Mutualizing Urban Provisioning Systems

* Article: Commons Economies in Action: Mutualizing Urban Provisioning Systems, By Michel Bauwens and Rok Kranjc

URL = https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Mutualizing_Urban_Provisioning_Systems PDF

In: P2P: TOWARDS A COMMONS ECONOMICS By Michel Bauwens, Jose Ramos and Rok Kranjc, P2P Foundation, 2020, Part 3.

Reformatted for the wiki with minor corrections by Simon Grant, January 2021.

1. Introduction to the Commons and P2P Dynamics: The Basic Concepts

1.1 The commons and P2P dynamics

The commons are most often defined in the following way,[1] according to three separate criteria:

- The commons are a set of shared resources, which can be material (physical) or virtual (i.e. digital resources representing human knowledge and culture). This means that the commons are first and foremost also a social object, inherited as part of the web of life, or constructed specifically by human communities.

- “There are no commons without commoning”: the commons are a form of governance by human communities; the shared resources must be maintained, produced or managed by such communities or stakeholder alliances. This introduces the notion of choice: a “resource” is a commons only if it is managed collectively, thus differing from public and state goods, as well as private goods.

- From this follows the third criteria: the commons are regulated through norms and rules that have been instituted by the community itself, even if they must compose with private property and public power.

More recent ecological thinking has problematized divisions between humanity and resources, which should be seen more as an interconnected web of life characterized by cooperation between species and ecosystems. However, in our opinion, this does not invalidate the three criteria, but stimulates us to think of each of them in a new way, for example by recognizing juridical personhood for certain non-human entities, or recognizing the legitimacy and interplay of non-human concerns in any socio-economic design, urban planning and development (Schönpflug & Klapeer 2018; Metzger 2015); it enriches them by accepting “extra-human natures” – entities, communities and whole socio-ecological metabolic systems – as Earth’s stakeholders and agents in a (transitioning towards a) commons-based system.

Urban commons refer to those commons that exist in an urban environment, for example shared mobility, shared housing, food, energy, open source protocols, designs and infrastructures. They involve the mutualization of provisioning systems at the level of the city.[2] In this context, they may concern the City governments and administrations, as they exist within the regulated space of the city. But they can also be considered, as proposed by Iaione (2016) and Foster and Iaione (2016), as a governance model for cities themselves, to the degree that a city can be considered a shared resource for all its citizens and inhabitants. In this instance, innovating with multi-stakeholder models of governance emerges as a potential part of city governance.

We believe that it is also useful to consider urban commons in a historical context, that of the evolution of the commons itself, as a human institution in the political economy (see Box 1).

|

Box 1: The history of the commons before, during and after the political economy of capital Class-based societies that emerged before capitalism have relatively strong commons – essentially the natural resource commons, studied by the Ostrom school. They coexist with the more organic culturally inherited commons (folk knowledge, etc.). Though pre-capitalist class societies are very exploitative, they do not systematically separate people from their means of livelihood. Thus, under European feudalism, for example, peasants had access to common land. With the emergence and evolution of capitalism and the market system, first as an emergent subsystem in the cities, we see the second form of commons becoming important, i.e. the social commons. In Western history, we see the emergence of the guild systems in the cities of the Middle Ages. Guilds are solidarity systems for craft workers and merchants, in which “welfare” systems are mutualized and self governed. When market-based capitalism becomes dominant, the lives of the workers become very precarious, since they are now divorced from the means of livelihood. This creates the necessity for the generalization of this new form of commons, distinct from natural resources. In this context, we can consider worker cooperatives, along with mutuals and other examples, as a form of commons. Cooperatives can then be considered a legal form to manage social commons. With the welfare state, most of these commons were state-ified, i.e. managed by the state, and no longer by the commoners themselves. This means that under a capitalist political economy, the commons tend to be marginalized, either by the private sector or by the state. Since the emergence of the internet, and especially since the invention of the web (marked by the launch of the web browser in October 1993), we see the birth, emergence and very rapid evolution of a third type of commons: the knowledge commons. The emergence of this practice of “knowledge as a commons” coincides with the strong resistance to the second enclosure of the commons, due to neoliberal intellectual property practices, and to free software itself, which is both a resistance against privatisation, and a construction of new commons. Distributed computer networks allow for the generalisation of peer to peer dynamics, i.e. open contributory systems where peers are free to join in the common creation of shared knowledge resources, such as open knowledge, free software and openly shared designs. Knowledge commons is bound to the phase of cognitive capitalism, i.e. a phase in which knowledge becomes a primary factor of production and competitive advantage. In this conjuncture the commons represent an alternative to “knowledge as private property’, in which knowledge workers and citizens take collective ownership of this factor of production. To the degree that cognitive or network-based capitalism undermines salary-based work and generalized precarious work, especially for knowledge workers, these knowledge commons and distributed networks become a vital tool for social autonomy and collective organisation. But access to knowledge does not create the possibility for the creation of autonomous and more secure livelihoods, and thus, knowledge commons are generally in a situation of co-dependence with capital, in which a new layer of capital, netarchical capital, directly uses and extracts value from the commons and human cooperation. But we should not forget that knowledge is a representation of material reality, and thus, the emergence of knowledge commons is bound to have an important effect on the modes of production and distribution. A ‘phygital’ phase has been reached, in which we see the increased intertwining of ‘digital’ (i.e. knowledge) and the physical. |

