Cap and Share

Report: Cap and Share. A fair way to cut greenhouse gas emission and tackle climate change

URL = http://capandshare.org [1]

Full pdf version via http://www.feasta.org/documents/energy/Cap-and-Share-May08.pdf

Abstract

Drastic cuts in the world’s greenhouse gas emissions are required to avoid a climate catastrophe. An international treaty to secure such cuts will be impossible to agree unless the responsibilities involved are shared around the world on an equitable basis. Moreover, that sharing system must be robust enough to ensure that the cuts agreed actually happen. Cap and Share (C&S) is both robust and equitable. It has the additional advantage that, until it is adopted globally, it can be used by countries and regions to set their own emissions on a downward path. Cap and Share provides a framework that scales from the personal and local to the regional and global. We can start building a global system step-by-step now.

Source: http://capandshare.org

Executive Summary

Drastic cuts in the world's greenhouse gas emissions are required to avoid a climate catastrophe. A worldwide agreement to secure such cuts will be impossible to negotiate unless both the pain and the benefits are shared equitably around the world. Moreover, the sharing system must be robust enough to ensure that the cuts agreed actually happen. Cap & Share is both robust and equitable. It has the additional advantage that, until it is adopted globally, it can be used by individual countries to make sure their emissions take a downward path.

Cap and Share was developed to meet the twin challenges presented by climate change and the peak in the world supply of easily-extracted oil. It is a variant of cap and trade and would limit the use of coal, gas and oil. It can, however, be used to share the benefits from using any scarce natural resource. It works by placing a cap on the use of the scarce resource and charging the users whatever price is necessary to balance their demand with the capped supply. The receipts from the resource users are then shared on an equitable basis amongst all those with an interest in the resource involved.

This paper deals with the use of C&S to deal with oil peak and climate change. If it were to play that role globally, C&S would cap world fossil fuel greenhouse emissions and then tighten the cap year by year at a faster rate than oil production was decreasing. This would make the emissions tonnage set by the cap a scarcer resource than the oil supply. As a result, the whole of the extra amount that users would have been forced to pay the producers for supplies of the scarce oil would be captured in the price paid for C&S emissions permits.

The captured money would then be shared amongst those with a claim on the capped scarce resource and, since that resource is the limited capacity of the sky to act as an emissions dump, everyone on Earth would have an equal claim and thus get an equal share. The emissions permits would also be scarcer than the supply of coal and gas, so C&S would capture the extra that people were prepared to pay to use them too.. This extra is what economists call the "scarcity rent". After some deductions which are explained in this paper, C&S would then share the total rent from the three fossil fuels amongst everyone on the planet.

The first paragraph mentioned charging resource users for their use of a scarce resource. Under Cap and Share, these charges are collected indirectly. The emissions permits are not sold to fossil fuel users - that would be difficult because there are billions of these. Instead, they are sold "upstream" to companies introducing fossil fuels to the global economy. As only a small number of firms produce most of the fossil fuel used in the world, this makes C&S easy to administer. Each producer is required to acquire enough permits to cover the eventual emissions from the fossil fuels they extract.

Of course, the fuel firms have to add the cost of the permits to their prices and this puts up the cost of everything sold because all goods and services have an energy content. However, anyone who uses, directly or indirectly, rather less energy than is produced from the fuel burned when their share of each year's capped emissions is released is likely to receive more money from selling their permits than their cost of living goes up. As a majority of people in the world manage on less than the average amount of energy used per person, most people would gain financially from the use of C&S. This would make C&S popular and therefore politically robust.

The paper argues that C&S needs to be adopted urgently not just for climate reasons but because the scarcity rent being captured by fossil fuel producers is concentrating global wealth in a way that threatens to collapse the world economy. The payment of scarcity rent is already causing severe hardship for millions of poorer people around the world.

