Towards Integrated Local Sustainable Energy Solutions for Neighborhoods

* Report: Power to our neighbourhoods: towards integrated local sustainable energy solutions. Learning from success. A report by CAG Consultants for the. Ashden Awards for Sustainable Energy, June 2010

URL = http://www.ashdenawards.org/files/pdfs/reports/Full_Report_Power_to_our_neighbourhoods.pdf

Excerpts

From Chapter 3: Local sustainable energy initiatives

As outlined in chapter 2, local sustainable energy initiatives can play a crucial role in delivering a low carbon economy. They can delivery significant physical and technological change through energy saving measures and small-scale renewables. And they are also ideally placed to support individual and collective behaviour change.

What are they?

Local sustainable energy initiatives:

- Focused on a defined spatial area. Depending on the nature of the initiative, this area could be as large as a region (e.g. North-West England) or as small as a street. More usually, it is focused around a single town, village, neighbourhood or sub-region.

- Involve one, or a combination of, energy efficiency, renewable electricity or renewable heat.

- Are often local in that they are often unique to that area, being the result of local entrepreneurship and tailored to the needs of the area in question.

In this chapter, we pay particular attention to a wide range of such initiatives, focusing in particular on one type of local sustainable energy initiative, namely area-based energy efficiency schemes.

Case study examples

Throughout this report there are extensive references to case study examples of local sustainable energy initiatives and to their experiences and successes. Some of these initiatives are at different stages. Some have a track record of proven success, such as the Ashden Award winners. Others are less developed or recognised, but provide interesting insights nonetheless.

Table 3 summarises the main case study examples that we refer to throughout this report alongside key references from which information has been drawn. They are grouped by broad types of initiative, although many overlap and so are not exclusively limited to that category.

The shift towards area-based energy efficiency approaches

"Area-based" energy efficiency approaches are an increasingly common and lauded type of local sustainable energy initiative.

The Energy Saving Trust (EST) (2009) defines an area-based approach as one that “delivers energy efficiency measures in a spatial area. This could be a street, neighbourhood, a local authority area or a group of local authority areas”. Kirklees Warm Zone, and other Warm Zones, Hadyard Hill, Fintry, Community Energy Plus Home Health and Cumbria Energy Efficiency Advice Centre are all delivering variations of this type of approach.

Such approaches are now championed by many (for example Boardman 2007, CAG and Energy Action Scotland 2008, EST 2009, LGA 2009) as an excellent means of rolling out energy improvements. The Energy Saving Trust (EST, 2009, p2) say that “they are one of the most proactive and cost-effective methods for achieving significant CO 2 reductions ... [and] have been proven to be much more effective than costly blanket approaches known as „pepper-potting‟ that use little marketing intelligence to inform their delivery.”

This view of the way forward for reducing household emissions is strongly backed by the government advisory body - the Committee on Climate Change - that monitors the UK‟s progress on carbon emission reduction targets. A key recommendation of its 2009 assessment on progress was that the UK Government needed to:

“Make a major shift in the strategy on residential home energy efficiency, moving away from the existing supplier obligation, and leading a transformation of our residential building stock through a whole house and street by street approach, with advice, encouragement, financing and funding available for households to incentivise major energy efficiency improvements (Committee on Climate Change 2009)”.

Key elements of an area-based approach

Ashden Award winners have been at the forefront of developing this type of approach (e.g. Kirklees Warm Zone as a large-scale urban example and the Hadyard Hill project in rural South Ayrshire on a much smaller scale).

Area-based approaches typically include most, if not all, of the following elements:

- The local authority working in partnership with the local community, energy suppliers, installers and other local organisations. At Hadyard Hill the project was led by the Energy Agency on behalf of the local authority.

- Area-based delivery to gain economies of scale.

- Combining funding from several different sources such as the local authority‟s housing budget, CERT and other funding from energy suppliers.

- Intensive marketing campaign often using door-to-door leafleting and backed up by dissemination and support through trusted community networks.

- Trained assessors making door-to-door visits to check the current energy efficiency of dwellings and to identify appropriate measures for each household.

- A main focus on basic insulation measures such as cavity wall, loft insulation and draught proofing, sometimes accompanied by more advanced measures (e.g. the Hadyard Hill project also included solar thermal systems).

- Some projects have offered measures at no cost to the householder and without means testing (e.g. Hadyard Hill and Kirklees Warm Zone) but this has not necessarily been a feature of other area-based schemes.

