PART ONE: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

The first is the classic capitalist economy based on labor value and proprietary forms of knowledge, which dominated the industrial phase of capitalism. The value model of the traditional proprietary capitalism is based on the premise of workers creating value in their private capacity as providers of labor (figure 4). This value is captured and realized in the market by capital, which dominates the extraction of surplus value. In the old neoliberal vision, the state becomes a market state protecting the privileged interests of property owners; and civil society is a derivative rest category, as is evidenced in the use of our language (non-profits, non-governmental). This form is characterized by the deskilling of workers' previous artisanal production knowledge, now codified in the production process itself, where labor becomes an appendage to the ecosystem of machines. In this division between labor and capital, managerial and engineering layers manage collective production on behalf of the owners of capital, which is at first largely industrial capital, though financial capital rapidly rises to prominence. The codified knowledge is proprietary and the value is increasingly captured as intellectual property (IP) rent. Industrial profit, based on the direct extraction of surplus value, is the dominant form of value capture however, and there is partial redistribution in the form of wages. | The first is the classic capitalist economy based on labor value and proprietary forms of knowledge, which dominated the industrial phase of capitalism. The value model of the traditional proprietary capitalism is based on the premise of workers creating value in their private capacity as providers of labor (figure 4). This value is captured and realized in the market by capital, which dominates the extraction of surplus value. In the old neoliberal vision, the state becomes a market state protecting the privileged interests of property owners; and civil society is a derivative rest category, as is evidenced in the use of our language (non-profits, non-governmental). This form is characterized by the deskilling of workers' previous artisanal production knowledge, now codified in the production process itself, where labor becomes an appendage to the ecosystem of machines. In this division between labor and capital, managerial and engineering layers manage collective production on behalf of the owners of capital, which is at first largely industrial capital, though financial capital rapidly rises to prominence. The codified knowledge is proprietary and the value is increasingly captured as intellectual property (IP) rent. Industrial profit, based on the direct extraction of surplus value, is the dominant form of value capture however, and there is partial redistribution in the form of wages. | ||

[[File:4._Traditional_proprietary_capitalism_copy.png|490px]] | |||

Often, once a social (labor) movement takes form and becomes powerful and influential, the state redistributes taxable wealth to the workers as consumers and citizens in the form of social provisions (pensions, unemployment benefits, health care reimbursements, and so on). This happened extensively during the period 1945-80 as manifested by the rise of the welfare state and Keynesian policies, especially in the western world. Since 1980, under contemporary conditions of labor weakness in the de-industrializing developed countries, the state has been redistributing the wealth to the financial sector and creating conditions of debt dependence for the majority of the population. In this neoliberal format, which became dominant after 1980 and before the emergence of civic peer networks in the eve of 21st century (Benkler, 2006; Bauwens, 2005), the part of labor became stagnant and most of the value streamed towards financial capital. The credit system developed into an increasingly important means to maintain the fictitious buying power of consumers and, therefore, the primary means of surplus realization, through debt dependency and servicing. | Often, once a social (labor) movement takes form and becomes powerful and influential, the state redistributes taxable wealth to the workers as consumers and citizens in the form of social provisions (pensions, unemployment benefits, health care reimbursements, and so on). This happened extensively during the period 1945-80 as manifested by the rise of the welfare state and Keynesian policies, especially in the western world. Since 1980, under contemporary conditions of labor weakness in the de-industrializing developed countries, the state has been redistributing the wealth to the financial sector and creating conditions of debt dependence for the majority of the population. In this neoliberal format, which became dominant after 1980 and before the emergence of civic peer networks in the eve of 21st century (Benkler, 2006; Bauwens, 2005), the part of labor became stagnant and most of the value streamed towards financial capital. The credit system developed into an increasingly important means to maintain the fictitious buying power of consumers and, therefore, the primary means of surplus realization, through debt dependency and servicing. | ||

Revision as of 19:08, 23 March 2014

This entry is about the forthcoming book "Network Society and Future Scenarios for a Collaborative Economy" co-authored by Vasilis Kostakis and Michel Bauwens. The scholarly book will be published by Palgrave Macmillan and here you may find a working draft of the part one.

