PART THREE: THE HYPOTHETICAL MODEL OF MATURE PEER PRODUCTION: TOWARDS A COMMONS-ORIENTED ECONOMY AND SOCIETY

This entry is about "Network Society and Future Scenarios for a Collaborative Economy" co-authored by Vasilis Kostakis and Michel Bauwens. The scholarly book is published by Palgrave Macmillan and here you may find a draft of it.

Want to read the ebook (mobi/epub)?

You may contact the authors at kostakis.b AT gmail.com and/or michelsub2004 AT gmail.com

<=Previous part || Next part=>

Plenty of attention has been gathering around the Commons (see only Ostrom, 1990; Hardt and Negri, 2011; Barnes, 2006; Benkler, 2006; Bollier and Helfrich, 2012). But what is its concept all about? As we will discuss below, echoing Bollier (2014), the Commons might simultaneously refer to shared resources, a discourse, a new/old property framework, social processes, an ethic, a set of policies or, in other words, to a paradigm of a pragmatic new societal vision beyond the dominant capitalist system. To begin with, in general it is a term that refers to shared resources where each stakeholder has an equal interest (Ostrom, 1990). The Commons sphere can include natural gifts such as air, water, the oceans and wildlife, and shared 'assets' or creative work like the Internet, the airwaves, the languages, our cultural heritage and public knowledge which have been accumulating since time immemorial (Bollier, 2002, 2005, 2009). The Commons, with a capital 'C' to highlight its (re)emergence as a powerful counterweight to government and corporate power, also includes goods that have been developed and maintained jointly by a community (Siefkes, 2012; Mackinnon, 2012). These goods are shared according to certain community-defined rules (Siefkes, 2012). Take for example the Wikipedia encyclopedia or FLOSS, with regard to certain community-driven governance mechanisms through which these projects have managed to remain sustainable, functional and productive. Therefore, it could be said that every Commons scheme basically has four interlinked components: a resource (material and/or immaterial; replenishable and/or depletable); the community which shares it (the users, administrators, producers and/or providers); the use value created through the social reproduction or preservation of these common goods; and the rules and the participatory property regimes that govern people's access to it. There is an interplay among the aforementioned components and, therefore, as we discuss below, Commons should mostly be viewed as social processes.

In contrast to the traditional understanding of property, a key characteristic of the Commons is that no one has exclusive control over the use and disposition of any particular resource (Benkler, 2006). Unlike most things in modern capitalist society, the Commons is neither private nor public, in the traditional sense (The Ecologist, 1994, p. 109). The Commons may signify the absence of state, corporate and/or individual control, in favor of distributed control based upon non-exclusionary, P2P property regimes (Boyle, 2003a, 2003b; Bauwens, 2005). It would be interesting, here, to address the relation between the definitions of the public domain and the Commons. Both concepts are often used interchangeably, yet the latter seems to overtake the former in terms of popularity (Boyle, 2003a, 2003b). The public domain concept is related to the 'outside' of the IP system, it entails items free of property rights, and, thus, emphasizes totally open accessibility: nobody is excluded and everything is allowed (Boyle, 2003b). On the other side, the Commons can be restrictive in a sense. For instance, some Commons-based projects give the freedom to use and/or modify the resource under the condition that new contributions will also be open to others under the same conditions. Hence, the Commons is not an ungoverned space but rather a legal regime for ensuring that the artifacts of community-based productive efforts remain under the control of that community. 'The GPL, the CC licenses, databases of traditional knowledge, and sui generis national statutes for protecting biological diversity all represent innovative legal strategies for protecting the commons' (Bollier, 2009, p. 219). Therefore, we may consider the public domain as a container in which the Commons represents its content of jointly held resources (Ciffolilli, 2004). When Hardin was discussing the tragedy of the Commons in his 1968 essay, he was actually describing a regime free of property rights and/or of governance mechanisms, where everybody could take and use anything with no constraint. However, in the Commons, a distinct community of users governs the resource (Bollier, 2014, p. 3). Hardin's thesis has also been called 'The Tragedy of Unmanaged, Laissez-Faire, Common-Pool Resources with Easy-Access for Non-Communicating, Self-Interest Individuals' (Hyde, 2010, p. 44). We do not argue that humans are not self-interested and competitive beings, but that they simultaneously exhibit deep concern for fairness, communication, reciprocity, solidarity and social connection: 'all these human traits', Bollier writes (2014, p. 3), 'lie at the heart of the commons'. Benkler (2011) brings empirical evidence to the fore and describes how cooperation in Commons-based projects triumphs over self-interest, making a case against the blind adherence to 'free market' dogmas.

On the one hand, the neoliberal economics have integrated both the state and the market into one organism/entity, the 'market/state', which stresses the 'deep interdependencies among large corporations, political leaders, and government bodies' (Bollier, 2014, p. 1). The market/state rarely takes into consideration any 'positive' human trait when designing and implementing public policies. Rather, it sees competition, individualism and private property as key drivers of growth and innovation. A critique against neoliberalism could be that it systematizes only a very limited aspect of complex human nature. In contrast, the P2P-driven, Commons-oriented social systems are designed not for one motivation (rational self-interest), but for a multitude of motivations (it is motivation-agnostic). No matter how 'selfish' the motivation of the Linux or Wikipedia contributors, the system is designed to ensure that participating individuals contribute to the Commons. In the narrow sense, it could be said that the P2P-driven, Commons-based production efforts encapsulate complex human behavior so that it can contribute to the creation of Commons.

Moreover, the mainstream economic theory and many of its prominent indexes (such the Global National Product, GDP) are incapable of recognizing the value produced through various Commons-based projects. Typically, the Commons-oriented forms of production do not produce commodities, but rather use value, and, thus, the latter is not treated as property (The Ecologist, 1994). Hence, the Commons is not recognized as having economic value and cannot take part in market exchange within its social/collective/non-exclusive format (Brown, 2010). To tackle this problem, the capitalist political economy would treat the shared resource as a commodity. Enclosed by a certain exclusive property regime –property is a political institution, as Brown (2010) points out – the resource can now enter the market and become a means for profit maximization. According to this perspective, wealth is synonymous with the accumulation of properties; therefore, everything has to be commodified, even things that are more than commodities:

Labor is only another name for a human activity which goes with life itself, which in its turn is not produced for sale but for entirely different reasons, nor can that activity be detached from the rest of life, be stored or mobilized; land is only another name for nature, which is not produced by man; actual money, finally, is merely a token of purchasing power which, as a rule, is not produced at all, but comes into being through the mechanism of banking or state finance. None of them is produced for sale. The commodity description of labor, land, and money is entirely fictitious. (Polanyi, 1944/2001, p. 75-76)

From the parliamentary enclosures in England (15th-19th Century) to the recent “corporate enclosures”, a vast range of commonly-held resources has been enclosed, privatized, traded in the market, and thus abused (Bollier, 2002; McCann, 2012). The first wave of enclosure forced people who had been making their living outside the wage-mechanism to leave their lands for the cities, where they began to be dependent on wages for their survival (Brown, 2010). They became workers, cogs of the capitalist mode of production. If we follow Marx (1992/1885, 1993/1973), this was an alienation of the self from itself, because what workers produced was totally divorced from who they were, thus damaging their essential integrity. And as Brown (2010, p. 120) remarks: 'the alienation of labor caused by an economics of property has repeated itself with a vengeance in our relationship with the living planet'.

