Democratically Planned Postcapitalism

* Article: Sorg, C. (2022). Failing to Plan Is Planning to Fail: Toward an Expanded Notion of Democratically Planned Postcapitalism. Critical Sociology, 49(3), 475-493. doi

URL = https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08969205221081058

Abstract

"With the advent of digitalization, the more techno-optimist among critics of capitalism have articulated new calls for post-work and post-scarcity economics made possible by new advances in information and communication technology. Quite recently, some of this debate shifted for calls for digital-democratic planning to replace market-based allocation. This article will trace the lineages of this shift and present these new calls for digitally enabled and democratic planning. I will then argue that much of the discussion focuses on capitalism’s laws of economic motion, while rendering less visible capitalism’s social, political, and ecological ‘conditions of possibility’. To remedy this shortcoming I will ask how these fit into the recent debate and suggest avenues to extend the discussion of democratic planning in that way. Concretely, I will discuss features of a postcapitalist mode of reproduction that abolishes capital’s subordination of non-waged and waged care work. The following part will focus on both planning’s need to calculate ecological externalities and consequently determine sustainable and egalitarian paths for social and technological development on a world scale. The last section will elaborate on the ‘democratic’ in ‘democratic planning’ in terms of planning’s decision-making, multi-scalar politics, and politics of cultural recognition."

Discussion

The ‘Democratic’ in ‘Democratic Planning’

Christoph Sorg:

"There is a long tradition of critiques arguing that capitalism conflicts with democratic principles, a framing strategy still popular in more recent years (Fraser, 2015; Streeck, 2011; Wolff, 2012). Proponents of varieties of ‘economic democracy’ have classically argued that the economy itself is not a particularly democratic place. Strict hierarchies mean that workers have to follow the command of a company’s owners, who reign workplaces like autocrats. This class power and the related wealth inequality also severely limit the potential of political democracy, with economic elites having disproportionate power to influence parties and decision-making processes. Fraser (2014) adds that capitalism’s particular way of dividing ‘the economic’ and the ‘the political’ places numerous pivotal political questions outside the reach of democratic decision-making, leaving them instead to be decided by capital’s laws of motion and power relations (p. 64ff). Such decisions are not made democratically by those affected by it, but the management of companies under the influence of competition and (extremely) unequally distributed purchasing power.

The principles for postcapitalist planning outlined so far solve some of these issues. Societies no longer place their capacity for production and reproduction under the primacy of capital accumulation, but consciously plan what they produce, who produces it, how they produce it and for whom. But how to make sure that such planning is actually democratic? A popular understanding of economic democracy holds that cooperatives based on a ‘one-worker-one-vote’ principle should replace private capitalist firms. Such a principle works for issues related directly to a workplace, but the workers of a particular cooperative or sector are not the only stakeholders in economic decisions, so decision-making processes need to involve other actors, a plurality of scales, and status groups beyond the working class. Karl Polanyi for instance suggested a functional division into producer associations of different industries and a commune as the political community (Bockman et al., 2016). This system ensures a democratization of the production process via the production associations, while making sure that production aims at democratically established social goods via the commune. Prices are not set by central planners, but instead negotiated among producer associations and the commune. Commune and producer associations negotiate the ‘direction of production’ and the producer associations decide autonomously on the ‘technical-economic side of investment’ (Bockman et al., 2016: 407).

Along similar lines, proponents of Parecon have similarly envisioned democratic planning as a bottom-up process linking worker councils to consumer councils on various scales (Albert, 2003; Albert and Hahnel, 1991). Samir Amin (2013), however, suggests socializing the leading global capitalist monopolies into public institutions, which are managed by representatives of workers, consumers, the state, local authorities and other units in the value chain (p. 136ff). So a transitionary stage of socialism would appropriate the structuring power of leading corporations and democratize them by placing multiple stakeholders within them. Indeed, there is a plurality of options to ensure different stakeholders have a say in the planning process. The guiding principle might be ‘all-affected’ or ‘all-subjected’. The former means that everyone gets to participate in decision-making to the degree that they are affected by the outcome. The latter argues that everyone subjected to a particular governance structure should be involved in its decision-making, transcending both a reductionist focus on nation-states and excluding notions of citizenship (Albert, 2003; Fraser, 2008: 411ff, 2013: 202ff).