We invite everybody to read and comment on its contents by i) using the relevant discussion wikipages; and/or ii) sending a personal email: kostakis.b AT gmail.com.

<=Contents and Preface || Next part=>

Capitalism as a creative destruction system

The capitalist mode of production has arguably created a political economy prone to crises. Following Harvey's vivid narration (2013: 5) of a capitalist's life, his typical day begins with a certain amount of money and ends with a lot more. The next day, however, the capitalist has to think of how he is going to manage the surplus capital: will he reinvest the profits or will he spend them? In case we are not speaking about monopolies (Sweezy and Baran, 1966), the fierce competition makes him reinvest, because if he does not, a competitor certainly will. Of course, a successful capitalist profits enough to keep himself into the profitable expansion while he lives a super-luxurious life. The constant search for new terrains of growth is a premise for the sustainability of the system. The capital accumulation has to expand at a compound rate: “the result of perpetual reinvestment is the expansion of surplus production”, Harvey writes (2013: 5). The capitalist faces various problems during the aforementioned procedure. For instance, if the wages are too high due to a scarcity of labor, in order to keep the system in a growth trajectory, either new fresh labor forces have to be found or precarious conditions of living have to be artificially created and, thus, drop wages. Further, when new means of production along with technological and/or organizational innovations are introduced, the terrains of growth are enriched. New needs and wants are defined, the distances among nation-states diminish and the capitalist is capable not only of finding new natural resources but also of attracting new consumers (Harvey, 2013, 2010; Perez, 2002). When the purchasing power cannot serve an increasingly expanding economy, new credit-based financial instruments are invented. Sometimes if the profit rate is low, companies would merge and create powerful conglomerates and, therefore, monopolies. If the capital accumulation still does not keep up, then the system falls into a serious crisis. Capitalists are unable to find profitable paths of reinvestment; capital accumulation stagnates and its value decreases. Massive unemployment, impoverishment and social turmoils can be some of the consequences of a capitalist crisis.

However, many would argue that no other economic system has produced so much wealth. On the other hand, some might claim that no other system has produced so much destruction. Others consider capitalism as a creative destruction system. This book uses the theory of techno-economic paradigm shifts (TEPS) – gradually developed by Schumpeter (1982/1939; 1975/1942), Kondratieff (1979), Freeman (1974; 1996), and in particular Perez (1983; 1985; 1988; 2002; 2009a; 2009b) – as its point of departure to develop its narrative. This choice arguably helps recognize the dynamic and changing nature of the capitalist system in order to avoid any particular period extrapolation as “the end of history” in the fashion of Fukuyama (1992). Therefore the aim is not to make capitalism crisis-free but to manage crises and soften blows. In other words, to make a successful “creative destruction management” (Kalvet and Kattel, 2006), maximizing its creative power while minimizing its destructive force (Mulgan, 2013). One should be aware of many other theoretical alternatives, such as the Marxist ones, in understanding and acting within certain social, technological and economic processes. It would be interesting to mention that both Marxist and neo-Schumpeterian theoretical approaches consider capitalism prone to crises which are basic features of its normal functioning. However, the neo-Marxist critique (see Wolff 2010; Harvey 2007; 2010) puts emphasis on the inherent unsustainability of capitalism aiming at a different system – “modern society can do better than capitalism”, Wolff (2010) postulates – whereas neo-Schumpeterians, such as Perez (2002) or Freeman (1974; 1996), see crises as a chance to move the capitalist economy forward. The take of this book is integrative trying to highlight the potential of new modes of social production and organization which are immanent in capitalism but, in the long term, might be transcendent to the dominant system.