However, in the second wave of enclosure, taking place nowadays, there is a robust counter-power: the distributed movement of the Commons with a local and global orientation. There are areas where the market is retreating, not to the bureaucracies and command structures, but instead to the Commons (Stadler, 2014): from seed-sharing cooperatives, the FLOSS and open hardware communities, to localities that use alternative currencies, resilient communities and movements such as community-supported agriculture and Transition Towns. We are observing a re-emergence and flowering of new economic forms based on equity, including the cooperative economy, the social economy, and the solidarity economy. The reduction of transaction and coordination costs through the modern ICT and the distribution of productive capital in the form of networked personal computers have strengthened this current and given birth to new forms of production based on the collaborative efforts of autonomous individuals. These collaborative modes of social production, which principally celebrate open access to knowledge, have mainly been labeled 'Commons-based peer production' (see Benkler, 2006, 2011; Bauwens, 2005, 2009). The first Commons-based peer production (CBPP) projects were observed in the sphere of information economy, where the marginal cost of information production is very low, if not nearly zero (Benkler, 2006; Bauwens, 2005; Rifkin, 2014; Kostakis, 2012). A plethora of projects, such as the development of the Linux Kernel, the Apache Web server, the office suite Libre Office, the browser Mozilla Firefox, and the operating system Ubuntu, and free/open content projects such as the encyclopedia Wikipedia, exemplify the productive and governance processes of CBPP. Moreover, we have observed similar patterns of production in some emerging and even not-so-new Commons-based, P2P projects in the primary and secondary economic sector.

As a first example, the Centre for Sustainable Agriculture in India is a community-managed agriculture model that focuses on developing and promoting locally adapted and sustainable farming systems. It was developed to provide a viable alternative for Indian farmers who were being crushed by the cost of chemical pesticides, fertilizers and genetically modified seeds. Open source seed sharing networks and community seed banks have been set up to overcome the various IP limitations that turned seeds, traditionally considered a Commons, into objects of exclusionary property (Dafermos, 2014). These efforts aim to create a knowledge database (an agricultural Commons, one might say) for the conservation and revival of existing varieties as well as for practices of participatory plant breeding on a local basis (Aoki, 2009; Kloppenburg, 2010; Raidu and Ramanjaneyulu, 2008). Moreover, several producer-consumer cooperatives have been set up with their own meeting grounds (Dafermos, 2014). Another P2P project that goes beyond the information sphere of production is the Transition Towns movement, a grassroots network of communities that are working to build resilience in response to peak oil, climate destruction, and economic instability. Its approach is based on 'a concisely crafted methodology for catalyzing community participation via a messy open source organizational process' (Robb, 2009). Likewise, the Open Source Ecology project concerns the development of several low-cost machines meant to cover all sorts of agricultural, and even manufacturing, needs. The design information for these machines is available under Commons-oriented licenses adapted for hardware. Another initiative of great interest is the RepRap project, which initially included the development of a low-cost open source 3D printer that could replicate itself by printing a number of its own components. Its lack of IP restrictions has enabled a huge community to experiment with and improve on the design. As a result, several models based on the first RepRap model have recently been developed. In addition, multiple start-ups but also some large companies began making low-cost 3D printers based on the RepRap design. Another example of CBPP efforts in the manufacturing sector would be the Wikispeed project. Its aim is to produce an energy efficient and modular car made at a fraction of the price of a conventional car. Developed by an international community of volunteers, the Wikispeed car can be built on demand in micro-factories with the use of free/open source software and hardware. Anyone can use or contribute to the project, as all of the specifications are available.

Under the lenses of a processual vision of social change (Papadopoulos, Stephenson and Tsianos, 2008), these socially driven projects could be considered as escape routes to alternative forms of social organization. If the political agenda for a world driven by social-oriented values should include the removal of property relations as the economy's foundation and their replacement with civic relation, or, access to resources over ownership (Brown, 2010), then the Commons-oriented movement seems to be emblematic of the aforementioned approach. IP rights are reconfigured to prevent the monetization and expropriation of knowledge. New institutionalized licenses have been introduced to allow the unobstructed sharing of information, including the Creative Commons licenses, the General Public Licenses (GPL) or the Peer Production Licenses (PPL). These forms of property allow the social reproduction of Commons-oriented projects. In other words, knowledge is considered a common good and becomes available to anyone through the utilization of the Internet. Thus, experimentation, collaborative innovation and development are truly promoted while remaining community-driven (Moglen, 2004; Wenden de Joode, 2005; Benkler, 2006).

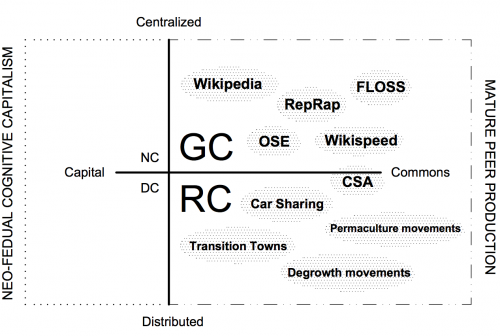

However, the aforementioned projects, which form what we could call 'the hypothetical model of mature peer production under civic dominance' (right quadrants), may differ in their focus on the Commons as either local or global. We use the term 'local' as a space distinct from the larger regional, national and international spaces (Sharzer, 2012). In addition, local can be also relational; seen as a moment in the global capital accumulation (Sharzer, 2012). On the other side, the use of the term 'global' recognizes the possibility that a project might be local, but with the meaning of a spatial territory. This is to say, a project can be rooted somewhere, but the produced use value is principally aimed at a global audience. Our main idea is that networks are global-local, thus, for-benefit orientations can either focus on pure re-localization strategies (though they can be globally organized to achieve this), or they can take a global perspective and create global commons through global for-benefit associations and global entrepreneurial coalitions. In the 'resilient communities' (RC) scenario (bottom-right) there is distributed control over the P2P infrastructures, that is, both the back-end and the front-end are solely distributed. The focus here is mostly on re-localization and the re-creation of local communities. It is often based on an expectation of a future marked by severe shortages or, in any case, increased scarcity of energy and resources, and so takes the form of lifeboat strategies. Initiatives like the Transition Towns movement, the degrowth movement or certain aspects of the India-based CSA can be seen in that context. The 'Global Commons' (GC) approach (upper-right) is in contrast to the aforementioned focus on the local, focusing instead on the global Commons. Advocates and builders of this scenario argue that the Commons should be created and fought for on a transnational global scale. The necessity to scale up the Commons is evident in this particular scenario. As becomes obvious, contrary to the left quadrants we do not deal here in terms of technological regimes. Instead, we are more interested in the orientation that communities and individuals have when utilizing P2P infrastructures. The following chapters discuss separately and in more detail each scenario, concluding with some transition proposals for moving towards a global Commons-oriented economy, which arguably can take full advantage of the current TEP's potential in a more sustainable and just way.