Either way, the new principle will need to reorganize the scales of politics by relegating different issues of politics to different, overlapping scales. On this issue cybernetic planning could profit from radically democratic traditions within cybernetics itself (Schaupp, 2019). Planning and decision-making need to happen on scales low enough to ensure self-management where possible and to avoid higher scales being overwhelmed with tasks and information. At the same time, issues that transcend local scales need to include higher scales to avoided exclusion of those affected by a decision. In other words: the construction of a library needs to include a different assemblage of scales than coordination to reduce carbon emissions.

In addition to this, deliberative theories of democracy hold that decision-making cannot just aggregate isolated priorities into joint decisions (Rendueles, 2021: 256ff). In Saros’s model of platform socialism elaborated above, for instance, individual consumers register their individual needs in their needs profile and thus direct the production process. While the orientation of production toward needs is pivotal, the model leaves out the social process through which such preferences are established in the first place. So a planned economy would not only need socialist laws of motion, but a truly democratic culture featuring (online and offline) spaces for exchange, within which people can engage and in the process discover their preferences (Rendueles, 2021).

A final question already implied in several issues mentioned above needs to be spelled out explicitly: how would a transition toward democratic planning impact capital’s ‘social production of difference’ (Lowe, 1996: 28; quoted after Virdee, 2019) and the related racism, sexism, homo- and transphobia, colonialism, ableism, and other intersecting forms of institutionalized discrimination? Capital and the state segment the labor force to derive value from labor remunerated below its cost of reproduction and derive stability from the fact that said segmentation prevents the working class from developing consciousness of itself in its entirety (Federici, 2004; Roediger, 2007; Virdee, 2019). Abolishing value and endless accumulation would destroy this institutionalized need to produce and reproduce difference. In the case of racism, for instance, capitalist expropriation creates the foundation for the racialized marking of subjects as targets for oppression (Dawson, 2016; Fraser, 2016). Postcapitalist production units will thus need to be designed in a way that is not driven by competitive environments to reduce its costs by any means anymore, so that they will not reproduce capital’s racialized segmentation of the labor market and colonial expropriations of foreign resources and people anymore.

However, with status-based hierarchies and colonialism being much older than capitalism, there is absolutely no reason to assume that postcapitalism would not inherit some of capital’s legacy of racism, colonialism and other forms of discrimination. Even more so since the social production of difference is not reducible to political-economic interests, but possesses a semi-autonomous logic embedded in politics of recognition (Fraser, 2013). While some forms of discrimination are related to both capitalism’s (gendered, classed, racialized, and imperial) divisions of labor and its politics of recognition, others such as of homo- and transphobia derive primarily from the latter.

This means that democratic planning of the economy is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of full liberation. Planning needs to be designed in a way that accounts for whom capital recognizes in their full humanity and who is excluded from such recognition. Concretely, the outcomes of planning need to remedy capitalism’s (and previous) legacies of injustice, it needs to be reparative in this sense. But in addition to this the planning process itself needs to be designed inclusively as well. Reparative planning would aim to heal capitalism’s unevenly experienced violence instead of merely applying a ‘universal’ perspective (Appel, 2020; Song, 2021; Williams, 2020). This is especially relevant for decommodified, universal basic services (Coote and Percy, 2020; Huws, 2021), the concrete content of which is not objectively given but needs to be subjected to democratic debate (Fraser, 2020).

A reparative, abolitionist outcome would be more likely (but not certain) if those affected by planning participate in the planning process. The section on social reproduction already mentioned Parecon’s ‘women’s caucuses’ (supported by anti-discrimination laws and affirmative action), which need to exist for multiple currently marginalized groups. We can see the need for pluralism in social and technical design in recent work and technological discrimination and design justice (Benjamin, 2019; Costanza-Chock, 2020). If AI-based systems are trained with prejudiced data they will reproduce said prejudices. From AI recruiting tools discriminating against women to facial software not recognizing darker complexion, more and more cases illustrate the problem of design injustice. If cyber-communists plan to design ‘communist software agents’ to help with democratic planning (Dyer-Witheford, 2013), these need to take into account a plurality of needs and priorities, the minority of which has a voice under really existing capitalism.

