’t care at all about the speculation they want it to be just the official price and they just want to buy and sell at the official price … So, then it’s kind of stuck because you need a consensus.

Some communities within FairCoop felt that the commons should hold firm and ignore the drop in cryptocurrency exchange market price, on the basis that the FairCoop commons itself could guarantee the fixed higher exchange rate of 1.2 Euros by continuing to offer goods and services internally (Duran 2018). But commitments had been made by FairCoop to exchange FairCoin back to Euros at this rate (FairCoop 2019). For FairCoop, which has no official membership, there was no clear way to prevent people from taking advantage of price differences via arbitrage. The problem of arbitrage is less pressing for exchanges at smaller scale, such as a daily supply of fruit and vegetables purchased in FairCoin from a committed FairCoop merchant. But arbitrage generated a clear loss for FairCoop if someone bought cheap FairCoin from cryptocurrency exchanges and then bought goods with these FairCoin, and the merchant then asked FairCoop for their FairCoin to be exchanged back to Euros at the higher, official FairCoop exchange rate. This problem of arbitrage was extenuated by the selling of certain high-end technological products in FairCoin, particularly electric bikes. These bikes were priced in FairCoin at the higher rate of 1.2 Euros-a-FairCoin. The merchants selling these bikes then asked FairCoop to exchange these FairCoin into Euros at the 1.2 Euro rate, as promised (FairCoop 2019). But these FairCoin could easily have been acquired by consumers from external cryptocurrency exchanges at a fraction of the cost, such as 0.11 Euros-a-FairCoin, which was FairCoin’s cryptocurrency exchange market price on 19 March 2020 (FairPlayGround Statistics 2020). The expectation that FairCoop could continue to exchange FairCoin for Euros at the 1.2 Euros-a-FairCoin rate was clearly unsustainable, and this problem of arbitrage gives rise to the broader issue of convertibility.

Convertibility: Due to the commons itself not having any clear formal boundaries, for example through a membership structure, two increasingly divergent ways of valuing FairCoin existed in the same commons. For some participants in FairCoop the external cryptocurrency exchange market price had greater importance than FairCoop’s official community price. The divergence between the two prices became a problem because of the commitments in place at that time for FairCoop to meet the exchange of FairCoin to Euros for up to 1000 Euros per month for active FairCoop participants—which was subsequently reduced in 2019 (FairCoop 2019). This reflects FairCoop and FairCoin’s ambiguous status as a postcapitalist commons and a tradeable cryptocurrency, which while seeking to build an alternative economy based on shared values, also sought to offer a guaranteed rate of exchange in Euros. FairCoop itself aimed to hack cryptocurrency exchanges to generate Euros but was not clearly bound from them. In the sense that FairCoop participants, actors leaving the FairCoop commons, or people unaffiliated with FairCoop, were free to sell or buy large quantities of FairCoin for Bitcoin on external cryptocurrency exchanges.

This also highlights a wider question of convertibility and the relation to Euros, despite the efforts to generate an alternative to state backed fiat currency. Pilikum—an activist based in Coruña, a region of Spain that had considerable success in encouraging merchants of different kinds to use FairCoin, including a hairdresser, a pub, an organic food shop and a range of other producers—reflected on these experiences: If we are going to a shop, this is a familiar shop they are trying to survive, a couple and two children and they are just like fighting to earn some money. And I told them you can spend your FairCoin in this shop that sells ecological food but this is so expensive, when FairCoin was going up in value it was easy to say that, now it’s not the same, so for them it’s easier to change to Euros and buy cheaper food.

The Euro has often assumed the position of an inescapable backdrop in FairCoop discussions, debates and practices. In alternative currencies the quantitative operation of equivalence in the dominant state backed fiat currency is not one that is ever really transcended (see Maurer 2003; Ould-Ahmed 2010). Maurer (2003:334) argues that alternative currencies function like a mouse trap in that they artificially restage the social relation, not in terms of ever doing away with government backed fiat currency; but in staging the fiction differently. The restaging of social relations of exchange involves generating different sites in which an alternative currency is exchanged, and state backed fiat currency is not used. For example, an individual may buy a beer from the bar of a social centre in Milan, or Jura, or Athens, and make the purchase in FairCoin. The person at the bar accepts the FairCoin on the basis of shared political values centred on the ideals and values of FairCoop as a postcapitalist commons. In this exchange the fiction that state backed fiat currency is necessarily the true equivalent of value—a fiction that conceals the social relations of production and (re)production that generate the exchange (Maurer 2003:332–333)—is restaged through a different token of exchange which reflects different values. The similarity with the mousetrap for Maurer (2003:334) is that in laying the mouse trap you artificially restage the scene of the crime in which the mouse captures the piece of food. The key analogy is not in the catching of the mouse but in the laying of the trap, in setting up the social relation of exchange; but on this occasion an alternative currency will be exchanged. FairCoop had an additional (more ambitious element) which meant that FairCoin was intended to function more like a cat, the idea was to capture and utilise the capital inflow from external cryptocurrency exchange trading of FairCoin, to generate capital from external markets to support FairCoop as an expanding commons. In other words, it assumed an increasing inflow of capital into the commons from a rising cryptocurrency exchange market value of FairCoin, to sustain FairCoop’s expansion. The functioning of the commons itself became dependent on an increasingly favourable valuation of FairCoin by capital, a problem that—as we will see—was compounded by insufficient commons boundaries."

(https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/anti.12705)