Resilient communities

The primarily ecological and subsequently economic, social, cultural and political crisis the world is facing is the point of departure for the resilient communities approach. This scenario contains strategies and policies for strengthening the ability to adapt to such uneven changes. It makes the case for a transition to a low-carbon, sustainable sharing economy based on social justice and co-operative interactions between people, where economic growth is out of the picture (Lewis and Conaty, 2012). For instance, the degrowth movement along with the Transition Towns, the car sharing and the general permaculture movements can be seen in this context (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1. The Commons-oriented quadrants

The theoretical bedrock of the degrowth movement is the so-called “degrowth economics”, associated with the work of Latouche (2009). According to this body of thought, a radical shift has to take place from growth as the main objective of the modern economy toward its opposite, that is, contraction and downshifting (Foster, 2011; Latouche, 2009). Latouche's work has since given rise to new intellectual movements and inspired a revival of radical Green thought, especially in Europe, as manifested by some prominent conferences in Paris (2008) and Barcelona (2010) (Foster, 2011). The Transition Towns movement, among others, has been influenced by the ideas of degrowth economics. The goal here is the radical relocalization of politics, economics and culture to autonomous and self-sufficient communities, in order to become resilient to mega-changes, such as peak oil and climate change. Hopkins — who, in 2006, created a working model of a Transition Town community in Totnes, UK — first introduced this concept in his 2008 book The Transition Handbook. Since then there have been over a hundred networked transition communities in existence or in the planning stages (see Chamberlin, 2009; Hopkins, 2011). Such communities are of a size that would allow members to have a strong personal influence over collective decisions (Hopkins, 2008, 2011). The Transition Towns concept has as its bedrock not only open source organizational practices, but also the principles of permaculture in combination with resilience and relocalization. Permaculture, a term which stands for 'permanent agriculture', is the design and maintenance of agricultural ecosystems which have the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems (Mollison, 1988). As Mollison (1988, p. ix-x) puts it:

The philosophy behind permaculture is one of working with, rather than against nature; of protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless action; of looking at systems in all their functions rather than asking only one yield of them; and of allowing systems to demonstrate their own evolutions.

A system based on permaculture principles and practices can evolve, self-organize, and thereby survive almost any change: there is no insistence on a single culture, which would shut down learning and cut back resilience (Meadows, 2008, p. 160). Hence, in order to counter the volatility and fragility of the dominant system, building resilience locally is fundamental (Lewis and Conaty, 2012). It is vital to shift to a system with the capacity 'to evolve without losing its core sense of identity or purpose' (Wilding, 2011, p. 19). Therefore, resilience can be seen as the degree to which the system is capable of learning, self-organizing and adapting while remaining coherent (Carpenter et al., 2001; Walker et al., 2009; Folke, 2006). Walker and Salt (2006) along with Lewis and Conaty (2012) highlight some key aspects of any system's resilience: diversity, modularity (consisting of components which can independently operate and be modified), reciprocity, social capital (that is, trust and bonds among members) and tightness of feedback loops. In general:

[A] system’s resilience is enhanced by more diversity and more connections, because there are more channels to fall back on in times of trouble or change. Efficiency, on the other hand, increases through streamlining, which usually means reducing diversity and connectivity... Because both are indispensable for long-term sustainability and health, the healthiest flow systems are those that maintain an optimal balance between these two opposing pulls” (Walker and Salt, 2006: 121).

Steps and policies towards the world that the resilient communities' scenario envisions can be: the support of a dynamic local economy; the empowerment of local governance and local control; the optimization of assets; the valuing of local distinctiveness and of permaculture; the development of sustainable infrastructures (for example, affordable housing; interest-free banks; community land trusts; autonomous energy production, and so on); and the construction of a social solidarity economy (Wilding, 2011; Lewis and Conaty, 2012).

The local focus of the resilient communities quadrant becomes, however, evident. In extreme forms, this scenario contains simple lifeboat strategies and initiatives, aimed at the survival of small communities in the context of generalized chaos. They may build on the idea that we must accept the reality of considerably more expensive energy and food (Lewis and Conaty, 2012). What marks such extreme initiatives is arguably the abandonment of the ambition of scale while the feudalization of territorial integrity is considered mostly inevitable. Though global cooperation and web presence may exist, the focus remains on the local. Most often, political and social mobilization at scale is seen as not realistic, and doomed to failure. In the context of our profit-making versus Commons axis though, these projects are squarely aimed at generating community value. We consider them a healthy reaction against global problems and environmental degradation. Resilient communities try to be immune to the dominant system and they use P2P practices and technologies for good reasons. They try to support individuals' physical and psychological well-being by generating a positive sense of place, localizing the economy within ecological limits, and securing entrepreneurial/community stewardship of the local Commons (Wilding, 2011). They do not, however, build global structures. According to our understanding, the issue is how to organize a global counter-power able to propose alternative modes of social organization on a global scale. For Sharzer (2012), 'localism' is the fetishization of scale, as some positive benefit is ascribed to a place precisely because it is small. He (2012) argues that resilient communities and other similar projects inevitably become parts of the broader capitalist economy, because they do not confront capitalism, but rather avoid it. Initiatives like Transition Towns are growing movements, though with local focus. They can co-exist in harmony within the next scenario of global Commons by the logic that whatever is heavy is local (for instance, desktop manufacturing technologies), and whatever is light is global (for instance, global knowledge Commons).

In addition to the focus on the local, the degrowth narrative is central to the resilient communities' scenario. We believe, quoting Foster (2011), 'that the ecological struggle, understood in these terms, must aim not merely for degrowth in the abstract but more concretely for de-accumulation – a transition away from a system geared to the accumulation of capital without end'. To realize such a transition it is crucial to develop pragmatic alternatives. Similar to how we began talking about 'alter-globalization' when the 'antiglobalization' movement became counter-intuitive, we now need to become more positive and start talking about 'alter-growth' scenarios instead of thinking in anti-growth/degrowth terms. Arguably, the issue is not to produce and consume less per se, but to develop new models of production which work on a higher level than capitalist models. We consider it difficult to challenge the dominant system if we lack a working plan to transcend it. A post-capitalist world is bound to entail more than a mere reversal to pre-industrial times. As the TEPS theory informs us, the adaptation of current institutions and the creation of new ones take place in the deployment phase of each TEP. We claim that the times are, finally, mature enough to introduce a radical political agenda with brand new institutions, fueled by the spirit of the Commons and aiming to provide a viable global alternative to the capitalist paradigm beyond degrowth or antiglobalization rhetorics.