Of course the topic of design justice transcends the topic of socio-technical system design. For instance, planning in healthcare needs to be sensitive to the particular needs of women and sexual minorities, which are currently unmet. Urban planning among others needs to take into account racialized and classed histories of urban design and community construction, but also ableist design practices producing barriers to equal access. The list of examples for particular experiences of capitalism’s unevenness is long, so democratic planning needs to establish planning principles that ensure an inclusive planning process and egalitarian outcomes."

(https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08969205221081058)

Tables

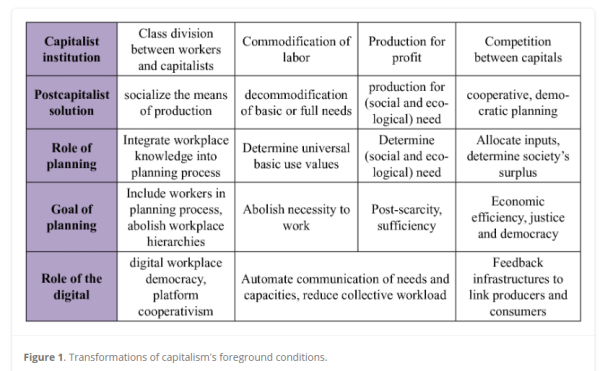

Transformation of Capitalism's Foreground Conditions

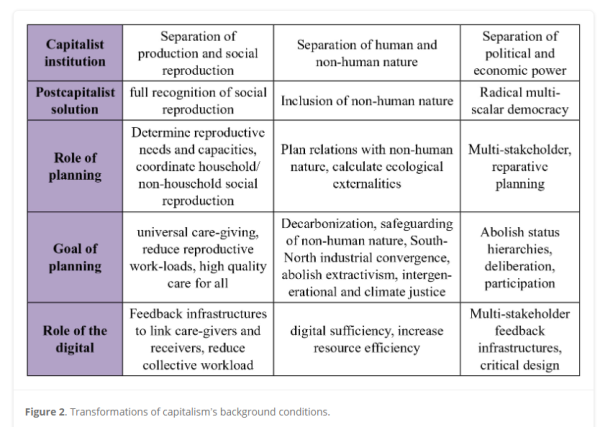

Transformation of Capitalism's Background Conditions

Excerpts

Cybernetic ‘feedback technologies’ for new forms of economic planning

Christoph Sorg:

"A series of authors have started to discuss the possibilities of such cybernetic ‘feedback technologies’ (Morozov, 2019) for new forms of economic planning in the 21st century (e.g. Phillips and Rozworski, 2019; Saros, 2014). The assumption is that big data, predictive analytics, and digital communication technologies may produce better data than market-based exchanges. These debates are by no means limited to obscure progressive circles or academic journals, with Alibaba founder Jack Ma assuming that with big data ‘we may be able to find the invisible hand of the market’ (Durand and Keucheyan, 2019) and newspapers from Financial Times (Thornhill, 2017) to Washington Post (Xiang, 2018) responding to the idea. To reconstruct the argument it is helpful to return to 20th-century socialist calculation debate, as many of the participants of this discussion do (e.g. Morozov, 2019; Phillips and Rozworski, 2019; Saros, 2014). The socialist calculation debate took place in several waves from the 1920s and 1930s up until after WWII and centered on the question whether economic calculation at scale was feasible (later: effective) in a socialist economy (Bockman et al., 2016; Chaloupek, 1990; Foss, 1993). Conventional historiography goes somewhat like this: Marxist economists such as Otto Neurath proposed moneyless socialist economies based on public ownership of the means of production and central planning of quantities of goods (Neurath et al., 1973: 123ff). Austrian economists such as Ludwig von Mises (2014) and later Friedrich von Hayek (1945) responded that central planning boards are not equipped to know where to produce which products and how much of them, let alone at the scale of an entire economy. In a market economy, Austrian authors argued, the price mechanism allocates a myriad of local information by producers and consumers, which cannot be replicated by central planners.