- Many area-based schemes offer support to low-income households to ensure they are receiving their full social security and benefit entitlements.

Example: Kirklees Warm Zone

The Kirklees Warm Zone is probably the most well-known - and successful - example of an area-based energy efficiency approach.

Kirklees Council has worked in partnership with Scottish Power (CERT funding), Yorkshire Energy Services (Warm Zone manager) and Miller Pattison (installer) to create the Kirklees Warm Zone, a large-scale area-based approach to install basic home insulation measures (cavity wall and loft insulation). The Warm Zone includes the towns of Huddersfield and Dewsbury, and several other towns and villages in this part of West Yorkshire. The borough has a population of 401,000 people living in 171,000 households (157,000 occupied homes – i.e. excluding empty properties).

Both Kirklees Council and Scottish Power contributed £10 million to finance the Warm Zone with the largest part of the local authority‟s contribution being derived from the sale of its share in the local airport. All households in the district have been visited by trained independent assessors under contract to Yorkshire Energy Services. Where additional insulation is required they arrange for a contractor to install mineral-fibre insulation in lofts and cavity walls at no cost to the homeowner.

By March 2010 (three years from the start), the Warm Zone has benefited the community in a number of ways:

- 35,500 tonnes CO2 equivalent savings each year.

- 25% of the local population had benefited from energy efficiency measures with some 38,000 lofts insulated and 18,000 cavity walls filled.

- The creation of 129 local jobs as installers with Miller Pattison and as assessors and administrative staff at Yorkshire Energy Services.

- A significant reduction in fuel poverty.

- £8 million of fuel bill savings per year.

- Increased awareness and uptake of state benefit support by eligible residents.

- The distribution of carbon monoxide detectors and 25,800 referrals for fire safety checks.

Example: Rural South West Scotland

A recent analysis carried out for WWF Scotland (Cambium Advocacy 2009) assessed the impact of three area-based schemes modelled on Ashden Award winner the Hadyard Hill project. The non-means tested schemes in Hadyard Hill, Fintry and Girvan were compared with what had been achieved by the Scottish Government‟s Warm Deal programme which is not area-based, but provides a similar range of measures on a means tested basis. The three area-based schemes showed a generally better level of performance than Warm Deal.

The average cost to achieve £1/year savings on fuel bills by those receiving energy efficiency measures across the three projects was £1.85 compared to £2.45 for Warm Deal. Annual energy usage of treated houses in the three area-based schemes fell by between 18% and 24%.

The average cost to save one tonne of carbon dioxide per year across the three projects was £328 compared with £356 for Warm Deal. On average the households in the three area-based schemes saved between 1.3 and 3.1 tonnes of carbon dioxide per annum, averaging a 19% reduction in emissions.

In addition acceptance rates by households having surveys and reports ranged from 72% to 90% in the three area-based schemes. The Energy Agency reported that in other non- area-based programmes the response rate achieved was usually around 10%. This high response rate and the concentration of leads is a key factor in the lower delivery costs of the area-based schemes.

Take-up and coverage

A key challenge for many national programmes to cut carbon emissions is to achieve „good levels of take-up‟. This means that a significant number of energy users, whether domestic or commercial, are responding to initial contacts and also then implementing measures.

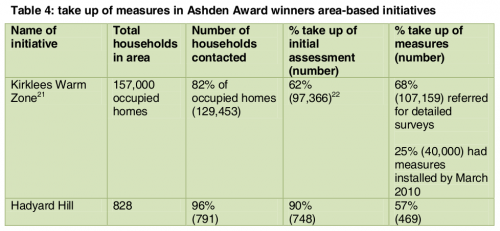

The experience of two Ashden Award winners shows that very high take-up rates and wide coverage is based on the trust resulting from community endorsement and involvement, good customer care (discussed later) and the availability of universally-free measures. Their performance is shown in table 4.

Comparing the performance of area-based schemes, both with other area-based schemes and with non-area based schemes is problematic for a number of reasons. Success can vary depending on the context in which they work in (e.g. some contain very high numbers of hard-to-treat homes), the approaches to marketing they adopt, the scope of the projects (some go beyond physical measures and into „softer‟ or behavioural measures that are more difficult to measure), the stage of delivery they are at, and inconsistency in the way data is collected and reported.