Global Commons

Several global-oriented Commons-based projects such as FLOSS, Wikipedia, Wikispeed, RepRap, or Open Source Ecology (OSE) highlight the emergence of technological capabilities shaped by human factors, which in turn shape the environment under which humans live and work. They create what Benkler (2006, p. 31) calls new 'technological-economic feasibility spaces' for social practice. These feasibility spaces include different social and economic arrangements, where profit, power, and control do not seem as predominant as they have in the history of modern capitalism. From this new communicational, interconnected, virtual environment, a new social productive model is emerging, different from the industrial one. We are witnessing the emergence of a new proto-mode of production, that is, Commons-based peer production, based on distributed, collaborative forms of organization. It is developing within capitalism, rather as Marx (1979) argued that the early forms of merchant and factory capitalism developed within the feudal order. In other words, system change is back on the agenda, but in an unexpected form, not as a socialist alternative, but as a Commons-based alternative. As we saw, capitalism in its present form is facing limits, especially resource limits, and in spite of the rapid growth of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) economies, it is undergoing a process of decomposition. The question is whether the new proto-mode can generate the institutional capacity and alliances needed to break the political power of the old order. Ultimately, the potential of the new mode is the same as those of previous proto-modes of production – to emancipate itself from dependency on the old decaying mode, so as to become self-sustaining and thus replace the accumulation of capital with the circulation of the Commons. In an independent circulation of the Commons, the common use value would directly contribute to the further strengthening of the Commons and of the commoners' own sustainability, without dependence on capital. How could this be achieved? Before dealing with this tempting question, we believe that it is crucial to shed more light on the social, economic and political dynamics of CBPP.

When it comes to information, CBPP is more productive than market-based or the 'bureaucratic-state' systems (Benkler, 2006). It produces social well-being because it is based on people's intrinsic positive motivations (for instance, the need to create, learn, and communicate) and synergetic cooperation among participants and users (Benkler 2006; Hertel, Niedner, and Herrmann, 2003; Lakhani and Wolf, 2005). As Hertel, Niedner, and Herrmann (2003, p. 1174) mention in their study of the incentives of 141 Linux kernel community participants, the former were driven 'by similar motives as voluntary action within social movements such as the civil rights movement, the labor movement, or the peace movement'. Benkler (2006) makes two intriguing economic observations which challenge some 'eternal truths' of the mainstream economic theory. Commons-based projects fundamentally challenge the assumption that in economic production, the human being solely seeks profit maximization. Volunteers contribute to information production projects, while they gain knowledge, experience, and reputation, and communicate with each other motivated by intrinsically positive incentives. This does not mean that the monetary motive is totally absent; however, it is relegated to a peripheral concept (Benkler, 2006). The second challenge is directed against the conventional wisdom that, in Benkler's (2006, p. 463) words, 'we have only two basic free transactional forms – property-based markets and hierarchically organized firms'. CBPP can be considered a third way, and should not be treated as an exception but rather as a widespread phenomenon, although it is not currently counted in the economic census (Benkler, 2006). In terms of neoliberal economics, what is happening in CBPP can arguably be considered only in the sense that individuals are free to contribute, or take what they need, following their individual inclinations, with an invisible hand bringing it all together yet without any monetary mechanism. Hence, in contrast to markets, in CBPP the allocation of resources is not done through a market-pricing mechanism. Hybrid modes of governance are employed, and what is generated is not profit, but a Commons.

CBPP is based on practices that stand in contrast to those of the market-based business firm. More specifically, CBPP is opposed to industrial firms’ hierarchical control and authority. Instead, it is based on communal validation and negotiated coordination [see, for instance, Dafermos' (2012) study on the Free BSD project's collectivist and consensus-oriented governance system] as quality control is community-driven, and conflicts are solved through an ongoing mediated dialogue (for example, in Wikipedia, the dialogue takes place in the discussion page of each article). However, in cases such as the internal battle between inclusionists and deletionists, Wikipedia's lack of a clearly defined constitution led a small number of participants to create rules in conflict with others: persistent, well-organized minorities adroitly handled their opponents, seriously challenging the sustainability of the project (Kostakis, 2010). Therefore, it must be stressed that when abundance is replaced by scarcity (as happened in Wikipedia when deletionists demanded strict content control), power structures emerge because CBPP mechanisms cannot function well (Kostakis, 2010). Investigating prominent CBPP projects, O'Neil (2009) analyzed the tensions generated by the distribution of authority, and showed that it is important to openly discuss how power and authority actually work in CBPP in order to be able to organize differently. His proposal is that leaders must support maximum autonomy for participants toward a more egalitarian situation. Of course, a special characteristic of CBPP is that if these benevolent dictators (Kostakis, 2010) abuse their power, their leadership becomes malicious, and a substantial exodus of community members often occurs. These members, due to the low marginal costs of information, are free to start their own new project, using the already Commons-based peer produced information if they wish.

Further, CBPP is not driven by the for-profit orientation that defines market projects, as peer projects have a for-benefit orientation, creating use value for their communities. This does not mean that the profit motive is totally absent in CBPP projects, but rather that incentives such as learning, communication, and experience come to the fore. That is how the human person actually operates, rather than the imagined homo economicus. Besides, Hess' (2005, p. 515) 'private-sector symbiosis' hypothesis outlines that emphasis on technology and product innovation can lead 'to the articulation of social movements goals with those of inventors, entrepreneurs, and industrial reformers' (2005, p. 516). Therefore, 'a cooperative relationship emerges between advocacy organizations that support the alternative technologies/products, and private sector firms that develop and market alternative technologies' (Hess, 2005, p. 516). For instance, the case of Linux and IBM comes in accordance with Hess' argument for the private sector symbiosis and subsequent incorporation and transformation of the technologies which may, though, provoke, an object conflict. 'As the technological/product field undergoes diversification', Hess (2005, p. 515) writes, object conflicts 'erupt over a range of design possibilities, from those advocated by the more social movement-oriented organizations to those advocated by the established industries'. It can be claimed that an object conflict is taking place concerning the Makerbot Replication 2 3D printer, which is partly closed source. This may, arguably, lead to the loss of Makerbot's community (Giseburt, 2012).