Already in 1979 the late neoclassical socialist Oskar Lange (1979) remarked that computers solve the complicated and numerous equations of his own method of socialist accounting ‘in less than a second’ and that the market may thus ‘be considered as a computing device of the preelectronic age’. Along similar lines, the Marxist computer scientists Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell later argued that in addition to other shortcomings of the Soviet Union ‘the material conditions (computational technology) for effective socialist planning of a complex peacetime economy were not realized before, say, the mid-1980s’ (Cottrell and Cockshott 1993). In a similar vein, Phillips and Rozworski (2019) argue that while the Soviet Union suffered from several fatal flaws, one of the more pivotal ones was that contemporary planning technology could not handle the myriad information required for a transition from the limited products of heavy industry to mass consumer products (p. 47ff).

With the advent of new computing and communication technologies, however, such considerations seem obsolete. Indeed Phillips and Rozworksi find that large multinationals already illustrate how non-market planning via new digital technologies can work in practice. They argue that if Hayek was ever correct that only a market with all its information and price signals can precipitate large-scale economic action, then enormous multinational corporations such as Walmart and Amazon should not exist. These companies and parts of their global supply chains internally engage in non-market, large-scale economic planning and nonetheless work pretty efficiently. Phillips and Rozworksi thus consider planning to be one of capitalism’s dirty little secrets.

However, any project toward a postcapitalist social order that seeks to appropriate capital’s technologies needs to keep in mind that ‘technology is neither good nor bad, nor is it neutral’ (Kranzberg, 1986) and evade the misguided belief that every problem can be overcome via technology (Morozov, 2013; Rendueles et al., 2017). Amazon does not generate the data we need for postcapitalism (Phillips and Rozworski, 2019) and any contrary assumption thus mirrors Lenin’s misguided admiration of Fordism and the German postal service, which supposedly could just be appropriated after chasing away capitalist managers (p. 95ff). Instead, transformative movements will need to push for the construction of alternative socio-technical infrastructures. A series of authors have made some preliminary suggestions of what alternative futures based on these could look like."

(https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08969205221081058)

Post-Capitalist Planning

Christoph Sorg:

"Cockshott and Cottrell (1993) propose a centrally planned economy linked to participatory democracy, which could now profit from the technological innovations elaborated above. Their proposals discuss the possibility of accurate planning and solving equations by central planning boards, but less on the need to democratize and decentralize the planning process itself. Decentralized and participatory planning is most famously associated with ‘Participatory Economics’ (‘Parecon’), which brings together worker councils and consumer councils to collectively negotiate economics plans (Albert, 2003; Albert and Hahnel, 1991). Nick Dyer-Witheford (2013) comments that Parecon needs to watch out that it does not turn endless meetings, which is why he suggests complexity reduction via new technologies. ‘Communist software agents’ (p. 11ff) would semi-autonomously develop economic proposals, which are then be discussed, revised, and decided up on social media platforms as digital fora for democratic planning.

Such a form of cybernetic planning would follow less in the footsteps of Soviet top-down planning, but revive heterodox legacies of economic democracy that are rendered illegible in readings of the calculation debate as a binary conflict of Austrian versus Marxist economists (Bockman, 2011; Bockman et al., 2016). The experiments with cybernetics and democratic socialism in Chile’s ‘Project Cybersyn’ are particularly important (Medina, 2011). The administration of Salvador Allende invited British cybernetician Stafford Beer Chile to aid with a socialist transformation of the Chilean economy. Project Cybersyn established a computer network using the limited telecommunications technology of 1970s Chile, which connected factories to a central computer in Santiago via telex machines. When the system detected a problem, it was supposed to be solved on the local firm level and only successively reached higher levels (branch, sector, overall) after a limited timeframe if this was not possible. Eventually, such bottom-up planning was supposed to include consumers as well, but the project abruptly ended with the 1973 military coup before more experience could be gathered. Nonetheless, cybersyn hints at new possibilities of democratic-decentralized planning in an age of digitalization (Morozov, 2019).