The paper describes the way C&S could be used as the operating system for the fossil fuel part of a global climate agreement. Other systems are going to be needed to enhance greenhouse gas sinks and conserve the stocks of carbon held in soils and plants. The various options that could be incorporated into the design of C&S are described and the paper looks at the changes that would be required in other systems, such as the money-creation system, for C&S to work well. The paper ends with an account of the steps being taken to get C&S adopted internationally, and stresses that before this can happen, the concept needs to gain massive public support.

Cap and Share seeks to provide a simple, workable and ethical economic framework for dealing with the climate crisis. It is based on the belief that every human being has a right to an equal share of the fees that fossil fuel users would be prepared to pay for the right to discharge greenhouse gases into the global atmosphere.

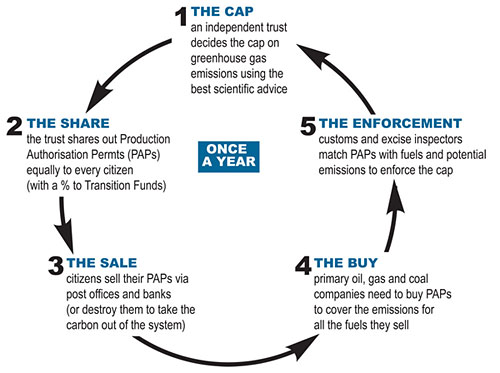

Under C&S, global emissions would be capped at their current level and then brought down rapidly year by year. Each year, the tonnage of emissions that the world community decided that it could risk releasing over the following twelve months would be shared equally amongst the Earth's entire adult population. Each of us would actually receive a "fossil fuel pollution authorisation permit" (PAP) conveying the right to our individual share of that year's global emissions and making us responsible for it.

The important thing to note about these permits is that they would not ration our personal energy use. Instead, they would permit fossil fuel production. They would be valid for a year, during which people would sell them to financial intermediaries such as banks and post offices, who, in turn, would sell them on to oil, coal and gas producers. These producers would need to acquire enough permits to cover the carbon dioxide emissions from every tonne of fossil fuel they sold and international inspectors would check to ensure they did.

Cap and Share is clearly equitable and, arguably, fairer than any other practical method of sharing out rights to emit around the world. It would also be robust because, as the tonnage of emissions being distributed was reduced year by year, the market value of each person's permit allocation would increase, ensuring that poorer people received an income from the sale of their permits which enabled them to buy food and fuel as these became increasingly expensive. Since the reductions required in fossil fuel use to avert a climate catastrophe are so rapid and deep, adopting some other greenhouse gas control system that failed to protect the poor would cause serious injustice and provoke massive opposition. C&S provides an orderly way of managing the transition from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources with the market setting the price at which the right to emit is sold." (http://www.feasta.org/documents/energy/Cap-and-Share-May08-summary.htm)

Detailed Treatment

This comes from a different source, see Commons Action for the United Nations:

“Cap, Auction and Dividend” on an Input Basis, (Cap and Share)

Summary

Key Message:

All the necessary technology and finance are available to solve the climate problem (EISENBEISS 2008) and at the same time, mankind harvests food sufficient for 12 billion people. Nonetheless, one billion out of seven billion people are starving and the climate is changing. How can we design a global economic policy that prevents climate change and at the same time makes the economic value of the atmosphere as a global common good available to its owner, i. e. to each individual per capita?

The proposed mechanism is a „cap, auction and dividend“ model.

1.) Emission rights are not granted by nation but globally auctioned, i. e. by a UN body. The revenue is

2.) granted per capita individually and directly. Banking facilities are being made available and affordable globally by the implicit support for micro-finance systems.

3.) Economically developing countries and economically developed countries alike can proceed on their trail of growth, and economically less developed countries can through the influx of purchasing power (to the people, not to the potentate) embark on such a trail of growth. The limitation per capita allows for a smooth and effective path for reducing emissions over decades.