Instead of the division of labor in CBPP, a distribution of modular tasks takes place, with anyone able to contribute to any module, while the threshold for participation is as low as possible (see only Benkler, 2006; Bauwens, 2005; Tapscott and Williams, 2006; Dafermos and Söderberg, 2009). Modularity is a key condition for CBPP to emerge: 'Described in technical terms, modularity is a form of task decomposition. It is used to separate the work of different groups of developers, creating, in effect, related yet separate sub-projects' (Dafermos and Söderberg, 2009, p. 61). Torvalds (1999), the instigator of the Linux project, maintains that the Linux kernel development model requires modularity, because in that way, people can work in parallel. Empirical research (see only MacCormack, Rusnak and Baldwinet, 2007; Dafermos, 2012) shows that modular design is characteristic not just of Linux but of the FLOSS development model in general. 'The Unix philosophy of providing lots of small specialized tools that can be combined in versatile ways', Carson (2010, p. 208) writes, 'is probably the oldest expression in software of this modular style'. We also observe the same approach in the development of one of the most prominent CBPP projects, namely Wikipedia. Articles (that is, modules), which consist of sections (or, sub-modules), are built upon other articles and entries produced, and thus can be used individually as well as in combination. By breaking up the raw elements into smaller modules, there is both an abundance of options in terms of remixing them, as well as a low participation threshold, since the individuals can have access to the modules rather than centralized forms of capital. Further, modularity leads to stigmergic collaboration. In its most generic formulation, according to Marsh and Onof (2007, p. 1), 'stigmergy is the phenomenon of indirect communication mediated by modifications of the environment'. Therefore, in the context of CBPP, stigmergic collaboration is the 'collective, distributed action in which social negotiation is stigmergically mediated by Internet-based technologies' (Elliott, 2006).

Moreover, CBPP is opposed to the rivalry (scarcity of goods) through which market profit is generated, as sharing the created goods does not diminish the value of the good, but actually enhances it (Benkler, 2006). To this, one might add that CBPP is facilitated by free, unconstrained, and creative cooperation of communities, which lowers the legal restrictive barriers to such an exchange and invents new, institutionalized ways of sharing. In terms of property, as we have discussed, the Commons is an idea different from both state property, where the state manages a certain resource on behalf of the people, and from private property, where a private entity excludes the common use of it. It is, however, important to highlight that the contributors of CBPP projects do have interests and rights concerning their work and are interested in protecting their intellectual property (O'Mahony, 2003). Thus, the Commons-oriented approach to property 'does not assert that sharing is an ethical absolute' (after all everyone is, or should be, free to choose what type of license they will adopt), but tries to balance the rights of innovators with the rights of the public (O'Mahony, 2003; von Hippel and von Krogh, 2003). It becomes obvious that what sets CBPP apart from the proprietary-based mode of production – the 'industrial one' (Benkler, 2006) – is its modes of governance (consensus-oriented governance mechanisms) and property (communal shareholding), whose foundation stones are the abundance of resources, openness, and the power of meaningful human cooperation. These are the very characteristics of CBPP which provide the capacity to deliver genuinely innovative, remarkable results (thus contesting allegations of low quality: see only Keen, 2007; Lanier, 2010) such as the Apache web server, Mozilla Firefox browser, Linux kernel, BIND (the most widely used DNS software), Sendmail (router of the majority of e-mail), and a myriad of emerging open source hardware projects.

Of course, beyond the great potential of CBPP, there may well be numerous obstacles, theoretical and practical problems, and negative side effects. However, taken in this idealized context, CBPP arguably carries some aspects which create a political economy where economic efficiency, profit, and competitiveness cease to be the sole guiding stars (Moore and Karatzogianni, 2009), while civil society attains a more important role, bringing (back) the notion of the Commons into the heart of the economy (Orsi, 2009). Under these lenses, the Commons can be seen as a legitimate vehicle of citizenship or as an equivalent of Tocqueville's (2010) civil society, through which citizens mobilize and express their interests while protecting their rights (Mackinnon, 2012). It can be central to the process of civilizing the economy, which would require a strong notion of citizenship – of membership in a global civil society (Brown, 2010). The Commons movement is removing property relations as our political economy's foundation and is replacing them with civic relations that define our bonds with each other – at work, in neighborhoods, in cities and in global communities (Brown, 2010). The Commons are long-term social and material processes that cannot be created overnight: 'in order to become meaningful they must exist over an extensive period of time' (Stadler, 2014, p. 31). In other words, the various spheres of the Commons are products of P2P creative processes as they expand horizontally and in dense interconnections with each other. Therefore, we must go beyond a material understanding of the concept and approach the Commons not only as a resource or as a property regime, but mainly as a social process. Producing a categorization or taxonomy of the Commons by a type of resource can be misleading, as Bollier (2014) warns us:

While choosing to categorize commons by the type of resource involved is tempting, a focus on the resource alone can be misleading. For example, a “knowledge commons” on the Internet is not simply about intangible resources such as software code or digital files; such a commons also requires physical resources to function (computers, electricity, food for human beings). By the same token, “natural resource commons” are not just about timber or fish or corn, because these resources, like all commons, can only be managed through social relationships and shared knowledge.

In other words, to quote Helfrich (2013), 'all commons are social, and all commons are knowledge commons'. Our relationships to shared goods that are managed as Commons should be the focal point and, thus, we should discuss the process of Commoning. In other words, we should discuss the process of the circulation of the free/open/participatory: 'free' and 'open' ensures access to raw material to build the Commons; 'participatory' refers to the process of broad participation in order to actually build it. The Commons, then, becomes the institutional format used to prevent private appropriation of shared creations, and the circle is closed when Commons-generated material is once again free/open raw material for the next circulation of the Commons.

Τhe 'Global Commons' approach (upper-right) focuses on a larger scale in relation to the resilient communities quadrant, that is, on the Commons with a global orientation (Figure 7.1). Advocates and builders of this scenario argue that the Commons should be created and fought for on a transnational global scale. Though production is distributed and therefore facilitated at the local level, the conjunction of CBPP with desktop manufacturing technologies could create sustainable business ecologies. There, the resulting micro-factories, essentially networked on a global scale, would profit from mutualized global cooperation, both on the design of the product and on the improvement of common machinery. 'Micro-factories' is a concept that refers to small dimension, automated factories capable of greatly conserving resources like space, energy, materials and time (Tanaka, 2001; Okazaki, Mishima, and Ashida, 2004). They are likely to feature automatic machine tools, assembly systems, evaluation and control systems, a quality inspection system and waste elimination system (Kussul et al., 2002; Koch, 2010). For example, see the Wikispeed's project micro-factory in Seattle, which is a licensed light-industrial space the size of a shipping container, used as a prototyping facility for cars that can get more than 100 miles per gallon (Denning, 2012). The Wikispeed car is produced voluntarily by a network of developers from all over the world, who have managed to significantly reduce the development time and cost compared with conventional car manufacturing, through the use of methods similar to those of CBPP (Dafermos, 2014; Denning, 2012). The Wikispeed project was launched in the 2008 Progressive Insurance Automotive X-Prize competition for the development of energy-efficient cars (Dafermos, 2014). The resolution to apply CBPP development methods to car manufacturing was what separated this project from its competition (Dafermos, 2014). When the founder of this project, Joe Justice, posted his plans on the Web, volunteers gathered and shortly after, a functioning prototype was presented (Denning, 2012; Halverson, 2011). More than 150 volunteers contribute now, and their goal is to deliver Wikispeed as a complete car for $17,995, and as a kit for $10,000 USD (Wikispeed, 2012). To sum up, as Dafermos (2014) puts it, the case of Wikispeed, just like that of Open Source Ecology and RepRap projects, demonstrates how a technology project can leverage the open design Commons and P2P infrastructures to engage the global community in its development. Most importantly, Wikispeed suggests a model of distributed manufacturing that is well-suited to a post-fossil fuel economy: a model which is small-scale ('on-demand'), decentralized, energy-efficient and locally controlled (Dafermos, 2014).