Understanding contemporary commons also requires an understanding of “peer to peer dynamics”. Peer to peer is a term that was used during the emergence of a new type of digital network, where computers could interact with any other computer, bypassing the need to go through centralized servers. To a substantial degree, the early internet was inspired in its design by such principles. But note that this is also a social dynamic, i.e. any dynamic where humans can freely connect, interact, and even create value together, without necessarily being in close proximity with each other, can be considered a peer to peer system, sometimes despite the fact that such a network can be privately owned and governmentally owned.

(relative) ‘Peer to peer’ cyber-physical infrastructures have introduced in our societies new forms of networked sociality based on permissionless interactions between freely associating citizens, and these can happen on both the micro-level of a local territory, or city, but also at any scale up to the global. Peer to peer has led to the emergence of global open source and design communities that lie at the heart of new industries, such as free software and the shared designs of new electronics, including the self-management of mutualized urban resources. Citizens, private and public actors now have access to open collaborative ecosystems that are active at different scales. This means that peer to peer commoning is at the heart of the dynamic of the creation of many new urban commons.

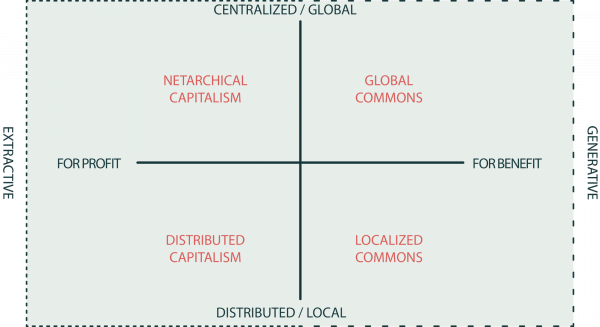

Defining urban commons is not always clearcut. Therefore some distinctions may be useful. See below the box in which we introduce a quadrant that allows us to distinguish very different types of shared resources, only some of which can be properly called urban commons. What is commonly known as the ‘sharing economy’, cannot always be called an urban commons! See our ‘four quadrant model’ in Box 2 below for an outline of these important distinctions.

|

Box 2: The four quadrant model of value-driven technological design While the vertical axis represents a polarity between centralized control of digital production infrastructure with global orientation (up) and distributed control with local orientation (down), the horizontal axis contrasts profit maximization motives (left) with a for-benefit or commons orientation (right). We call the left side extractive, because such political economies impoverish the natural and community resources they use through their value mode and mechanisms of capital accumulation. Here we distinguish netarchical and distributed capitalism, which differ in the modes of control of productive infrastructure, but both in essence represent the mixed model of ‘neo-feudal’ cognitive capitalism. We call the right side ‘for benefit’ or ‘generative’, as they aim to create common-good value at various scales, as well as add value to communities and commons, both social and environmental. Here we envision two scenarios: resilient communities and the global commons, or the hypothetical model of mature peer production under civic dominance. The aim of the commons transition, post-growth and other related ideas, in essence, is to shift from extractive to regenerative models and value modes. (Sources: Bauwens, Kostakis & Pazaitis 2019; Kostakis & Bauwens 2014) |

1.2 Cosmo-local production

The new dynamics of real urban commoning, which in a contemporary context involves the characteristic of being open collaborative systems, allow us to finally introduce an important concept, that of cosmo-local production.

The two dominant models for urban and territorial development are presently the neoliberal model, which is banking on local specialization in the context of the free flow of goods (and people) at a global level, but which has serious issues in terms of sustainability. It has recently been challenged once again with the spread of the Covid-19 viral disease, which has disrupted global supply chains. On the other hand, there is also a strong pressure towards all kinds of relocalization of the economy, on a continental, nation-state, or regional/local basis, but which may come at the cost of a closure of the economy, more virulent national competition, and sometimes, with xenophobic undertones or results. Cosmo-local production offers a potential third option. The underlying logic of this model is: ”what is light is global and shared, what is heavy is local’.