If we follow Schmoller (1898/1893), the main figure of the German Historical School, history is the laboratory of the economist. Despite the unquestionable uniqueness of each historical period in the socio-economic development, the theory of TEPS accepts recurrence as a frame of reference and, having each period’s uniqueness as the object of study, tries to interpret the potential and the direction of change (Perez, 2002). Moreover, it embraces the Schumpeterian (1982/1939) understanding of economy as “an interdependent sequence of dynamic forces of change and static equilibrating forces” (Drechsler et al., 2006: 15). The essential fact about capitalism is the process of creative destruction which incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, destroying the old one, while it creates a new one (Schumpeter, 1975/1942). Each techno-economic paradigm (TEP) is based on a constellation of innovations, both technical and organizational, that are the driving force of economic development (Perez, 1983). Moreover, each TEP plays the central role in the recurring pattern of the cyclical movement: from gilded ages to golden ages; from an initial installation period, through a collapse and recession which signify the turning point, to a full deployment period (Perez, 2002; 2009a). Therefore, in the Perezian framework (2002; 2009a), progress in capitalism takes place by going through various successive great surges of development which are driven by successive technological revolutions. Each of these overlapping great surges of development, which lasts approximately 40-60 years, is the process by which a technological revolution and its paradigm propagate across the economy, “leading to structural changes in production, distribution, communication and consumption as well as to profound and qualitative changes in society” (Perez, 2002: 15).

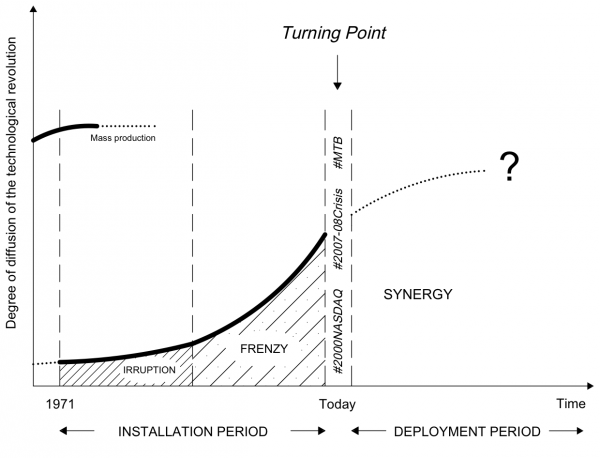

According to the TEPS theory, during the last three centuries the world has experienced five technological revolutions: the first industrial revolution based on machines, factories and canals (initiated in 1771; birthplace: Britain); the age of steam, coal, iron and railways (1829; Britain); the age of steel and heavy engineering (1875; Britain, USA, and Germany); the age of automobile, oil, petrochemicals and mass production (1908; USA); and the age of information technology and communication (1971; USA). Each of these processes evolved “from small beginnings in restricted sectors and geographic regions”, and ended up “encompassing the bulk of activities in the core country or countries and diffusing out towards further and further peripheries, depending on the capacity of the transport and communications infrastructures” (Perez 2002: 15).

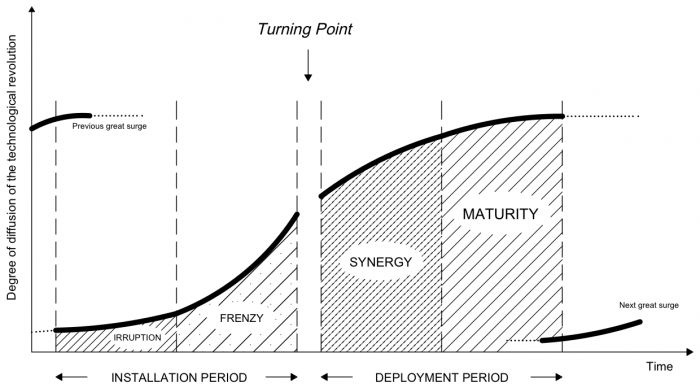

A great surge of development consists of four phases, which, although not strictly separated, can be identified as sharing common characteristics throughout history (figure 1).

Firstly we have irruption (technological explosion) that is the initial development of the new technologies in a world where the bulk of the economy is made of old, maturing and declining industries; then frenzy follows, which is a very fast development of technology that needs a lot of finance (this is when the financial bubbles are created). These two first phases constitute the installation period of the new TEP, when finance and greed prevail and the paper economy decouples from the real one. Next, turbulent times come (that is, collapse, recession and instability) in what Perez calls the turning point, which is neither a phase, nor an event but a process of contextual change where the institutional changes for the deployment period of the newly installed paradigm take place. A lot of institutional innovation occurs and economies are enabled to take full advantage of the new technology in all sectors of the economy and to spread the benefits of the new wealth creating potential more widely across society. These synergies appear in the early stage of deployment (synergy phase) until they approach a ceiling (maturity phase) in productivity, new products and markets. When that ceiling is hit, there is social unrest and confrontations while the conditions are being set for the installation of the paradigm which will be based on the next technological revolution.