Any distributed enterprise, like the ones being developed around the aforementioned projects, is seen in the context of transnational 'phyles', that is, alliances of ethical enterprises that operate in solidarity around a particular knowledge Commons (P2P Foundation, 2014; de Ugarte, 2014). As the key terrain of conflict is around the relative autonomy of the Commons vis-a-vis for-profit companies, we are in favor of a preferential choice towards entrepreneurial formats which integrate the value system of the Commons, rather than profit-maximization. In that context, phyles, in other words the creation of businesses by the community, can make the Commons viable and sustainable over the long run. Advocates and builders of this scenario struggle for a shift from the current flock of community-oriented businesses towards business-enhanced communities. They believe that we need corporate entities which are sustainable from the inside out, not just via external regulation from the state, but from their own internal statutes and links to Commons-oriented value systems. We are arguably living the endgame of neoliberal material globalization based on cheap energy, which necessitates relocalization of production (see the resilient communities scenario). However, we have new possibilities for online, affinity-based socialization, coupled with the resulting physical interactions and community building. The value-creation communities of this quadrant might be locally based but are globally linked. Out of that, there may come new forms of business organization, which are substantially more community-oriented. This scenario sees no contradiction between global open design collaboration, and local production: both can occur simultaneously, so the relocalized reterritorialization will be accompanied by global tribes, organized in phyles. The various Commons, based on shared knowledge, code and design, will be part of these new global knowledge networks, but closely linked to relocalized implementations.

Therefore, political and social mobilization on the regional, national and transnational scale is seen as part of the struggle for the transformation of institutions. Participating enterprises are vehicles for the commoners to sustain global Commons as well as their own livelihoods. This scenario does not take social regression as a given, and believes in sustainable abundance for the whole of humanity. It envisions a transition to a paradigm which would include new decentralized and distributed systems of provisioning and democratic governance, escaping the pathologies of the current political economy and constructing an ecologically sustainable alternative (Bollier, 2014). To achieve such a transition, the global Commons scenario suggests that we should work on building both global and local political and social infrastructures. Next, we venture some general transition proposals for the state and the market in order to realize the full potential of the ICT-driven TEP in a more sustainable and just way.

Transition proposals towards a Commons-oriented economy and society

In the midst of the current techno-economic transformations, humanity is at a crossroads. How will a degraded natural environment sustain a political economy based on the assumption that natural resources are an endless sink? How will the modern, participatory ICT be fine-tuned, with the assumption that potentially abundant cultural/knowledge resources should exist in artificial scarcity? What value models will be adopted for a deployment period to come? Which model will prevail? 'When the changes happen faster than expectations and/or institutions can adjust, the transition can be cataclysmic', Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2011) write. To avoid such a cataclysm, we arguably need political and social mobilization on the regional, national and transnational scale, with a political agenda that would transform our expectations, our economy, our infrastructures and our institutions in the vein of a Commons-oriented political economy. The latter is not a utopia or simply a project for the future. Rather, it is rooted in an already existing social and economic practice, that of the CBPP, which is producing Commons of knowledge, code, and design, and has created real economies like the FLOSS economy, the open hardware economy and others. In its broadest interpretation, concerning all the economic activities emerging around open and shared knowledge, it has increasingly been contributing trillions of dollars to the GDP of the USA, according to the Fair Use Economy report (Rogers and Szamosszegi, 2011) (and one should reckon how difficult it is for the GDP index to consider socially produced use value).

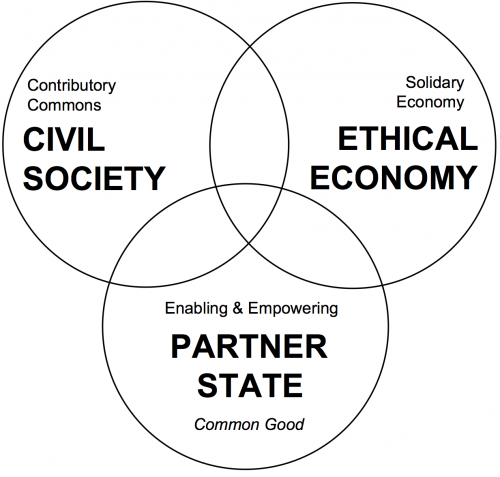

We have already described the micro-economic structures of this emerging Commons-oriented economic model, which we can summarize as follows: at the core of this new value model are contributory communities, consisting of both paid and unpaid labor, which are creating common pools of knowledge, code, and design. These contributions are enabled by collaborative infrastructures of production, and a supportive legal and institutional infrastructure, which enables and empowers the collaborative practices. These infrastructures of cooperation, that is technical, organizational, and legal infrastructures, are very often enabled by democratically-run foundations. These foundations are more generically called 'for-benefit associations', which may create code/design/knowledge depositories; protect against infringements of open and sharing licenses; organize fundraising drives for infrastructure; and organize knowledge sharing through local, national and international conferences. Thus, they are an enabling and protective mechanism. Finally, successful projects create an economy around the Commons pools, based on the creation of added value products and services that are based on the common pools, but also add to them. This is done by entrepreneurs and businesses that operate in the marketplace. Most often, these are for-profit enterprises, creating an 'entrepreneurial coalition' around the Commons and the community of contributors. They hire developers and designers as workers, create livelihoods for them, and also support the technical and organizational infrastructure, also including the funding of foundations. On the basis of this generic micro-economic experiences, it is possible to deduce adapted macro-economic structures as well, which would include a civil society that consists mainly of communities of contributors creating shareable Commons; of a new state form, which would enable and empower social production generally and create and protect the necessary civic infrastructures; and an entrepreneurial coalition which would conduct commerce and create livelihoods (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1. The Commons-oriented economic model of mature peer production

If we look at the micro-level, we recommend the intermediation of cooperative accumulation. In today's FLOSS economy we have a paradox: the more 'communist' the sharing license we use (that is, no restrictions on sharing) in the peer production of free software or open hardware, the more capitalist the practice (that is, multinationals can use it for free). Take for example the Linux Commons which has become a corporate Commons as well, enriching big, for-profit corporations. It is obvious that this works in a certain way and seems acceptable to most free software developers. But is this way optimal? Indeed, the GPL and its variants allow anyone to use and modify the software code (or design), as long as the changes are integrated back in the common pool under the same conditions for further users. Our argument does not focus on the legal, contractual basis of the GPL and similar licenses, but on the social logic that they enable, which is: it allows anybody to contribute, and it allows anybody to use. In fact, this relational dynamic is technically a form of 'communism': from each according to his/her abilities, to each according to his/her needs. This paradoxically allows multinational corporations to use free software code for profit maximization and capital accumulation. The result is that we do have an accumulation and circulation of information Commons, based on open input, participatory processes, and Commons-oriented output; but it is subsumed to capital accumulation. Therefore, it is not currently possible, or at least easy, to have social reproduction (that is, to create sustainable livelihoods) within the sphere of the Commons. The majority of the contributors participate on a voluntary basis, and those who have an income make a living either through wage-labor or alliances with capital-driven entities. Hence the free software and culture movements, however important they might be as new social forces and expression of new social demands, are also, in essence, 'liberal' in the tradition of the political ideology of liberalism. We could say they are liberal-communist and communist-liberal movements, which create a 'communism of capital'.