In sum, the cosmo-local model combines:

- An insertion of local productive models in the global networks for technical, scientific and experiential sharing, i.e. into the global open source and open design communities so that the local projects can benefit from the global advance of human knowledge

- An attempt at more ‘subsidiarity’ in material production, i.e. intelligent and appropriate relocalization of production closer to the places of human need

- A preference for microfactory models and governance/property models that have more local distributional effects, i.e. keeping a larger part of the value distribution at the regional level

A potential example is the emergence and growth of the Multifactory model (Salati & Focardi 2018), with 120 of such cooperative places for craft production on the European continent. The multifactory model represents a cooperation between craft and small producers who process materials, but also collectively manage a shared Invisible Factory that is the locus for their common knowledge and expertise, and which functions as their technical commons. According to research by Ezio Manzini, many such productive units are now emerging at the city level, characterized by being Small, Local, Open and Connected (SLOC) in orientation (Manzini & M’Rithaa 2016).

|

Box 3: The Multifactory Model Multifactories are self regulated shared working environments which “prove that the concepts at the base of free knowledge sharing and free access to resources can apply to physical places and spread into ‘common’ society, or people not involved in specific movements, or driven by a particular ethic purpose (Focardi & Salati 2016). They are not co-working spaces, fablabs nor makerspaces, but bring these and other concepts together for autonomous economical agents (freelancers, entrepreneurs, artists, etc.), which can, through the Multifactory, interact as if part of a company, with bottom up governance. In summary, they are (ibid.):

|

Table 1: Cosmo-Local Production. Source: Ramos (2017)

| Traditional manufacturing enterprise | Distributed manufacturing enterprise (neo-liberal global factory) | Cosmo-localization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IP / knowledge sharing regime | Held by one company | Held by one company or consortium (e.g. Apple) | Shared under open or CC or Peer Production licence etc. |

| Location of manufacturing | A single of local manufacturing center | Global factory, wherever the product can be most cheaply and effectively produced, elements of product can be produced | Globally distributed networks of localized manufacturing, depending on take up and use of global design commons |

| Transport and trade | Product sent from local manufacturing centers to other places | Parts move across many countries and once assembled are shipped for trade | Requires development of localized production ecosystems for complex manufacturing, Micro-manufacturing clusters |

| Enterprise model | Publicly Listed Corp., Family Owned Corp., Nationalized Corp.. | Corporation or consortium with complex supply and distribution ecosystem | Open value network model, Platform Cooperatives, Maker spaces, Phyles / Transnational collectives |

2. Advantages, Opportunities and Challenges of Commoning in an Urban Context

2.1 The main advantages of urban commons

There are a number of advantages to recognizing the vital role of the commons and commoning in the context of urban development and city-making. The first is that mutualization can play an important role in reducing the human footprint. For example, common transport, like public transport but also other forms of shared transport, such as associative and cooperative car-sharing arrangements, can substantially diminish the matter/energy footprint of human societies.[3] One recent study of associative car-sharing in San Francisco showed that every shared car replaced from 9 to 13 private cars (Shaheen, 2017). Of course many other complex factors are involved but tendential savings are certainly part of the impact of more commoning. As cities have to become more resilient in an age of potentially diminishing resources in a context of planetary overshoot, mutualizing and pooling provisioning systems are therefore an important part of the response.[4] Faced with market and state failure, citizen-groups are now engaged in retaking control of certain provisioning systems, such as the German village cooperatives that take care of renewable energy, or the multitude of collective purchasing groups that connect to organic farmers directly, or the copying of the US Community Land Trust model in Europe. Various studies document the rapid rise of such urban commoning. For example, the Oikos study shows a tenfold rise in urban commoning in just one decade after the crisis of 2008 (Noy & Holemans 2016).

The second advantage is to see the commons as a ‘school for democracy’, as commons are by definition managed by the communities themselves (and the norms and rules they collaboratively set) or through internally regulated multi-stakeholder and polycentric governance arrangements. Commons are a rare school of self-organization, which strengthens the democratic culture of a society, beyond the representative electoral paradigm. Our schools and factories, the places where we spent most of our lives, are likely not democratic, and voting is just not enough to co-determine our futures. Commons are therefore a missing ingredient. We will later discuss the emergent practices of contributory democracy when we look into the new institutional arrangements associated with the urban commons.

