Peer to Peer Finance Mechanisms to Support Renewable Energy Growth

This page represents the summary of the work done from May 2009 to May 2011 by Joshua Pearce's research group.

Peer-to-Peer Financing Mechanisms to Accelerate Renewable Energy Deployment

Abstract: Despite the clear need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, lack of access to capital and appropriate financing mechanisms has limited the deployment of renewable energy technologies (RETs). Feed-in tariff (FIT) programmes have been used successfully in many countries to make RETs more economically feasible. Unfortunately, the large capital costs of RETs can result both in the slow uptake of FIT programmes and incomplete capture of deployment potential. Subsidies are concentrated in financial institutions rather than the greater population as traditional bank loans are required to fund RET projects. This article critically analyses and considers the political, financial and logistical risks of an innovative peer-to-peer (P2P) financing mechanism. This mechanism has the goal of increasing RET deployment capacity under an FIT programme in an effort to equitably distribute both the environmental and economic advantages throughout the entire population. Using the Ontario FIT programme as a case study, this article illustrates how the guaranteed income stream from a solar photovoltaic system can be modelled as an investment and how P2P lending mechanisms can then be used to provide capital for the initial costs. The requirements for and limitations of these types of funding mechanisms for RETs are quantified and discussed and future work to deploy this methodology is described.

Keywords: feed-in tariff; funding innovation; microfinance; peer to peer lending; photovoltaics; renewable energy; sustainability

Source: K. Branker, E. Shackles & J. M. Pearce (2011): Peer-to-peer financing mechanisms to accelerate renewable energy deployment, Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1:2, 138-155. open access

Whilst the first paper above covers using the P2P Lending mechanisms under only FIT jurisdications for RETs (Option A), the second paper suggests how this concept can be expanded to off-grid projects (Options B).

Kadra Branker and Joshua M. Pearce, “Accelerating the Growth of Solar Photovoltaic Deployment with Peer to Peer Financing” Solar 2011: 40th American Solar Energy Society National Solar Conference Proceedings, pp. 713-720 (2011).

Background and Major Findings

FITs

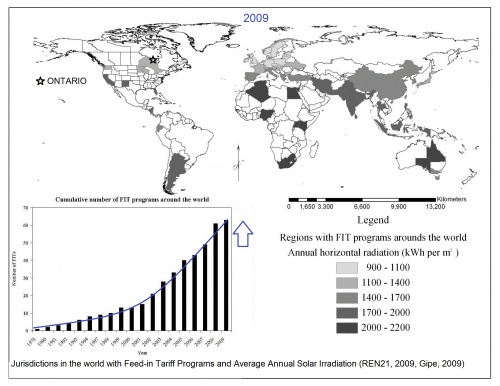

FITs (Feed-in Tariffs) represent the most common incentive for RETs. Particularly, solar PV and wind have seen explosive growth in jurisdictions with FITs. Fig 1 shows the potential market for FITs, with more than 60 jurisdictions having them, such that a global P2P lending netwrk could be beneficial. Fig. 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of countries, provinces and states with enacted FITs. The inset shows the cumulative number of jurisdictions that have enacted FITs from 1978 to early 2009. The average annual solar irradiation adapted from the Atmospheric Science Data Center is illustrated for the FIT jurisdictions.

P2P Lending

It is easy to consider P2P lending (peer to peer lending) platforms as an alternative method for funding RET projects given that traditional financial institutions have rigid collateral and minimum loan size requirements.

P2P Lending platforms employ loans that are either secured (with collateral considerations) or unsecured (using other attributes of the borrower). Also, depending on the platform, there can be pooled and/or direct lending. Furthermore, there are 4 distinct business models with examples summarized in Table 1, with variations and mixtures of these models existing. (i) microfinance (MF) (non-profit), (ii) social investing (SI) (low return), (iii) marketplace and/or auction (MP/A) (profit maximization-high return) and (iv) social lending service (SLS) (low return between family and friends)

Table 1: Summary of Examples of P2P Lending Platforms (*NB.Many other specific organizations exist)

| Organization | Business Model | Details | Interest | Direct /Pooled |

Fees | Loan Term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kiva (2005) | MF | enables lenders to invest in micro- entrepreneurs in the developing world through an MFI | None | Both | No | 6-12 months |

| Energy in Common, EIC (2010) | MF/charity | Uses MFIs to collect data and interact with clients, but focuses on raising funds directly for energy related investments of the poor, primarily in Ghana, but expanding to Nigeria and Tanzania | None | Direct | No | < 2 to >12 months |

| United Prosperity (2008) | MF/loan guarantor | Involves a loan guarantee from the “lender” at no interest to an MFI to raise more funds for micro-entrepreneurs | None | Pooled | No | variable |

| Wokai (2006) | MF/charity | Donations to Chinese entrepreneurs as a tax deduction in the United States | None | Pooled | No | N/A |

| Microplace (2006) | MF/SI (low return) | Investment in MFI funds in several locations, including Mexico, India and the United States, for the poor or small entrepreneurs | 1% to 6% | Pooled | No | < 1 to >3 years |