Nonetheless, the figures from Kirklees and Hadyard Hill suggest that these area-based approaches have achieved a high take up. Indeed, the success of these and other schemes has led the Committee on Climate Change to assert that a move towards more area-based schemes would deliver more carbon savings than CERT, the UK Government‟s current key scheme for improving household energy efficiency.

On the basis of analysis (Element Energy 2009, p159), the Committee concluded that take- up of measures under the main existing scheme (CERT) would be insufficient to deliver on national targets as it would deliver less than half of the emissions reduction potential. On the basis of the poor take-up being achieved under CERT, the Committee on Climate Change has made strong recommendations for an immediate and significant change of direction to an area-based approach.

The Committee on Climate Change also pointed to the disappointing results for installations of solid wall insulation measures. Government had projected that CERT might result in 150,000 solid wall insulation installations in the period 2008-2011. CERT actually delivered only 8,600 installations in its first year - just 5.7% of the Government‟s projection. There is as yet insufficient information to say whether area-based schemes can deliver a better take-up rate than CERT. The current CESP programme could provide this evidence.

Costs and cost-effectiveness

A review of other energy efficiency schemes revealed that there is currently little in the way of meaningful, comparable data on the costs of schemes.

However, the two schemes highlighted here suggest that good value for money can be achieved from area-based approaches. The cost of the schemes has been around £20million. With around 40,000 measures installed to date, the cost per measure has been approximately £500. The total cost of three Energy Agency schemes, covering 4167 properties, was £771,000 (Cambium Advocacy, 2009). With 1,584 measures installed, this gives an average cost per measure of £487.

High take-up rates are a significant factor in reducing costs. These cost reductions are the result of the much improved productivity of installers where there is a small distance between jobs. In the Kirklees Warm Zone the next job may well be the next house. Kirklees Warm Zone has found that the delivery of measures is showing productivity levels 50% higher than those experienced on comparable national programmes.

Costs can also be reduced through the economies of scale that area-based schemes can achieve. EST (2009) say that area-based approaches are up to 30% lower than their individual cost as a result of bulk purchase of insulation. However, achieving economies of scale is easier in urban areas than in rural areas where transport and storage costs, for instance, can make a significant difference.

Making comparisons between the costs of schemes is not straightforward. There is no consistent reporting framework for such approaches and so there are variations in the way data is collected, the way costs are calculated (e.g. whether they include the CERT subsidies or not) and because of the differences in the nature of the schemes and the types of measures that are installed.

Wider benefits

Area-based approaches can also deliver a number of wider benefits. These include:

- Local economic benefits. Involving local installers can create jobs and improve skills in the local area. EST (2009) say that research in the South East of England has shown that an average local authority running a three year area-based programme to insulate 46,000 lofts and cavities in their area could create 90 jobs. The Kirklees Warm Zone initiative has created 129 full-time equivalent jobs. Itestimates that every £1 invested in the scheme returns £4 into the local economy (Travers and Arup, 2009). In Hadyard Hill 2 local surveyors were trained and employed for the project, along with a project manager (Cambium Advocacy, 2009).

- Increased disposable income. The Kirklees Warm Zone expects to deliver annual fuel bill savings of around £200 to around 50,000 households when the scheme is completed (Audit Commission, 2009). In the Energy Agency Ayrshire schemes, annual disposable income in the community increased by £162,000 in Fintry, £561,000 in Girvan and £176,000 in Hadyard Hill. In both cases, the increases in disposable income can be expected to lead to indirect economic benefits, as local residents can spend on other things, including local goods and services (Ashden Awards, 2009)

- Benefit checks. The Warm Zone schemes have incorporated benefit checks, securing an additional £18 million in income for low-income households

- Improved health. Area-based schemes can lead to improved housing conditions and reductions in fuel poverty, which in turn can lead to improved health, reduced hospital admissions and can enable vulnerable people to live independently at home (Audit Commission, 2009).

Utilising an area-based approach in urban and rural areas

There is a common concern that urban areas are more likely to be favoured for area-based schemes, partly because of the economies of scale that can be achieved, and also because poverty indicators, such as the Index of Multiple Deprivation which is used to determine where CESP schemes can happen, score higher in urban areas. Schemes such as the Kirklees Warm Zone have amply shown the success of the approach in urban areas.23 Meanwhile, early indications from the CESP suggest that this will focus predominantly on urban areas - the first ten schemes, announced in October 2009 by British Gas, all focus on urban areas.