Even though commons are based on the free association of citizens, and can be associated with the dangers of affinity-based organizing, they can also contribute to the goals of greater inclusivity. Indeed, commons are not organized only by relatively more educated citizens. There exist numerous civic, religious and ethnic commons that compensate in areas where the market or the state do not provide sufficiently, especially to marginalised groups. Moreover, commons can be organized with the aim of achieving more inclusive social goals. Of relevance here is the work of French scholar Geneviève Perrin, who is studying a convergence between the works of Elinor Ostrom and Amartya Sen, and her concept of “commons of capabilities” (Perrin 2019). Our proposed “partner state” model which we discuss later, is based on the idea of an enabling, facilitating and participatory state form, which stimulates the capabilities of citizens to participate and contribute to the commons of their choice. In line with Foster and Iaione (2016: 288), this vision applies at the city level as well. In the latter case, the city as a whole is considered to be a commons, subject to poly-governance based decision-making. This does not necessarily mean bypassing the representative process, but rather the elected officials engaging in collaboration with other stakeholders and communities to co-govern certain city functions.

Finally, commons-based peer production as a new and emergent modality of economic production holds key advantages for the future of human labor. The logic of peer production as open collaborative systems follows that they are open to all contributors with the necessary skills, who can therefore follow first of all their passionate engagement. As Pekka Himanen described in The Hacker Ethic (2001), peer production combines freedom and passion, peer production combines both freedom and passion, in that commoners are free to choose the particular commons engagement that they are passionate about, and subsequently create economic ecosystems that make that engagement sustainable over the long run. Such self-directed activities are usually very motivational, and lead to a multitude of entrepreneurial efforts. With the proper incubation institutions, support for improving skills, and appropriate regulations to secure the risks undertaken by these new types of autonomous workers, this type of contributory labor can be at the heart of territorial development of a new economy around resilience and ecologically and socially regenerative activities.

Taken together, the commons can thus be seen as a new tool and priority in the transformation of our cities and polities toward more resilient models, as they can stimulate local and regional economic and social development. In this scenario, using commons-centric models, centered around the development of ‘third spaces’, helps integrate both physical, service-oriented and knowledge-oriented workers in integrated and open collaborative systems, which reconnect social groups that may be growing apart in the current urban logics of gentrification, outsourcing and hyper-specialization. Commons-based strategies can and should be a vital part of territorial and bioregional development policies that aim to stimulate more locally resilient economies.

We put forward an interesting prototype from the city of Ghent to illustrate this dynamic. The city needs to deliver five million meals per year in its public schools. An experimental program, under the lead of the nonprofit Wervel, showed that a combination of contracts with local organic farmers, a zero carbon transportation network of cargo bikes, and the re-hiring of cooks in these public schools, could guarantee 100% local, fair and organic food to all school children, integrating in one system all kinds of workers, both physical (food production and delivery) and cognitive (such as the geek labor in charge of maintaining the digital platform). Such largely self-governed ecosystems that integrate the service ‘proletariat’ with the cognitariat can play an important integrative role that restores the weakening public domain. Such potentials are coupled to equally important difficulties and path dependencies, as the commons system was for a long time an unrecognized part of society. Thus, in the next sections we delve deeper into how regenerating the commons poses a challenge to existing institutional arrangements.

|

Box 4: An example of public-commons partnerships: Energy cooperative Wolfhagen In the German city of Wolfhagen a joint enterprise energy company was created by the association of 264 citizens and the local authority in the form of a new cooperative – BEG Wolfhagen. After an initial period of limitation of membership to the founders of the cooperative, the cooperative opened up to membership of any citizen of Wolfhagen who purchases energy from the company, making it a consumer cooperative. This initiative is one of the few examples where a Common Association sits on the board of directors. The 264 citizens who created BEG Wolfhagen have launched an offer of cooperative shares. This raised € 1.47 million of the € 2.3 million needed to secure a 25% stake in the local energy company. Given the gap between the cooperative's capital value and the valuation of the 25% stake, the city gave the cooperative the opportunity to gradually capitalize its stake through a loan. This new capitalization period lasted around 12 months, with the cooperative fully covering its share of 2.3 million euros in spring 2013. At the end of 2016, BEG Wolfhagen had 814 members, or nearly 7% of the population of Wolfhagen, with a cooperative heritage of more than 3.9 million euros. Now, any new member of the cooperative has two years to pay their initial share in 20 installments, allowing access to the cooperative to be extended to low-income households (for more information, see Sultan 2020; Milburn & Russel 2019). |

2.2 The commons as a challenge for the market

Just like older forms of mutualisation, the new commons have their roots in civil society, however this new layer of citizens’ initiatives presents itself explicitly as such. These new types of citizen-activists reject both an evolution towards the semi-public domain (i.e. cooptation by the state), as well as towards market organisations (appropriation by extractive market forces), but also the exclusive professionalisation of the old civil society. The new urban commons are much more characterised by a culture of horizontality, free contribution (and, by extension, free ‘non-contribution’), and a drive towards individual and collective autonomy. The revival of the commons is first and foremost a challenge for the dominant view of citizens and society in the current societal model, and for the almost exclusive vision based on the division between market and state. The commons invite political and social movements as well as market and government players to evolve from a binary world view toward a triarchic world view, in which problems and solutions are seen as a specific kind of connection between market, government and commons.