| MYC4(2007) | SI/MF/A | Connects lenders anywhere with African entrepreneurs at low interest rates | Variable rate dependent on risk | Both | Yes | 6 - 24 months |

| Prosper (2006) | MP/A | lenders can bid interest rates and other loan terms as a competitive market | Market rate dependent on risk | Both | Yes | 3 years |

| Lending Club(2007) | MP | investment at rates dictated by the loans market | Market rate dependent on risk | Both | Yes | 3 years |

| CommunityLend (2006) | MP/A | lenders can bid interest rates and other loan terms as a competitive market | Market rate dependent on risk | Both | Yes | 3 years |

| Virgin Money (2001) | MP/A | facilitator for loans between family and friends only that does the paperwork and processes the transactions (recently changed model to facilitate loans between strangers)[1] | Fixed negotiation between family and friends | Both | Yes | Fixed negotiation between family and friends |

Proposed P2P Lending Framework

Given the actual economics of RETs, it is clear from Table 1, that modifications need to be made to existing P2P networks in order to maximize the benefits of RETs.The main requirements are:

- Larger and longer term loans (in line with true costs and payback for a system)

- Methods to invoke Online Trust and reduce Risk of Default (employ social networks, guarantors and recommendations)

- Loan security (By ensuring the system has insurance and third party verification and only using products with best available warranties)

- Ensuring that tax deductions or carbon offsets will be recognized by lenders’ countries

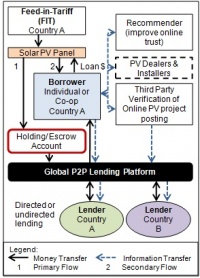

Fig 2. summarizes the proposed global lending networks.

Option A: P2P Lending for FIT supported RET

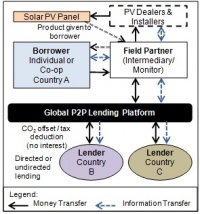

Option B: P2P Lending for off-grid RET

Fig. 2: Model Framework

| Option A | Option B |

|---|---|

|

|

| P2P-FIT-RET Network with PV example | P2P-off grid-PV Network example |

Examples and Implications

In the papers, a solar PV system is used to show how the models might work from a financial aspect.

Option A - P2P-FIT-RET Network

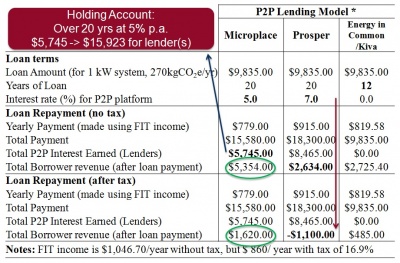

The analysis used a 1 kW Solar PV system in Ontario, Canada under the FIT that provides 80.2 ¢/kWh for a period of 20 years for systems <10 kW. Using RetScreen4 and inputs for Kingston, Ontario, the 1 kW system would generate 1,380 kWh per year (ignoring degradation)which is a FIT income of $1,106.70 per year. With an estimated installed cost of the system is $9,835, a $60 annual insurance cost and an assumed 2% social discount rate, the IRR is 8.6%.Finally, the system would result in an annual GHG reduction of 270 kg of CO2 emissions/year. The analysis compared the effect of no tax versus a personal income tax of 16.9%.

In the case of Option A, the framework was applied to some existing platforms with the required modifications for loan term and size. Given the modifications, existing platforms would be capable of financing the Solar PV system, ensuring a return for both the borrower and the lender. The holding account, which is akin to having an RRSP in Canada, proved a possible incentive for the lender offering a lower interest rate to the borrower. However, depending on the combination of interest rate and tax rate, the borrower loses money which is an important policy consideration (Table 2).

Option B -P2P-off-grid RET Network

Missing Table 3: Image:OptionBeg.jpg|400px|right

In the case of Option B, a case study from Energy in Common is presented where the P2P lending network is used to provide the funding for the solar PV system.

If the simple example shown is extended to larger systems or pooled community lending for bigger businesses, the potential carbon offsets could become substantial. If these carbon offsets are coupled to existing and growing carbon markets, they represent a significant supplementary source of income for the project.

One concern of the existence of two options is Option A may dominate the investments in solar PV under FITs,depriving the impoverished off-grid communities from the same investment. Although it should be noted that the returns for the off-grid communities are potentially much higher than those from on-grid FITs.

Related Research Pages

Related Papers

- K. Branker, E. Shackles, J.M. Pearce, “Peer-to-peer financing mechanisms to accelerate renewable energy deployment ”, Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1 (2), April 2011 , pp. 138-155.[2]

- Kadra Branker and Joshua M. Pearce, “Accelerating the Growth of Solar Photovoltaic Deployment with Peer to Peer Financing” Solar 2011: 40th American Solar Energy Society National Solar Conference Proceedings, pp. 713-720 (2011).

Corporate Examples

- Convergence Energy offers investors a stake in a large PV project by investing at least $160,000 for a system, which amounts to ~80 panels erected across three tracking towers. Each system of three towers generates up to 20 kWs.[3]

Tags

MOST, Photovoltaics, Energy policy, Finance, Microfinance, P2P finance