2.3 Economics of Information Production

Industrial and Networked Information Economy

For the last 150 years the economies of the more advanced nations have been mainly industrial economies. The Industrial Revolution has led to the cheap mass manufacturing of physical goods where producing 100 or 100'000 copies of a product costs nearly the same. As in the 20th century information was also mainly distributed through media with high up-front costs, like broadcasting or physical records and prints, and information production wasn't quite cheap, the industrial information economy produces content for an audience as large as possible to gain more profit per-copy.[1] This led to the rise of the mass media and the commercialization and concentration of information production. (2.1 Copyright and Mass Media)

However, with the advent of the personal computer and the internet, the capital necessary to produce and distribute information is now widely available to millions of people. These are the prerequisites for the emergence of the networked information economy.[2] These changes come at a time when especially technical products grow ever more complex and more of the value of a material product is contained in the information it carries, rather than its material substance.[3] Thus the focus of economies in industrialized nations is shifting from manufacturing goods to information production, as cheap labour is available in emerging markets like China, and the issue only gains in importance.

'Intellectual Property'

In most countries, there exist a lot of different laws today concerning entitlements attached to certain names, written and recorded media, and inventions. The most important are copyright which is meant to regulate copying, patents that are meant to prevent others from practicing an invention, and trademarks which make sure a distinctive sign or indicator that is used to identify an organization's product as its own, is not used by other businesses. The controversial umbrella term intellectual property is often used to lump all these different laws together. In recent years, we have observed calls to ever stronger intellectual property rights arguing that they encouraged innovation. Jack Valenti, long-time president of the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) and one of the most influential pro-copyright lobbyists in the world, formulated what he considered 'the fundamental issue' simple: Creative property owners must be accorded the same rights and protection resident in all other property owners in the nation.[4]

This claim is intuitively plausible, because it's simple. But it ignores one significant fact which the misleading term intellectual property already implies: Intellectual works are not analogous to physical property. A song is not the same thing as a chair. What we call intellectual works, or ideas is ultimately information. For example knowledge written down in a book, or virtually anything that can be digitally represented as a series of zeros and ones - be it text, sound, video or virtual 3D objects - is information. And information is a nonrival good. That means that it can be used by one person without preventing others from using it simultaneously. If I sit on a chair, nobody else can (comfortably) sit on the same chair at the same time. But if I watch television, this doesn't prevent anybody else from watching television too. What is more, with digital technology huge amounts of information can be copied without consuming anything but a tiny bit of electricity. That's the difference between stealing a chair from my neighbour and downloading a song from another computer. My neighbour can't make use of the chair anymore, because it isn't there anymore, whereas the song was copied and resides now on both computers - joy shared is joy doubled.

The other distinct quality of information is that existing information itself is a prerequisite to produce new information. It is difficult to invent a bicycle if the basic invention of the wheel is not known. That's why the simple logic currently held by most governments doesn't deliver. It says that ever more exclusive rights like copyright and patents will lead to more innovation, because innovators have greater incentive to innovate as they can then make exclusive use of their invention. But many potential inventors are locked out from innovating because they can't pay for yesterday's information.

When information is given away for free, this is to the best of society's overall welfare because that way many more people can profit from it. As information is nonrival, this doesn't hurt anybody if there is enough incentive to produce information in the first place.

Patents

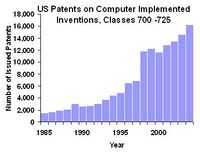

In today's complex products, much information needed to understand or improve them is designated 'property' of various entities. For example a DVD player contains about a dozen devices that are patented by different companies. A single microchip can contain over 5,000 different patents.[5] As of 2005, there are over 1.5 million patents in force only in the United States.[6] Thus, further innovation in many industries is only possible with access to a large number of patents. It can be very expensive to get certain patents licensed from their owner which has the consequence that certain new inventions that rely on patented information are never produced. And because it is expendable to identify the needed patents and license all of them one by one, many companies use cross-licensing agreements which basically say that each company has full access to the other's patent portfolio. This locks out small innovators and leads to a concentration of information property. Thus law relying heavily on exclusive information property rights shapes business practices, favouring exclusive-rights-based strategies of closed companies rather than nonproprietary ones where a large community forms around a pool of commons-owned information as for example in free software projects.

In order for an issued patent on an invention to be granted it has to meet certain criteria: [7]

- The invention or discovery of a new and useful process must lie within patentable subject matter, for example scientific theories, mathematical methods or aesthetic creations are not patentable.

- The invention must be novel,

- It must be non-obvious (in United States patent law) or involve an inventive step (in European patent law),

- and be useful (U.S.) or be susceptible of industrial application (Europe).

When a patent is filed, the patent office has to consider whether it is valid under these criteria and can then grant the patent. It is then in force for usually 20 years from the filing date, provided the patentee pays the renewal fees, generally due each year.

Patents are meant to encourage innovation. In some industries this aim may be achieved with patents, in others this is highly questionable. Especially software patents are under heavy fire at the moment. While they are allowed in the United States, in the European Union it is held that software isn't patentable as such. In the rapidly developing field of software development, many techniques that have been granted a patent by the patent office are all too obvious to most developers and while writing software they always have to fear that they infringe on some patent that they didn't even know existed and then get sued.[8] It is virtually impossible to develop software without hitting a patent sooner or later. Software companies are thus forced to acquire a large patent portfolio of their own in order to countersue a competing company that might chose to sue them for infringement, something that isn't possible for small developers. Additionally, patents on file formats hinder implementation of these formats in other programs and thus prevent interoperability, forcing consumers to use only one program and many free and open source software projects that operate at practically no budget can't pay for patent licensing. Also patents in other industries, especially patents on human genes, are highly disputed and in medicine they often prevent cheap generic drugs that might be badly needed by the poor of the world.

Most firm managers don't see patents as the most important way to capture the benefits of their research and developments and most innovation doesn't come from businesses relying on exclusive rights, but from nonmarket sources (both state and private) and market actors whose business models do not depend on the protections of intellectual property.[9]

Exclusive Rights in a Digital World

The three primary inputs needed for information production are existing information, mechanical means of production and distribution, and human communicative capacity.[10] With computers and the internet, the costs of the second category are now radically low. While exclusive rights do encourage information production on a limited scale as the expected benefit is greater, they do primarily stifle information production as the up-front cost of obtaining the information necessary to further innovate is higher. If existing information wasn't locked down by 'intellectual property law', with computers and the internet being the only resource left narrowing informational and cultural production would be human communicative and creative capacity. But as it is now, laws are hindering the potential of the networked information economy. In the next chapter, the workings of the networked information economy are being looked at.

References

- ↑ Benkler, Yochai; The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom, 2006, p. 32

- ↑ Benkler, p. 3

- ↑ Towards a free matter economy (Part 1): Information as matter, matter as information, Terry Hancock at the Free Software Magazine

- ↑ Quoted from Lessig, Lawrence; Free Culture, 2004, p. 117

- ↑ Wikipedia:Tragedy of the anticommons, 29. July 2007

- ↑ Patents in Force, WIPO

- ↑ Wikipedia:Patentability

- ↑ Fighting Software Patents - Singly and Together, Richard Stallman

- ↑ Benkler, p. 40-41

- ↑ Benkler, p. 52