The question is whether Commons-based peer production, that is, a new proto-mode of production, can generate the institutional capacity and alliances needed to break the political power of the old order. Ultimately, the potential of the new mode is the same as those of the previous proto-modes of production – to emancipate itself from its dependency on the old decaying mode, so as to become self-sustaining and thus replace the accumulation of capital with the circulation of the Commons. This would be an independent circulation of the Commons, where the common use-value would directly contribute to the further strengthening of the Commons and of the commoners' own sustainability, without dependence on capital. How could this be achieved? Is there an alternative? We believe that there is: to replace the non-reciprocal licenses, that is those which do not demand a direct reciprocity from its users, with one based on reciprocity. We argue that the Peer Production License (PPL), designed and proposed by Kleiner (2010), exemplifies this line of argument. PPL should not to be confused with the Creative Commons (CC) non commercial (NC) license, as its logic is different. The CC-NC offers protection to individuals reluctant to share, as they do not wish a commercialization of their work that would not reward them for their labor. Thus the CC-NC license stops further economic development based on this open and shared knowledge, and keeps it entirely in the not-for-profit sphere. The logic of the PPL is to allow commercialization, but on the basis of a demand for reciprocity. It is designed to enable and empower a counter-hegemonic reciprocal economy that combines a Commons that is open to all that contribute, while charging a license fee for the for-profit companies who would like to use it without contributing. Not that much changes in practice for the multinationals; they can still use the code if they contribute, as IBM does with Linux. However, those who do not contribute should pay a license fee – a practice they are used to. Its practical effect would be to somehow direct a stream of income from capital to the Commons, but its main effect would be ideological, or if you like, value-driven.

The entrepreneurial coalitions that are linked around a PPL-based Commons would be explicitly oriented towards their contributions to the Commons, and the alternative value system that it represents. From the point of view of the peer producers or commoners, a Commons-based reciprocal license, like PPL, would allow the contributory communities to create their own co-operative entities. In this new ecology, profit would be subsumed to the social goal of sustaining the Commons and the commoners. Even the participating for-profit companies would consciously contribute under a new logic. This proposal would link the Commons to an entrepreneurial coalition of ethical market entities (co-ops and other models) and keep the surplus value entirely within the sphere of commoners/co-operators, instead of leaking out to the multinationals. In other words, through this convergence (or rather combination) of a Commons model for abundant immaterial resources, and a reciprocity-based model for the 'scarce' material resources, the issue of livelihoods and social reproduction could be solved. The surplus value would be kept inside the Commons sphere itself. It is the co-operatives that would, through their co-operative accumulation, fund the production of immaterial Commons, because they would pay and reward the peer producers associated with them. In this way, peer production could move from a proto-mode of production, unable to perpetuate itself on its own outside capitalism, to an autonomous and real mode of production. It would create a counter-economy that could be the basis for reconstituting a 'counter-hegemony' with a for-benefit circulation of value. This process, allied to 'pro-Commons' social movements, could be the basis for the political and social transformation of the political economy. Hence we might move from a situation in which the communism of capital is dominant, to a situation in which we have a 'capital for the Commons', increasingly insuring the self-reproduction of the peer production mode.

The new open co-operativism would be substantially different from the previous form. In the old one, internal economic democracy is accompanied by participation in market dynamics on behalf of the members, using capitalist competition. There is an unwillingness to share profits and benefits with outsiders, therefore, no creation of the Commons. We argue that an independent Commons-oriented economy would need a different model in which the co-operatives produce Commons and are statutorily oriented towards the creation of the common good. To realize their goals they should adopt multi-stakeholder forms of governance which would include workers, users-consumers, investors and the concerned communities. Today we have a situation where open communities of peer producers are largely oriented towards the start-up model and are subsumed to profit maximization, while the co-operatives remain closed, use exclusive intellectual property licenses, and, thus, do not create a Commons. In the new model of open co-operativism, a merger should occur between the open peer production of the Commons and the co-operative production of value. The new open co-operativism would: i) integrate externalities; ii) practice economic democracy; iii) produce Commons for the common good; iv) and socialize its knowledge. The circulation of the Commons would be combined with the process of co-operative accumulation, on behalf of the Commons and its contributors. In the beginning, the immaterial Commons field, following the logic of free contributions and universal use for everyone who needs it, would co-exist with a co-operative model for physical production, based on reciprocity. But as the co-operative model would become more and more hyper-productive through its ability to create sustainable abundance in material goods, the two logics could merge.

It is important to highlight that the Commons-based reciprocal licenses, like PPL, are not merely about redistribution of value, but about changing the mode of production. Our approach is to transform really existing peer production, which today is not a full mode of production, being incapable of assuring its own self-reproduction. This is exactly why the convergence of peer production in the sphere of abundance must be linked to the sphere of co-operative production, to ensure its self-reproduction. As with past phase transitions, the existence of a proto-counter-economy and the resources that this allocates to the counter-hegemonic forces are absolutely essential for political and social change. This was arguably the weakness of classic socialism, in that it had no alternative mode of production and could only institute state control after a takeover of power. In other words, it is difficult, if not impossible, to wait and see the organic and emergent development of peer production into a fully alternative system. If we follow such an approach, peer production would just remain a parasitic modality dependent on self-reproduction through capital. We argue that the expectation that one can change society merely by producing open code and design, while remaining subservient to capital, is a dangerous pipe dream. Through the ethical economy surrounding the Commons, by contrast, it becomes possible to create non-commodified production and exchange. We thus envision a resource-based economy which would utilize stigmergic mutual coordination through the gradual application of open book accounting and open supply chain. We believe that there will be no qualitative phase transition merely through emergence, but that it will require the reconstitution of powerful political and social movements which aim to become a democratic polis. And that democratic polis could indeed, through democratic decisions, accelerate the transition. It could take measures that obligate private economic forces to include externalities, thereby ending infinite capital accumulation.