Perez (2009b) brings to the fore the special nature of major technological bubbles (MTB), which are endogenous to the process by which the society and economy assimilate each great surge. The MTB tend to take place along the diffusion path of each technological revolution: from the installation period, when the new constellation of technologies is tested and investment is defined by the short term goals of financial capital (so a rift between real values and paper values occurs), to the deployment period, when the financial capital is brought back to reality, production capital takes the lead and the state is called to make effective “creative destruction management” (Kalvet and Kattel, 2006). Perez (2009b) argues that the MTB of the current TEP, that is the information and communications technology (ICT) revolution, occurred in two episodes (figure 2).

First was the Internet mania, based on technological innovation, which ended in the NASDAQ collapse in 2000; followed by the easy liquidity bubble, based on financial innovations accelerated by the new technologies, which ended in the financial crisis in 2007-8. The essential implication of Perez’ argumentation (2009b: 803) is that “what we are facing is not just a financial crisis but rather the end of a period and the need for a structural shift in social and economic context to allow for continued growth under this paradigm”. Moreover, Perez’ essay (2009b) on the double bubble, aligned with the TEPS theory, is used as a point of departure that treats the current situation as not just another passing recession, and sets the ground for tentative proposals concerning the second half of the ICT revolution’s wealth-generating potential.

After the almost 30 year-long paroxystic culmination, since the introduction of the microprocessor in November 1971 in California, of market experimentation and moments of Galbraithian irrationality (1993), we find ourselves in the aftermath of two major bubbles and arguably in the midst of a major capitalist crisis (Fuchs, Schafranek, Hakken, and Breen, 2010: 193). In other words, we are witnessing, as we will later see, the swing of the pendulum from the extreme individualism to the collective, synergistic well being with the whole system trying to recompose (Perez, 2002), while political unrest (for example the EU coherency crisis triggered by the debt crisis) and protests (from the Indignados movement in Spain and Greece to the Occupy Wall Street movement in the USA) are globally erupting. Though, this book's goal is neither to describe the strands and ramifications of the current crisis, as this has been done elsewhere (see Harvey, 2007; 2010; Chomsky, 2011; Funnell, Jupe, and Andrew, 2009; Stiglitz, 2010), nor to point the historical parallels of previous turning points within capitalism, as Perez has done that in detail in her 2002 book. It can be claimed, however, that the two bubbles at the turn of the century bring to mind the 1929 depression as they share one fundamental characteristic: the structural tensions within capitalism make the system, at least in its current form, unsustainable. The world is arguably at a crossroads where the excesses, the fallacies and the unsustainability of the current practices have to be recognized; appropriate regulatory changes have to be made where usual recipes to confront the tensions fail; and the conditions, where the production capital is put in control, greater social cohesion is achieved and the desperation and anger turn into creation, have to be facilitated (Perez, 2002; 2009a; 2009b). In other words the turning point is a time of indeterminate realization of the full potential of the current ICT-driven paradigm, creating the new fabric of the economy and overcoming the tensions that cause this premature saturation (Perez, 2002).