On the other hand, there have been some questions asked about the applicability of the area-based approach to rural areas. There is a particular concern that rural areas tend to have a high proportion of fuel poor, with many properties off the gas grid and paying for increasingly expensive oil and Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). However, our research has demonstrated that area-based schemes can also work successfully in rural areas. Detailed below is an example of the successful development of area-based schemes in the dispersed communities of South West Scotland.

Key lessons

- Area-based approaches can deliver significant levels of take up and coverage, especially when they are universally free.

- Significant economies of scale can be achieved through area-based approaches. This can make area-based approaches a cost-effective way of rolling out energy efficiency improvement

Other approaches to delivering local sustainable energy

Our research has also highlighted a range of other local sustainable energy initiatives that are helping to move neighbourhoods towards a low carbon future. These offer real benefits both in terms of carbon savings and wider sustainability gains. These could significantly enhance area-based approaches, through adding in additional elements including community engagement, behaviour change, renewable energy, supporting businesses, and long-term visioning and planning. These are explored below .

Priming and supporting community action

Participants at the practitioner workshops highlighted that local sustainable energy initiatives can benefit from strong community involvement. Indeed, the work of many Ashden Award winners already demonstrates this.

Community involvement can come in a variety of forms. In some instances, „strong communities‟ take the lead and develop their own initiatives (as will be discussed later on in the report). In other instances, local sustainable energy initiatives can work with communities to both „prime‟ them to take action, improving the likelihood of them taking up behavioural and physical measures, and to mobilise them to achieve wider progress towards a low carbon future.

The boxes below highlight two examples of how working with communities has increased understanding, improved behaviours and laid the ground for physical measures and real cuts in carbon emissions.

Priming community action

The Greening Campaign is a structured programme with three phases which supports communities taking their first steps towards sustainability, reducing their impact on climate change and planning for adapting to future climate change.

The programme is designed to excite communities, make it fun and to move towards being self-sustaining. The first phase involves households making small (largely behavioural) changes, such as switching the lights off when they leave the room, turning off inactive appliances and turning the thermostat down by one degree.

From these modest successes, they move onto bigger actions in the second phase. These involve the community acting together, for example local food initiatives and insulation and water saving programmes. They make full use of peer pressure as a motivator for action. The third phase - a community climate change adaptation toolkit - will be launched in July 2010.

In the community of Wallingford, Oxfordshire, 757 of the 3193 households took part in the first phase of the Greening Campaign and saved an estimated 384 tonnes of CO2 per year through behavioural measures alone. By December 2009 the campaign had saved 2,155 tonnes of CO2 in total and is now working in over 180 communities. This approach is involving an average of 13% of the population in recipient communities actively involved. The highest involvement achieved for phase one is 24%. The percentage typically increases when the community begins phase two.

The Campaign is now working with installers to move onto large-scale retrofit programmes. These are based on initiatives where participants have already educated themselves about the issues and are motivated by having already achieved some cuts in emissions.

Example: Mobilising communities in the Midlands

Ashden Award winner Marches Energy Agency (MEA) is another organisation that has worked with communities on an area-basis. It has worked with communities in the West and East Midlands through its Low Carbon Communities (LCC) Programme to encourage them to take action to reduce their energy use and carbon emissions, providing them with support and training to achieve these goals. By March 2010 LCC had run with 15 communities in total, with several more about to join the programme, saving over 2,000 tonnes of CO2 annually and directly benefitting more than 2,500 people.

The LCC programme works closely with the other strands of MEA‟s work. For example, work might begin in a community with an energy-themed pub quiz or film night run by MEA‟s communication and education programme, Carbon Forum. LCC will then follow this up, working with the community to reduce their emissions. This includes practical advice on behavioural measures as well as advice on how to get technical measures installed. LCC tends to be delivered where there is already a local group in existence - such as a Transition Initiative - as this provides an „in‟ to the community. LCC will typically work with a community for 24 months, with the aim that at the end of that period the community will have gained sufficient enthusiasm, knowledge, skills and confidence to continue taking further action to reduce emissions.

Supporting local energy supply and generation

Many successful local sustainable energy initiatives involve the development of a localised - and sometimes community-owned - energy supply.

Ashden Award winner ALIEnergy, which operates on the west coast of Scotland, helped communities to develop a sustainable energy supply as a precursor to their area-based energy efficiency schemes.