The commons also pose a challenge for market players with a private profit motive. The commons dynamic creates a new kind of company, which is generative with respect to the commons and the citizens’ collectives. Contemporary commons-centric citizens’ initiatives often lead to the creation of new businesses, as commoners seek to create livelihoods to sustain their contributory activities. The commons therefore also imply an aspect of employment, in which the creation of work can be very significant.

The non-material commons, based on the sharing of knowledge, represent a special case, being at odds with the usual privatisation of knowledge through intellectual property. An essential problem here is the relationship between the regulations and the government’s cooperation with traditional private profit economy and its problems of ‘externalities’ on the one hand, and the common, often socio-ecologically oriented companies on the other. In terms of market forms, the commons stimulate new ‘generative’ market forms that pay more attention to integrating values such as sustainability, knowledge sharing, the mutualisation of infrastructure and a more inclusive distribution of economic value. Social entrepreneurship, impact investors, ethical investors, community currencies and crowdfunding are also potential means of supporting commons.

As Marjorie Kelly explains: “The generative economy is not a legal exercise but the embodiment of an emerging value system. Companies in the generative economy are built around values: the John Lewis Partnership’s core value is fairness, while Organic Valley’s core values are sustainability and community. Generative values become enduring through the social architecture of ownership. The generative economy is built on a foundation of stakeholder ownership designed to generate and preserve real wealth—resources held and shared by our communities and the ecosystems we live in. These enterprises don’t have absentee ownership shares trading in a casino economy, but ownership held in human hands.” (Kelly 2012a) Thus, instead of leadership and management coming from the government or the market, instead of public-private partnerships, we should look towards public-social partnership (i.e. public-commons partnerships) and public-social-private partnership models.

Table 2: How to define generative enterprise models by Marjorie Kelly

| EXTRACTIVE OWNERSHIP | GENERATIVE OWNERSHIP |

|---|---|

| 1. Financial Purpose: maximizing profits in the short term | 1. Living Purpose: creating the conditions for life over the long term |

| 2. Absentee Membership: ownership disconnected from the life of the enterprise | 2. Rooted Membership: ownership in human hands |

| 3. Governance by Markets: control by capital markets on autopilot | 3. Mission-Controlled Governance: control by those dedicated to social mission |

| 4. Casino Finance: capital as master | 4. Stakeholder Finance: capital as friend |

| 5. Commodity Networks: trading focused solely on price and profits | 5. Ethical Networks: collective support for ecological and social norms |

Source: Kelly (2012b)

2.3 The commons as a governmental challenge

For the government, and the political world that directs the government within a democratic system, the commons also represent an additional challenge since they constitute a new claim with regard to the exercise of power (ie. a normative claim to a resource and how it is governed; Foster & Iaione 2016). When a group of citizens claims or establishes a commons, with or without government permission or oversight, this is a claim that questions the traditional forms of representative democracy. Just as classical civil society – first as an expression of the workers’ movement, and later with regard to the broader social, cultural and identity problems following the 1960s – the commons are an invitation to further develop a ‘super-competent democracy’ or ‘democracy+’,[5] a new kind of mixture of representative and more direct forms of democracy (see Bauwens & Niaros 2017). The self-managing of commons through citizens’ collectives is an extension of democratic forms to new domains, including market functions previously managed on a purely private level. Relevant questions here for city officials, that the urban commons movement, initiatives and models address, would thus in sum be:

- Are there new institutional forms that can integrate these new claims into a reformed social, political and economic system?

- Can we move from a representative democracy with participation to more extensive forms that recognise the ‘right to initiate’ of civil society and its claims to create and reproduce self-managed commons?

- Can we really evolve into a ‘partner city’ that supports and guides these commons initiatives? What can such a transition look like?

The specific challenge for the government and the democratic system is to establish the right way of working together – including by means of new institutional channels and forms of exercising the rule of law – so as to connect the representative logic of the democracy ‘of all’ (and the deepening of this through participation and deliberation) with the specific ‘contributory’ logic of the commons and citizens’ initiatives. After all, the latter are not ‘representative’, but instead point to a new logic of ‘contributions’, while the management and decision-making mechanisms (governance) very often have that ‘contributory’ character. It is the contribution to a common project, in the co-production process, that provides the ‘voice’ here.