Beyond the end of history: Three competing value models

Have we already lived the end of history with the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989-90? Is the capitalist mode of production the final stage of human progress? Or are we currently living in the end times with capitalism approaching its terminal crisis? According to Žižek (2010, p. x), the dominant system is unable to face its internal imbalances and its failures: the ongoing ecological crisis as well as the emergence of new forms of apartheid, walls and slums. Capitalism transforms not because of its failures but because of its successes, neo-Schumpeterians might reply, and now it is high time we created virtuous circles of production that would allow the system to reinvent itself once again. The environmental crisis can be seen as an opportunity for investment and sustainable growth (Gore, 2013). In the meantime, a new type of capitalism, named “cognitive capitalism”, arises in which “the object of accumulation consists mainly of knowledge” that is now the basic source of value (Boutang, 2012: 57). The industrial mode of production is becoming obsolete and the “network” is the main pattern of organizing production and socio-political relations (see only Castells, 2000; 2003; 2009). Peer-to-peer (P2P) technologies and renewable energy merge creating an energy Internet and, thus, inaugurate a third industrial revolution (Rifkin, 2013). On top of that, one may add another disruptive technological cluster, the “Internet of Things”, which could help “humanity reintegrate itself into the complex choreography of the biosphere, and by doing so, dramatically increases productivity without compromising the ecological relationships that govern the planet” (Rifkin, 2014: 13). Others (see Anderson, 2012) point to the emerging desktop manufacturing technologies, such as the three dimensional (3D) printing, and consider them as the pervasive technological cluster which will trigger a new industrial revolution. Succeeding in taking advantage of these transformations, and, at least in theory, the benefits of the new wealth creating potential will spread more widely across society.

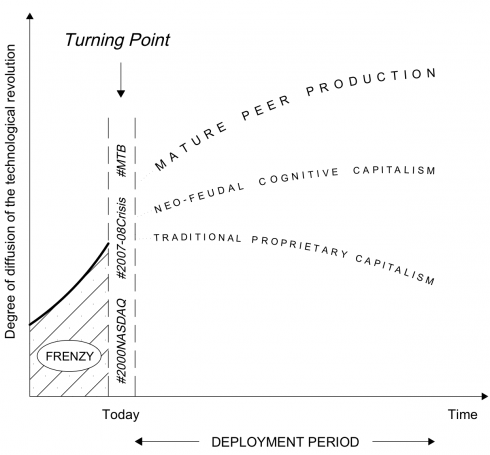

At the current turning point of the ICT-based TEP and within the present political economy, this book argues, there are three different value models competing for dominance which influence the way that the institutional recompositions will take place. One form is still dominant, but rapidly declining in importance; a second form is reaching dominance, but carries within itself the seeds of its own destruction; and a third is emerging, but needs vital new policies in order to become dominant (figure 3).

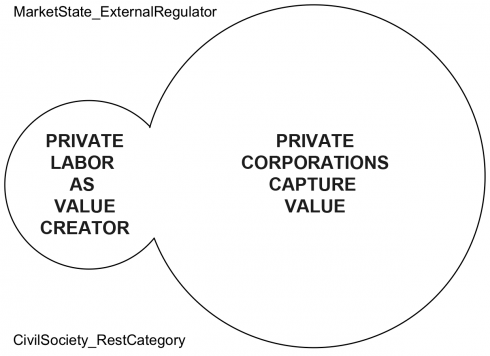

The first is the classic capitalist economy based on labor value and proprietary forms of knowledge, which dominated the industrial phase of capitalism. The value model of the traditional proprietary capitalism is based on the premise of workers creating value in their private capacity as providers of labor (figure 4). This value is captured and realized in the market by capital, which dominates the extraction of surplus value. In the old neoliberal vision, the state becomes a market state protecting the privileged interests of property owners; and civil society is a derivative rest category, as is evidenced in the use of our language (non-profits, non-governmental). This form is characterized by the deskilling of workers' previous artisanal production knowledge, now codified in the production process itself, where labor becomes an appendage to the ecosystem of machines. In this division between labor and capital, managerial and engineering layers manage collective production on behalf of the owners of capital, which is at first largely industrial capital, though financial capital rapidly rises to prominence. The codified knowledge is proprietary and the value is increasingly captured as intellectual property (IP) rent. Industrial profit, based on the direct extraction of surplus value, is the dominant form of value capture however, and there is partial redistribution in the form of wages.

Often, once a social (labor) movement takes form and becomes powerful and influential, the state redistributes taxable wealth to the workers as consumers and citizens in the form of social provisions (pensions, unemployment benefits, health care reimbursements, and so on). This happened extensively during the period 1945-80 as manifested by the rise of the welfare state and Keynesian policies, especially in the western world. Since 1980, under contemporary conditions of labor weakness in the de-industrializing developed countries, the state has been redistributing the wealth to the financial sector and creating conditions of debt dependence for the majority of the population. In this neoliberal format, which became dominant after 1980 and before the emergence of civic peer networks in the eve of 21st century (Benkler, 2006; Bauwens, 2005), the part of labor became stagnant and most of the value streamed towards financial capital. The credit system developed into an increasingly important means to maintain the fictitious buying power of consumers and, therefore, the primary means of surplus realization, through debt dependency and servicing.