4.) Focusing on the main cause for global warming, fossil fuels (oil, coal, gas), allows for input orientation: Whenever a ton of these is being sold into the economic cycle, an equivalent amount – of roughly three tons – of emission rights must have been purchased before (EISENBEISS 2007a).

Abstract:

Constraints and Operating Levels in International Climate Change Prevention

There are three major constraints for international climate protection:

1.) The emission of greenhouse gases is to be limited globally (PFEIFER 2011).

2.) The emission absorption capacity of the atmosphere as a “resource” must be used efficiently. Therefore, the resource should possess a global price.

3.) A world-wide per-capita solution is required, as agreed by German Chancellor Merkel and Indian Prime Minister Singh in 2007. Countries like China and India, whose participation is vital for climate change prevention, could otherwise not agree to join, as their economic growth does not allow them to reduce emissions compared to 1990 (Kyoto).

An approach from Institutional Economists (3-Level-Model):

1. Level (Sufficiency):

Determining the maximum allowed level of global emissions (per annum) as a limitation (“Cap”).

2. Level (Efficiency):

Globally auctioning off the permitted volume determined on level one. Input orientation: Since the amount of CO2 for each combusted carbon molecule is known, sellers of carbon (e. g. contained in oil and coal) must purchase an equivalent amount of emission rights (EISENBEISS 2008).

3. Level (Equivalence):

The proceeds from level two are paid out per capita globally – for instance by a UN body.

Design and Challenges

The first two levels represent the known cap & trade model. Through the third level, the model responds to claims by German Chancellor Merkel and Indian Prime Minister Singh for a per-capita-solution, allowing China and India to join and in their own interest. In July 2008, negotiations on climate change prevention during the G8 summit failed, because India and China refused to accept the proposed policies due to a lacking percapita- solution as it is outlined in this paper.

How can a global payout be realised? In developed economies, the payout or bonus can be paid to the clearing account corresponding to the personal tax number. Owing to a spreading microfinance system, also inhabitants of poor countries increasingly have access to banking services.

In countries where this is not the case, the money could go to local governments to make sure people are fed and to install banking systems.

In the case of corrupt regimes, the money for the population should go to UN bodies, for instance the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), to ensure the minimum food and water supply to those in need.

How can global suppliers of fossil fuels be made to agree? By their governments. The economic argument is: since the obligation to purchase emission rights prior to the sale of fossil fuels hits all suppliers, it represents an increase of factor costs and will be – like all other costs of production and like all other climate measures – carried by consumers. Those consumers using less than average amount of a resource, will receive a financial net benefit through the disbursement (third level).

Political and Economic Implications

The application of such a model systematically ensures that climate protection parameters are observed globally and that CO2 is used efficiently. The model enforces financial incentives for innovative technologies and both research and entrepreneurial initiative in climate protection. National governments can abstain from trying to manipulate climate prevention measures on an operational level (such as through administrating low energy house and car programs etc.) and rather focus on a framework setting – an ordoliberal approach.

A single emission price, globally, provides corporations with increased planning reliability and secures jobs. Corporations are not forced to relocate production due to unequal emission and climate protection regimes. Because it does not increase costs in a single economy locally, it does not distort international competitiveness of a single nation.

Emission rights are being purchased by those who have the highest avoidance costs and those corporations who produce the highest economic benefit for their customers by applying the most efficient use – expressed through the ability to pay the highest auction price.

Climate protection does not only become economically beneficial but also democratically feasible, as consumers do not fear to lose access to goods and services through increased prices.

An emission price of 40 to 50 US-Dollars per each of the allowed 20 to 30 billion tons would yield a payment of about 12 to 14 US-Dollars per capita globally. For the poorest, this results in the abandoning of hunger.

More Information

- five minute video intro: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSUuFjAOZUo&feature=player_embedded#!

- Cap & Share: simple is beautiful (chapter from Feasta's book, Fleeing Vesuvius.