The most advanced example is possibly the Island of Gigha. With the expert help of ALIEnergy the islanders installed three wind turbines with a capacity of 670 kW which provide the community with 75% of their electricity requirements and an annual net income of around £75,000 from electricity sales. The revenues from the electricity sales from this small wind farm pay off the loan for the capital costs, but also provide a substantial contribution to the Gigha Community Trust. The Trust then funds energy efficiency improvements in the island‟s homes (the financial model for this project is discussed later).

This is just one example of how a deeper level of action to cut carbon emissions has been encouraged by community ownership of energy supply. This could be a significant additional feature to the area-based approach described in the previous section.

An alternative approach to energy supply is demonstrated by another Ashden Award winner, Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council (MBC). Barnsley MBC was heavily dependent on 133 outdated and polluting coal-fired boilers for heating 66 of its premises, including 26 district heating schemes. By 2004 many of these boilers were due for replacement. It took the decision to progressively replace these boilers with wood-chip fired biomass boilers as a way of cutting carbon emissions. Two of the early replacements involved the completion of a 470 kW wood-fuelled district heating scheme for 166 flats, and a 500kW scheme for the council depot. Wood chip boilers have also been installed in new buildings, instead of gas, such as the installation of a 500kW boiler at Barnsley MBC‟s civic headquarters. The wood-chip is processed from wood residues and coppice wood from woodlands and parks in the area around Barnsley. A new, local wood supply business has been created as a result of this development.

Similar initiatives to that in Barnsley are being developed by other Ashden Award winners in other parts of the UK, such as Bioregional‟s project to develop wood fuel supply chains, including a tree station in Croydon (Ashden Awards 2006).

Including energy supply in an area-based approach allows for the more comprehensive range of measures necessary for deep cuts in carbon emissions. An important aspect of this is the development of local heat distribution networks that will increase the viability of small-scale renewable energy generation. It also offers important collateral benefits for the local economy. For example by connecting fuel supply chains to locally sourced wood fuel, it creates local jobs and strengthens the local economy.

Developing local supply chains, creating local jobs

Local sustainable energy initiatives can also bring together key partners to develop supply chains for renewable energy fuel supply and installation, and expand the number and capacity of local installation companies. Detailed below is a successful example of how to provide this type of support and how it can provide commercial opportunities and benefits for the local economy.

Example: Devon

In 2006 Devon County Council and other partners set up Ashden Award Winner Renewable Energy for Devon (RE4D) to create and safeguard jobs and cut CO2 emissions.

In the first phase, it gave advice to 486 individuals and organisations, providing over five days of mentor support to each of 99 businesses and social enterprises. Advice was also given to schools, public sector organisations, communities and households. In total:

- £250,000 was given in capital grants.

- 109 renewable energy systems were installed.

- 37 local renewable energy installers were supported, with 20 receiving over five days support

- 55 new jobs were created in the renewable energy sector and combined turnover rose from £7m to £11m.

- £4.2m Energy savings totalled £4.2m for SMEs.

- 10 technology growth plans were produced. As of June 2009, 694 tonnes of CO2 are saved per annum, equivalent to the emissions of 282 homes, and the renewable energy sector in Devon has grown quicker than other equivalent areas. As of January 2010, over 90 renewable energy jobs have been created.

Partnership working lies at the heart of the successful operation of RE4D. The partners include the main funder, Devon County Council, but also a number delivery partners.

RE4D is tied into the community in Devon through these partners such as the Devon Association for Renewable Energy (DARE). DARE is a delivery partner and is a grassroots not-for-profit membership organisation, managed by elected directors. DARE was formed by five people who were brought together as representatives of their communities for a European funded project. DARE is completely independent and receives no core funding, being funded by membership subscriptions and consultancy work, but some services are still provided voluntarily by its directors. DARE provides mentoring support for community clients, as well as technical support for other client „mentors‟.

Supporting energy intelligent businesses

If area-based initiatives are to move beyond the domestic sector they the need to involve local businesses and to provide appropriate support to enable them to cut their own carbon emissions as part of improving their economic efficiency.

The experience of one Ashden Award winner, ENWORKS, shows that a regionally based partnership can deliver support to businesses at the local level, while ensuring strategic alignment with regional and national policies and programmes of work.

Example: Enworks Regional partnership

ENWORKS is a regional partnership operating since 2001 in the North West of England that includes the RDA, Environment Agency, North West Chambers of Commerce, plus a number of national groups. It provides support to business of all sizes, from all sectors and in all locations on energy and resource efficiency (including materials and water) and on environmental business risk (e.g. compliance with environmental regulations and adapting to climate change). At the end of 2009 ENWORKS received approval for £9.9 million of investment to extend its existing service and continue to offer specialist support to the region‟s businesses until 2013. This funding is from the Northwest Regional Development Agency (£6.4 million) and the European Regional Development Fund (£3.5 million).