Finally, the commons also represent a challenge with respect to social inclusion and inequality between citizens. A new role of the government would be to become a meta-regulator of the commons, in such a way that the potential of every citizen and inhabitant can be stimulated. A purely invisible hand of self-constituting commons, potentially constituted by people already sharing prior affinities, such as for example, knowledge cultures, may pose certain problems in terms of social equity, justice and (dis-)empowerment. For example, citizens with higher income and more free time, could potentially have more time to participate in or establish commons, than citizens working two or more jobs merely to survive. In this context, the role of the city as meta-regulator is to guarantee the ‘commons capabilities’ of all its citizens, i.e. a ‘commons of capabilities’.

The need to adapt government practices to the commons also has an important legal aspect. After the French Revolution, the commons largely disappeared from the law books and from legislative thinking. Regulations evolve in the context of the social demands of powers of opposition (the workers’ movement up to the 1980s, for example), and over the last few decades have taken place in a context of deregulation. The self-management of actors seeking profit maximisation remains fundamentally problematic, however, and therefore a great deal of regulation is based on mistrust of the private individual in his capacity as a citizen and in relation to companies. But commoning practices, including the generative economy, are based on a fundamentally different attitude, namely that of the creation of shared goods and services in a context of general interest. As such, there is, in our opinion, a great need for innovation in modes of governance and regulation that can actively and reflexively support commoning activities. In conditions of neoliberalism, such frontrunning work must learn to leverage (and augment) both bottom-up and top-down approaches (Gough, 2017).

2.4 The commons as a challenge for civil society

The commons are also a clear challenge for traditional notions of civil society. The commons bring with them new forms of coordination and management, which are much more based on informal contributions, voluntary action and much more horizontal management practices, which are also critical with respect to exclusive forms of professionalisation and ‘managerialism’, without rejecting them outright. The majority of citizens’ collectives do not count themselves as part of (traditional) civil society, but we can also see that civic society organisations, old and new, do indeed play a facilitating, supportive and infrastructural role. Just as we can observe the need for a more supportive and facilitative government, we can also observe the need for a more supportive and facilitative civil society. The important thing to observe is that digital networks can constitute semi-formal ‘organized networks’ that differ in significant respects from the traditional non-governmental organizational model, and that NGOs are adapting to the new realities by potentially becoming more facilitative organizations. This new type of institution, also goes by the name of for-benefit associations or ‘community management organizations’.[6]

3. Institutional Adaptations to the Reality of the Commons: From a Binary to a Triarchic World?

3.1 A new political and economic structural framework around generativity: first lessons from Bologna and Ghent

During 2017, one of the authors of this chapter and other colleagues of the P2P Foundation research network were commissioned by the city of Ghent in Belgium to map the urban commons, conduct conversations with founders of pioneering projects, and advise city authorities on adaptations of the city towards the commons-centric citizen initiatives. Here were some of our findings.

|

Box 5: The Commons Transition Plan for the City of Ghent “For the City of Ghent, the central question of this research and participation project was: how can a city respond to this and what are the implications of this for city policy? The goal was to come up with a synthesised Commons Transition Plan that describes the possibilities for optimal public interventions while also offering answers to the question of what Ghent’s many commoners and commons projects expect from the city.The intention of this assignment is therefore to investigate the possibility of a potentially new political, facilitative and regulatory relationship between the local government of Ghent and its citizens so as to facilitate the further development of the commons.” For more information, see Bauwens & Onzia (2017) and Bauwens & Niaros (2017). |

Figure 2: Synthetic overview of the urban contributive economy. Source: Bauwens & Onzia (2017)

Figure 2 shows the underlying ‘value logic’ of urban commons, which in Ghent grew from 50 to 500 projects in ten years.[7] These urban commons are most often grassroots efforts that create open contribution-based communities, i.e. they are not market, state or even NGO models . As commoners try to create livelihoods around their contributions, in order to maintain the existence of their projects over the longer term, they frequently create some type of economic activity around these efforts. Many of these efforts are also supported by ‘for-benefit associations’ that maintain the infrastructure of cooperation without commandeering the efforts of the commoners. They are non-profits but function as facilitating and mediating institutions

The common use value of these projects is first of all created through contributions, but subsequently or concurrently, efforts are made to create a generative economic sector around these activities, and a new type of not-for-profit institutions, which we call for-benefit organizations, that enables these projects. We define them as common good institutions for the commons-based project, as they ‘enable the autonomous creation of value by individuals and groups’.