One of the most sophisticated and detailed elaborations of such democratic-decentralized-digital planning comes from radical economist Daniel Saros (2014), who was in turn heavily influenced by the work of Parecon. Saros departs from the assumption that in Marx’s time the technological level of development was not sufficient for a genuinely socialist law of motion. By this he does not mean computing power to solve complicated equations, but cybernetic feedback technologies to facilitate democratic-decentralized planning in what could be termed platform socialism. In Saros’s (2014) model, consumers plan by putting the products they want for the next production cycle from a ‘general catalogue’ of use values into their digital ‘needs profile’ (p. 174). In this way, Saros’s socialist laws of motion depart from the needs of the consumers instead of the anarchic production competition of the marketplace. If consumers later want to consume products they didn’t ‘plan’ that’s still possible, just slightly more expensive, thus rewarding participation in planning (Saros, 2014: 175). Consuming less than the average consumer is rewarded as well because it shortens the collective need to work (Saros, 2014: 176).

Depending on which products consumers picked from the general catalog, worker councils receive points and can in turn register their needs for inputs in the catalog (Saros, 2014: 177ff). Predictive analytics may help analyze deviations of communicated needs from actual consumption patterns, while cybernetic management could analyze macro-flows to avoid bottlenecks or regional input shortages. Worker councils are self-managed by all workers in a certain production unit. They have ‘legal guardianship’ over the means of production they use, but don’t own them, which means they cannot just sell them (Saros, 2014: 182). The workers receive a base income, which increases with experience in the same line of work, but is divorced from the performance of the council (Saros, 2014: 185). These ‘credits’ are not money and thus cannot be traded (Saros, 2014: 188f). Instead of seeking profits, workers are motivated to distribute their goods. If demand is lower than expected, they can reduce the price to get rid of surpluses. However, if they don’t use the points they received to satisfy consumer needs, they are less likely to receive the same amount of production points in the next cycle.

Such a platform socialism suggests socialist laws of motion and accordingly abolishes a series of capitalist institutions.

Nancy Fraser (2014: 57ff) sees four interrelated institutions constitutive of a capitalist economy in the Marxist sense:

- private property of the means of production linked to a division between those who live off their labor and those who life off profits (1),

- ‘free’ workers that are both free in a legal sense, but also free to starve if they do not sell their labor (2),

- competition driving the endless accumulation of capital (3),

- and a particular role of markets, which includes both a commodification of input factors and markets determining society’s use of surplus capacities (4).

Saros’s platform socialism gets rid of privatized means of production (1), the endless quest for profit (3), and consumer planning now drives the direction of social production (4). Markets for input goods do not constitute generalized markets in the capitalist sense, since they can only be exchanged for production points and not be traded in general. Workers still have to exchange their labor time for credits to purchase goods (2), a principle that has been criticized by some (Groos, 2021; Sutterlütti, 2021). While Karl Polanyi left open whether goods should be distributed according to ‘work performance except in the area of basic needs’ or according to need (Bockman et al., 2016: 393), Karl Marx suggested that the principle of ‘to each according to their work’ must eventually be surpassed by ‘from each according to their ability, to each according to needs’, a position that Saros (2014: 38, 207) holds as well. So even if accounts differ on concrete trajectories, they at least agree ‘from each according to their ability, to each according to needs’ is a desirable end goal and that some basic needs should not have to be traded against labor time.

The new cybersocialists have much to say on what postcapitalist economic laws of motion could look like and the debate has fortunately continued since the seminal texts elaborated above (e.g. Arboleda, 2021; Fuchs, 2020; Jones, 2020). Unfortunately, however, they are frequently much less clear on what Fraser (2014) would call capitalism’s social, ecological and political background conditions of possibility: social reproduction (5), non-human nature (6), and political institutions (7) (p. 60ff). They all emerged when the emergence of capitalism broke up feudalism’s traditional livelihoods and thus divorced production from reproduction, society from nature, and economy from polity. Capitalist laws of motion render these background conditions invisible and treat them as infinite, but the system at the same time pivotally depends on them. The violence inscribed into them derives not primarily from the exploitation of wage labor via commodity production, but from the oppression, dispossession, and destruction of women and sexual minorities, racialized/colonized groups, and non-human nature (Federici, 2004; Fraser, 2014; Mies, 1986; Patel and Moore, 2017; Robinson, 2000; Virdee, 2019).