ENWORKS is currently providing support to over 1,000 companies each year, support that delivers 66,000+ tonnes of CO2 savings per year with a further 248,000+ tonnes of annual savings in the pipeline. The companies are achieving cost savings through resource efficiency of £23 million per year with a further £77 million in the pipeline. Recent analysis of these results shows that 58% of cost savings have been achieved with no capital investment from the businesses, evidence that simple changes in practice can deliver significant economic and environmental benefits.

At a local level the support is delivered through a network of partners including not-for- profit organisations (e.g. Groundwork Trusts and Cumbria Rural Enterprise Agency) and sector-support organisations (e.g. Chemicals Northwest and Food Northwest). This ensures that wherever a business is based there is always a support-provider nearby that understands and can respond to local need and is locally accountable. The regional structure of the partnership ensures that all businesses receive a consistent and quality- assured service and that all delivery partners benefit from shared learning across the network, both avoiding duplication of effort and enabling best practice to be identified and disseminated. In addition, rather than duplicate services that are provided by others, such as The Carbon Trust, ENWORKS encourages businesses to access these services where appropriate.

ENWORKS collects data on the efficiency improvements made by the businesses it supports using the ENWORKS Efficiency Toolkit, a bespoke piece of online software that businesses can access to prioritise, track and report the economic and environmental savings from their improvement actions. The data held in the Toolkit has been made available to a range of stakeholders including local authorities (e.g. in relation to National Indicator 186) and central government departments (e.g. BIS & DECC) who need to monitor the impact of actions on carbon emission reduction (ENWORKS 2009 and Nicholson 2010).

ENWORKS is delivering support that is successfully coupling cost savings for companies with substantial cuts in carbon emissions. This model of delivery through local partners could link in with an area-based approach.

Ashden Award winner the MEA has also made supporting SMEs a key element of its work through its Low Carbon Enterprise programme. The programme offers impartial technical support and project delivery capability to public, private and third sector organisations across the West and East Midlands, advising on the efficient use of energy, the reduction of carbon emissions and the installation of renewable energy.

One of the Low Carbon Enterprise projects, Low Carbon Communities for Business, worked with over 100 small businesses across four communities in Shropshire .Each received technical assistance with the implementation of sustainable energy measures in their premises. This led to 25 sustainable energy projects and six business diversification projects with a total of £210,000 of grant funding. The estimated savings from the project are at least 200 tonnes of CO2 with £50,000 in energy cost savings per annum for the businesses.

Example: „Hackbridge Sustainable Suburb‟ long term vision

A project that is yet to deliver outcomes, but is developing a novel planning-led approach to delivering local sustainable energy. A Master Plan (Tibbalds 2009) sets out a long-term vision incorporating new development alongside refurbishment of existing buildings. Its success is that it has already brought together the local authority planners and the community to develop a truly comprehensive plan to transform a whole area.

Example: Bioregional Development Group, A planning led area-based approach

Ashden Award Winner, Bioregional Development Group describes itself as “an entrepreneurial charity which initiates and delivers practical solutions that help us to live within a fair share of the earth‟s resources - what we call one planet living” (see www.bioregional.com). It is best known for its groundbreaking Beddington Zero Energy Development (BedZed) in the London Borough of Sutton.

As part of the wider One Planet Sutton initiative, Sutton Council has been working with, Bioregional to transform the district of Hackbridge in the London Borough of Sutton into a sustainable suburb.

In planning terms it will elevate the existing local centre to a district centre (Hackbridge already includes BedZed). The proposals combine community involvement work with a large- scale retrofit programme for existing homes, and the development of 1100 new environmentally-friendly homes. The initiative covers energy use, waste and recycling, sustainable transport, low impact materials, food, water, habitats, local identity, economic regeneration and improving community wellbeing (Tibbalds 2009 and www.oneplanetsutton.org/hackbridge).

One of the early features of the initiative has been its success in bringing together a range of partners, including the local authority, an entrepreneurial charity (Bioregional), community groups and residents, and a major retailer, B&Q.

This initiative is still at the planning and consultation stage, but through its integrated and long-term approach, it demonstrates a different way of delivering neighbourhood solutions to sustainable energy."