Another finding has been that even without formal policy from the city, public agents and other forms of support were present during all phases of these new projects, such as support for infrastructural organization, incubation and functioning of commons projects, and incubation of economic projects and support for the commons-centric economic activities. Therefore, city authorities must first of all recognize that they are already involved in supporting urban commons, but may want to develop a more coherent support of what is also a newly emergent value regime, one that is based on contributions, and not on either pure market activities nor as planned public projects. These projects advance the sustainable wellbeing of the urban populations, but may not always be directly measurable by GDP, to the degree to which they do not involve the monetisation of some or all of these activities. This highlights the importance of introducing new types of metrics (such as sustainable wellbeing indicators and ‘gl-urban’ doughnut economics) as well as redefinitions of work (e.g. to recognize and include socially and ecologically regenerative activities).

Nevertheless, healthy commons have historically, and today, also stimulated thriving marketplaces.

Referring back to Figure 2, note other characteristics of this model: the governance is often polycentric, combining public, social-civic, and economic institutions and organizations, combining nonprofit (no profit allowed), not-for-profit (profit must be re-invested in the social goal), and even for-profit models, which can consist of networks of freelancers, small and big companies, or entities from the ethical, impact, cooperative and solidarity economy. At the bottom, we place the Partner City model, where the city acts as a meta-regulator of the whole system.

Figure 3 shows the new logic of cooperation that may emerge, once the existence of the commons, and of the public-commons relationships, are recognized. This takes the form of public-commons cooperation protocols. The first more sophisticated form of such cooperation probably originated in Italian cities, more precisely in the city of Bologna. The Bologna Regulation for the Care and Regeneration of the Urban Commons is based on a specific model that has been emulated in more than 250 other Italian cities and it has by informed accounts mobilized around one million Italian citizens to take care of their urban commons.[8]

Figure 3: Public-commons cooperation protocols. Source: Bauwens & Onzia (2017)

A marker of this movement is a recognition of a right of initiative of the citizens, who can claim a commons, a right to care. Many of these cities then initiate a ‘Commons City Lab’. an institution where citizen-commoners can seek validation and legitimation for their projects. This is then formalized through a ‘Commons Accord’, a mutual agreement between the citizen groups and the city, which specifies mutual duties of support. The city hereby functions as a convener of the support coalition, sometimes following the Quintuple Helix model (Foster & Iaione, 2016). In this model, the city is accompanied by 1) the Chamber of Commerce or similar entrepreneurial forces 2) the knowledge institutions (universities, etc..) and 3) the official civic organisations (NGO’s), who together, examine the conditions of support for the fifth partner, i.e. the commons projects themselves. This model originates in the very similar model for the support of social innovation in general.

This model also has very strong economic implications, in the context of a potential new ‘value regime’ that integrates the presently excluded ‘externalities’. First of all, in this model, what is primary is not the commodity value of goods/services or labor power, but ‘contributions’, as defined and experienced by that particular community. Commodity prices and income may be involved, but they exist in hybrid arrangements around the core contributory logic of the specific community. As we found in a study of 300 peer production communities (P2P Value), nearly three-quarters of them were involved in or have experimented with contributory accounting. This usually involves creating a membrane distinguishing the inner logic of the community from the outer logic of the existing market or governmental forms (prices and subsidies). This is similar to the description in Bernard Lietaer’s study of pre-capitalist monetary forms in The Mystery of Money (2000), which combined the external ‘cold currencies’, with internal ‘warm currencies’, whereby the latter determine a different distribution of value, (sometimes called predistribution) since the new value requirements are established a priori by the community). In other words, the project may seek classic funding from external sources, but combine this with innovative forms of internal value definition distribution.

Second, these commons projects may seek the type of income and funding that maximizes their freedom of action and value regime. This is why we speak of an ‘ethical economy’ or a generative economy surrounding their projects. This may take the form of an entrepreneurial coalition which has specific usage and reciprocity arrangements with the peer production communities.

Finally, we recall the existence of the mediating facilitative organizations. In Figure 4, we stress the new potential logic of ‘contributory democracies’. The figure shows the institutional arrangement that the city created to facilitate the food transition efforts in line with climate objectives, with some of the extra proposals that were forwarded to the city administration.

Figure 4: An example of contributory democracy: the food transition council in Ghent, Belgium (Source: Bauwens & Niaros 2017).