Such a perspective expands the question of how to democratize or abolish markets by an additional question of how to make sure such a transformation empowers all groups that never had equal access to the market to begin with—and it adds non-human nature to the equation. There is no reason to assume that a postcapitalist transformation could not abolish some if these institutions, while leaving others intact. Although Soviet state socialism is by no means a model for the new advocates of economic planning, the system’s productivism, Soviet women’s double burden, continued racism, anti-Semitism, and colonialism despite proclaimed internationalism may serve as a warning that planned economies are in principle just as compatible with androcentrism, anthropocentrism, and ethnocentrism. A social and democratic postcapitalism that does not wish to perpetuate these capitalist shortcomings by focusing only on capitalism’s economic institutions would thus also need to center on the ‘nurturing of people, the safeguarding of nature, and democratic self-rule as society’s highest priorities’ (Fraser, 2020: 10). Along these lines, the next part will discuss trajectories for postcapitalist forms of reproduction, political ecology and multi-scalar democratization compatible with a transformation to postcapitalist planning."

(https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08969205221081058)

Expanded Notions of Postcapitalist Planning

Universal Care-Giver

Christoph Sorg:

"Fraser (2013: 134ff) elsewhere suggests the ideal of a ‘universal care-giver’ to replace the ‘male breadwinner’ at the heart of capitalist patriarchy. Transformative approaches should not idealize the masculinized model of wage work and encourage care-givers to seek freedom in wage labor, thus extending principles of capitalist productivism (Fraser, 2013: 123ff), which in reality is subsidized by racialized global care chains in the first place. Neither should they be happy with mere social subsidies for care-givers, which might upgrade reproductive work, but, at the same time, further cement the gendered division of labor (Fraser, 2013: 128ff). Instead, they should encourage cis-men to take on more reproductive tasks, take paternity leave, work part-time and so on, thus converging masculinized breadwinner and feminized care-giver into universal care-giver (Fraser, 2013: 133ff)."

(https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08969205221081058)

Post-work perspectives on reproduction

Christoph Sorg:

"Hester and Srnicek (2018) expand on these ideas by suggesting a post-work perspective on reproduction (p. 363ff). This includes a ‘critical technopolitics of the home and other places of social reproduction’, which neither uncritically celebrates the ‘roboticization of social reproduction’ nor romanticizes care work as ‘an expression of the (gendered) self or a personally rewarding pastime’ (Hester and Srnicek, 2018: 364). In other words: access to dishwashers and washing machines for everyone and an economic turn to plan for technological devices that actually reduce overall reproductive workload (and are ecologically sustainable, one should add). Second, Srnicek and Hester suggest to lower domestic standards. They argue that the development of labor-saving household devices has not increased leisure time, but instead raised social expectations of how much time should be dedicated to cleaning the home, preparing or socializing one’s children, and so on (Hester and Srnicek, 2018, 365). The third and final proposal is to transform living arrangements currently centered on the assumed nuclear family. Larger communities could profit from reproductive economies of scale and profit from collective kitchens or workshops (Hester and Srnicek, 2018: 366).

Srnicek and Hester stress that they wish to leave open space for different ways of life, since some see work on the household as a source of personal fulfillment whereas others do not. Along similar lines, Saros (2014: 187) suggests that in his model ‘household labor and child rearing services may be registered as a need’ or families may ‘prefer to perform this work themselves’. While he does not further elaborate how this would work in practice, Parecon advocates Bohmer et al., (2020) develop a far more detailed set of related suggestions. They distinguish universal access to education and healthcare provided by the public, reproductive services provided by self-managed worker councils, and household care and socialization work. People have a right to choose between doing reproductive tasks themselves in their households or having it done by others, with the notable exception of mandatory primary and secondary education provided by the public (Bohmer et al., 2020: 12). If household member choose to provide infant, pre-K, disabled, and elder care themselves, they should be treated as ‘off-site’ workers of the education or healthcare system and remunerated according to a democratically decided standard payment. The quality of care is a delicate issue and should be monitored by a public social service agency."