However, such changes at the level of the micro-economy might not survive a hostile capitalist market and state without necessary changes at the macro-economic level (Kostakis and Stavroulakis, 2013). We should not ignore the fact that the state has its own interests in perpetuating its bureaucracy and legitimacy. Gajewska (2014) emphasizes this argument through the case of the campus food services (free lunches) at Concordia University as an example of peer production in the physical world. She describes the tension between the university administration and the P2P food services collectives which were producing food Commons. The project started with 'direct action' occupying university space for cooking, eventually recognized by Concordia University. What we realize is that a transition narrative should take into account the possibility for creating spaces of democratic accountability from below. For example, in the aforementioned case, the university was the framework through which students could pool resources in the form of fee levies and organize for-benefit projects (Gajewska, 2014). Hence, there is a need for transition proposals carried by a resurgent social movement that embraces new value creation through the Commons, and becomes the popular and political expression of the emerging social class of peer producers and commoners. This movement should arguably be allied with the forces representing both waged and cooperative labor, independent Commons-friendly entrepreneurs, and agricultural and service workers.

To begin with, we introduce the concept of the Partner State Approach (PSA), in which the state becomes a 'partner state' and enables autonomous social production. The PSA could be considered a cluster of policies and ideas whose fundamental mission is to empower direct social-value creation, and to focus on the protection of the Commons sphere as well as on the promotion of sustainable models of entrepreneurship and participatory politics. It is important to emphasize that we consider the 'partner state' as the ideal condition for a government to pursue (as is the case in Ecuador with the FLOK society project) and the P2P movement to fight for. While people continue to enrich and expand the Commons, building an alternative political economy within the capitalist one, by adopting a PSA the state becomes an arbiter, retreating from the binary state/privatization dilemma to the triarchical choice of an optimal mix amongst government regulation, private-market freedom and autonomous civil-society projects. Thus, the role of the state evolves from the post-World War II welfare-state model, which could arguably be considered a historical compromise between social movements for human emancipation and capitalist interests, to the partner state one, which embraces win-win sustainable models for both civil society and market. In such an approach, the state would strive to maximize openness and transparency while it would systematize participation, deliberation, and real-time consultation with the citizens. Thus, the social logic would move from ownership-centric to citizen-centric. The state should de-bureaucratize through the commonification of public services and public-Commons partnerships. Public service jobs could be considered a common pool resource, and participation could be extended to the whole population. Furthermore, representative democracy would be extended through participatory mechanisms (participatory legislation, participatory budgeting, and so on). It would also be extended through online and offline deliberation mechanisms as well as through liquid voting (real-time democratic consultations and procedures, coupled with proxy voting mechanisms). In addition to this, taxation of productive labor, entrepreneurship and ethical investing, as well as taxation of the production of social and environmental goods should be minimized. On the other hand, taxation of speculative unproductive investments, taxation on unproductive rental income and taxation of negative social and environmental externalities should be augmented. In these ways, the partner state would sustain civic Commons-oriented infrastructures and ethical Commons-oriented market players, reforming the traditional corporate sector in order to minimize social and environmental externalities. Last but not least, of great importance would be the engagement of the partner state in debt-free public monetary creation while supporting a structure of specialized complementary currencies.

The second component of a Commons-oriented economy would be an ethical market economy, that is, the creation of a Commons-oriented social/ethical/civic/solidarity economy. Ethical market players would coalesce around the Commons of productive knowledge, eventually using peer production and Commons-oriented licenses to support the social-economic sector. They should integrate common good concerns and user-driven as well as worker-driven multistakeholders in their governance models. Ethical market players would move from extractive to generative forms of ownership, while open, Commons-oriented ethical company formats are privileged. They should create a territorial and sectoral network of 'chamber of Commons' associations to define their common needs and goals and interface with civil society, commoners, and the partner state. With the help from the partner state, ethical market players would create support structures for open commercialization, which would maintain and sustain the Commons. Ethical market players should interconnect with global productive Commons communities (that is, open design communities) and with global productive associations (phyles) which project ethical market power on a global scale. We suggest that ethical market players should adopt a 1 to 8 wage differential and minimum and maximum wage levels. The mainstream commercial sector should be reformed to minimize negative social and environmental externalities, while incentives which aim for a convergence between the corporate and solidarity economy must be provided. Hybrid economic forms, like fair trade and social entrepreneurship, could be encouraged to obtain such convergence. Distributed micro-factories for (g)localized manufacturing on demand should be created and supported in order to satisfy local needs for basic goods and machinery. Institutes for the support of productive knowledge should also be created on a territorial and sectoral basis. Education should be aligned with the co-creation of productive knowledge in support of the social economy and the open Commons of productive knowledge. Therefore, all publicly funded research and innovation should be released under the GPL [for an extensive discussion of this proposal, see Boldrin and Levine's (2013) as well as Pearce (2012)]. Additionally, Commons infrastructures for both immaterial and material goods have to be created: in such a political economy, society is seen as a series of interlocking Commons supported by an ethical market economy and a partner state that protects the common good and creates supportive civic infrastructures. Local and sectoral Commons would create civil alliances of the Commons to interface with the chamber of the Commons and the partner state. Interlocking for-benefit associations (knowledge Commons foundations) would enable and protect the various Commons. In addition to this, solidarity cooperatives should form public-Commons partnerships in alliance with the partner state, while the ethical economy sector could be represented by the chamber of Commons. Also, the natural commons should be managed by a public-Commons partnership and based on civic membership in Commons trusts.

We would like to stress that this list of transitional strategies and preliminary proposals for policy making is general and non-inclusive. By no means does this chapter intend to formulate a specific economic plan or a clearly defined transitional policy to a Commons-based society. It is important to remember Bouckaert and Mikeladze’s (2008, p. 7) advice that 'a more sophisticated diagnosis, as a function of culture, context, and systems features' allows for 'selective transfers, for inspiration by other good practices, for adjustments of solutions, for facilitated learning by doing, for trajectories which are fit for purpose'. Hence, a fundamental belief on which this book is premised is the fact that there are no universal how-to manuals, because not only does every nation have its own special characteristics, but also rapid social change based on grandiose systemic substitutions usually has disastrous results, as history shows; many times these results are contradictory to what ambitious but benevolent revolutionaries may struggle for. Therefore, this chapter attempted to introduce suggestions and ideas for a post-capitalist society and draw attention to the promising, creative rhetoric of a PSA for Commons-oriented development. We might argue that five factors in a certain state could catalyze the transition towards a Commons-based society: i) the extended micro-ownership of fixed capital such as land, machinery and so on; ii) the need for recomposing the productive infrastructures, as is the case in defaulted states; iii) an already existent robust network of solidarity and cooperative initiatives; iv) a decentralized energy network. Further interdisciplinary research around these newly developed concepts and ideas on a global basis is imperative, along with initiating a debate between scholars and activists in order to fine-tune the transition scenarios towards Commons-oriented economies and societies.