We argue that this value model of traditional proprietary capitalism, dominant in the installation period of the current TEP, is approaching its terminal point. Its inherent unsustainability is manifested in a twofold problem. On the one hand, industrial capitalism considers nature to be a perpetually abundant resource, that is it is based on a false notion of material abundance in a finite world. On the other hand, the traditional, industrial version of cognitive capitalism enforces the idea that intellectual, scientific and technical exchange should be subject to strong proprietary constraints. In that way an artificial scarcity of knowledge is created subjecting innovation to legal restrictions and allowing for profit maximization and, hence, capital accumulation. Thus appears the paradoxical but also dramatic contradiction of the present, dominant system: while it is rapidly overburdening the carrying capacity of the planet, at the same time it inhibits the solutions that humanity might find for it. For example, the dramatic increase in patents has not been paralleled by an increase in technological innovation: “there is no empirical evidence that they [patents] serve to increase innovation and productivity, unless productivity [or innovation] is identified with the number of patents awarded” (Boldrin and Levine, 2013: 3). “In the long run”, Boldrin and Levine argue (2013: 7), “patents reduce the incentives for current innovation because current innovators are subject to constant legal action and licensing demands from earlier patent holders”. The process of innovation relies on building on former innovations, therefore the broader the pool of accessible ideas the more chances there are for innovation (Brynjolfsson and McAfee, 2011). To recap, this combination of quasi-abundance and quasi-scarcity destroys the biosphere and hampers the expansion of social innovation and a free culture, and this situation has arguably to be reversed.

The recent crises have brought scholars from various traditions and schools to agree that the global economy is currently at a turning point within the ICT-driven TEP. In this book, we deal with the remaining two competing value models which are more synchronized with the main characteristics of the current TEP, and seem to introduce less fragile alternative approaches for development in the deployment period. The second form is the neo-feudal cognitive capitalism, in which proprietary forms of knowledge are in the process of being displaced by emerging forms of peer production (Benkler, 2006; Bauwens, 2005), but under the dominance of financial capital. We will describe how this process is well under way. The third is the hypothetical form of mature peer production under civic dominance, whose seeds are already emerging through the interstices of the dominant system.

The P2P infrastructures: Two axes and four quadrants

The P2P infrastructures, such as the Internet, are those infrastructures for communication, cooperation and common value creation that allow for permission-less interlinking of human cooperators and their technological aids. We argue that such infrastructures are becoming the general conditions of work, life and society (see only Bauwens, 2005). Of course, one should be aware of the danger of “Internet-centrism” (Morozov, 2014) and the perception that the Internet is the solution to every problem humanity is facing. However, change is unlikely to happen without sufficient ICT penetration since, as it has become evident, both the good and the evil aspects of human nature can be amplified and telescoped by the Internet (Mackinnon, 2013). P2P relational dynamics, which sometimes seem to epitomize the old slogan “Jeder nach seinen Fähigkeiten, jedem nach seinen Bedürfnissen!” (from each according to his ability, to each according to his need), are based on the distribution of the productive forces. First, the means of information, immaterial production, that is the networked computers, and now the means of physical manufacturing, that is machines that produce physical objects, are being distributed and interconnected. Just as networked computers democratized the means of production of information and communication, the emergent elements of networked micro-factories or what some (see Kostakis, Fountouklis and Drechsler, 2013; Anderson, 2012; Rifkin, 2014) call desktop manufacturing, such as 3D printing and computer-numerical-control (CNC) machines, are democratizing the means of making.