(https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08969205221081058)

Balanced Job Complexes

Christoph Sorg:

"the Parecon principle of ‘balanced job complexes’ overlaps with Fraser’s universal care-giver, as it advocates workers taking on different tasks to combat hierarchies arising from divisions of labor. The authors also suggest caucuses for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersexed community, people of color, and people with disabilities to tackle other forms of discrimination. Unequal distribution of reproductive tasks within households is harder to confront and at the same time, needs to be balanced with concerns for privacy. However, women’s caucuses in neighborhood councils could provide moral support for women, cooking and cleaning classes for men and combat gender biases in consumption decisions."

(https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08969205221081058)

Movements

Post-Capitalist Ecomodernism

Christoph Sorg:

"Postcapitalist imaginations of the post-capitalocene range from eco-modernist techno-optimism to degrowth and eco-socialism, with a plurality of stances in between. Socialist eco-modernists tend to assume that humans notoriously struggle to imagine exponential developments (e.g. Bastani, 2019: 40ff; Rifkin, 2014: 79ff), as virologists recently found when trying to warn the public of exponential growth of infections during the Covid-19 pandemic. They thus argue that we tend to underestimate the potential of technological innovation—just like sophisticated speech recognition (e.g. Reddy, 2004) and self-driving cars (e.g. Levy and Murnane, 2004: 24ff) seemed like absurd science fiction in the early 2000s. From the postcapitalist eco-modernist perspective this creative human potential needs to be liberated from such capitalist institutions to harvest it for the struggle to avoid climate disaster. Postcapitalist degrowthers and eco-socialists, however, depart from the observation that technological innovation (under capitalism) tends to increase output instead of producing the same amount with less resources (e.g. Hickel and Kallis, 2020). They thus call for sufficiency-based economics, at least in classes and regions of the world that claim a disproportionate share of our global carbon budget and finite resources. While these positions are in principle compatible, distinct assumptions about the potential of technology tend to entail drastically different imaginaries about what a sustainable and decarbonized postcapitalism could look like.

Postcapitalist eco-modernists envision a world of abundance built upon the foundation of low-carbon energy sources such as solar, hydro, and wind, with some disagreement existing over the role of nuclear (e.g. Jacobin, 2020). In such a world, the increasing demand for lithium, nickel, cobalt, rare-earth elements, and other material would eventually be covered via asteroid mining (Bastani, 2019, 117ff). Accelerating computing power, AI, and free information would successively reduce the overall amount of work (Rifkin, 2014; Srnicek and Williams, 2015), while synthetic meat and cellular agriculture fill our plates with cruelty-free, low-carbon food (Bastani, 2019). In addition to renewable energy sources and the end of industrial meat production, zero-emission flights and high-speed trains fix another high-carbon sector of our current economy.

The postcapitalist-modernist project is to prevent capitalism of getting in the way of such a futurist utopia. Srnicek and Williams (2015) suggest an acceleration of technological progress via full automation, universal basic income, reduced working hours and a cultural shift away from the work ethic, thus making sure companies have every incentive to automate and that the remaining work is spread evenly among workers (p. 107ff). Phillips and Rozworski (2019) suggest a socialist anthropocene that democratically plans the earth system to deal with climate change (p. 240ff). Such planning would need to put decarbonization and technologies to help a transition toward a low-carbon or even negative-carbon economy on the top of its list of priorities (Phillips, 2015). Without such democratic planning fossil capital and irrational markets left to their own devices would precipitate a climate catastrophe. Aaron Bastani (2019) elaborates a more concrete transformative program, which features socialized finance on the local, national, and international scale as key institutions to fund and direct a transition into postcapitalism (p. 217ff). In addition to worker-managed businesses and universal basic services, such directed finance could facilitate an energy democracy based on decarbonization.

Concretely, national energy investment banks are supposed to fund local energy cooperatives, carbon-neutral/-negative buildings and smart energy systems to reduce unnecessary energy consumption. To account for global inequality and the Global North’s climate debt, an ‘International Bank for Energy Prosperity’ capitalized by taxes on Northern CO2 emission would fund energy transition in the Global South."

(https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08969205221081058)