Of course, this is not an unproblematic process. In a time of extreme polarization and not having reached an equilibrium regarding the global governance of the Internet (Mueller, 2010), we have been witnessing conflicts for the control and ownership of distributed infrastructures. For example, the Internet, the world’s largest ungoverned space (Cohen and Schmidt, 2013), has become a highly contested political space (MacKinnon, 2013). On the one side, peer production signals for some fundamental changes to take place juxtaposing them against an old order that should be cast off (Bauwens, 2005; Benkler, 2006). On the other, the proposed legislations of ACTA/SOPA/PIPA that enforce strict copyright; the attempts for surveillance, public opinion manipulation, censorship and the marginalization of opposite voices by both authoritarian and liberal countries (MacKinnon, 2013); and “the growing tendency to link the Internet’s security problems to the very properties that made it innovative and revolutionary in the first place” (Mueller, 2010: 160), are only some of the reasons that have made some scholars (see Zittrain, 2008; Mackinnon, 2013) worry that digital systems may be pushed back to the model of locked-down devices centrally controlled information appliances. Hence, there appears to be a battle emerging amongst agents (several governments and corporations), which are trying to turn the Internet into a tightly controlled information medium, and users communities who are trying to keep the medium independent.

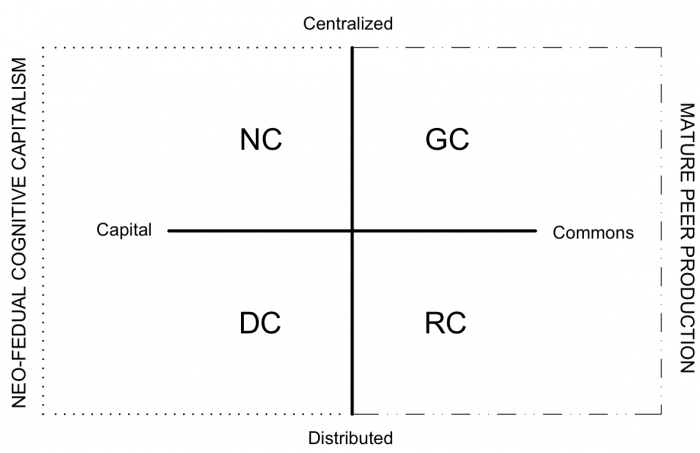

This book attempts to simplify possible outcomes by using two axes or polarities which give rise to four possible scenarios. Each quadrant stands for a certain scenario where each technological regime is dominant. This does not exclude the presence of the rest, however the dominant regime defines the kind of political economy which may prevail. The four scenario approach has been widely used as an exploratory tool that allows for fruitful discussions on policy-making (van der Heijden, 2005; Leigh, 2003) and sustainable strategic planning and development (Godet, 2000; Kelly et al., 2004). Each scenario has a descriptive role and outlines tentative political economies with the aim to spark imagination and serve as a route map for the future (Miles, 2004). Using scenarios is like rehearsing the future, according to Schwartz (1996). By rehearsing these future scenarios organizations, states and the civil society can adapt to what is happening and anticipate and influence what could transpire. In accordance with van der Heijden et al. (2002) and Schwartz (1996), our scenario framework consists of two dimensions which have high level of uncertainty and are crucial to future developments. The first axis presents the polarity of centralized versus distributed control of the productive infrastructure, whereas the second axis relates an orientation towards the accumulation of capital versus an orientation towards the accumulation or circulation of the Commons.

Within this context the following four future scenarios for economy and society are introduced: netarchical capitalism (NC), distributed capitalism (DC), resilient communities (RC) and global Commons (GC) (figure 5).

Netarchical and distributed capitalism differ in the control of the productive infrastructure but both are oriented towards capital accumulation and, thus, are parts of the wider value mode of cognitive capitalism. They actually form the mixed model of neo-feudal cognitive capitalism. On the other, the resilient communities and the global Commons reside in the, one might say auspicious, hypothetical model of mature peer production under civic dominance (right quadrants). The next parts shed light on each scenario in separate chapters, discussing also the co-existence of each pair of models which share a common orientation. Moreover, the third part attempts to introduce a few preliminary general principles for policy making and put forward some general policy recommendations with the goal to move from the left side of quadrants to the right one. Or to put it in the terms of the TEPS theory, to realize the full potential of an ICT-driven TEP while maximizing the benefits from technological progress for the largest part of the society.