In short, neither a pure representative model, nor even a supplementary participatory model was sufficient to carry forward this dynamic. Representatives are highly sensitive to their sources of funding and financial support, while participatory models are often top down models that seek the opinion of citizens, but cannot source their already existing transformative practices. A merely representational model based on existing civil society dynamics, may invite in the council actors whose main goal is actually to slow down the required transformative actions This, then, is what contributory democracy brings to the table; a necessary counterweight of already transformative agents. In the case of the city food council ‘Ghent en Garde’, it managed to not only integrate citizen participation, but invited in the civic actors who were already successfully carrying out the transformative activities that the city needed. In other words, the legitimacy comes from citizens already expressing in practice, the legitimate political goals of the representative regime. This is indicated, in Flemish, as ‘Working Group on City Agriculture’ which represented these new actors.

One of the primary other examples comes from Barcelona, where the city has initiated a so-called communitarian management framework called Patrimoni Ciutadà. This regulation enables citizens and neighbors to manage citizen heritage projects, mostly referring to old urban voids and important historical buildings. A similar participatory framework has been voted on by the Lisbon City Council in 2010 in order to promote neighborhood preservation and improvement, which benefits seventy-seven Priority Intervention Neighborhoods and Zones. These and other examples are collated in the European policy brief prepared by Generative European Commons Living Lab (2020). There have been quite a few more examples of such public-commons cooperation protocols which we have summarized in an overview in the Appendix.

Figure 4 above also refers to Assemblies and Chambers of the Commons. These are not public-commons institutions but proposed autonomous institutions of the Commons. The Assemblies of the Commons federates citizens that are actively engaged in the creation and protection of urban commons in a particular city or region, while the Chambers of the Commons is a proposal for creating links with the generative enterprises that work with commoners and commons. An Assembly of the Commons was pioneered by Lille in northern France and has been informally operating for several years and is being emulated under various names (such as Fabrique des Communs, etc.). The city of Grenoble has been supporting a permanent assembly of this type. One of the outcomes of this work has been the presentation of public policy proposals to candidates in the municipal elections of France in May 2020. The ‘documentary’ initiative Remix the Commons has compiled a "Politiques des Commun: Cahier de propositions en contexte municipal”,[9] which is an overview of commons-oriented policies proposed for the municipal level.

3.2 Moving from urban commons to the city of the commons

Foster and Iaione take the conception of urban commons further by arguing that a city itself may be considered as a commons, as“from the descriptive framing of the commons, the city is an open access good subject to the same types of rivalry, or contestation, and congestion that needs to be managed to avoid the kinds of problems or tragedies that beset any other commons.” (Foster & Iaione, 2016: 288). Such an approach to the city itself as a commons echoes deeply with evocations of the right to the city, which David Harvey (2008) describes as a common, rather than an individual right to change ourselves by changing the city, as this transformation depends on the exercise of a collective power. Based on the city as a commons approach, Foster and Iaione have outlined a new institutional model, namely, commons-based urban governance.mThey base the model on three design principles: horizontal subsidiarity, collaboration, and polycentrism (2016: 326–334). Below we zoom in on the articulation of polycentricity in the urban context. According to Iaione (2016: 433–434) applications of the principles of polycentric governance includes:

- Everyday commoning, or the enabling of collaborative and commining behaviours, habits, and urban civic duties)

- Wiki-commoning, or collaborative and public communication, and creation of local net-works in forms such as

- maps of urban commons and commoners;

- platforms for sharing initiatives aimed at taking care of urban commons, and;

- systems that involve citizens in monitoring and protecting the urban commons

- Collaborative urban planning and policy making, or public, private, and civic collaboration as a strategic innovation in urban development

Sheila Foster and Christian Iaione (2017) have further distilled five key design principles for the urban commons:

- Principle 1: Collective governance refers to the presence of a multi-stakeholder governance scheme whereby the community emerges as an actor and partners up with at least three different urban actors

- Principle 2: Enabling State expresses the role of the State in facilitating the creation of urban commons and supporting collective action arrangements for the management and sustainability of the urban commons.

- Principle 3: Social and Economic Pooling refers to the presence of different forms of resource pooling and cooperation between five possible actors in the urban environment

- Principle 4: Experimentalism is the presence of an adaptive and iterative approach to designing the legal processes and institutions that govern urban commons.

- Principle 5: Tech Justice highlights access to technology, the presence of digital infrastructure, and open data protocols as an enabling driver of collaboration and the creation of urban commons."

3.3 At the societal level: from a binary governance model to a triarchic model

While in the previous sections we discussed the microfoundation of the commons-centric value regime, in this section we make a somewhat more hypothetical leap towards a possible post-capitalist social-institutional model that is inspired by the seed forms just discussed. What if this emerging seed form was the prefiguration of a potential reshuffle and transformation of the three basic human institutions? It is here that we draw on the work of Kojin Karatani, who has described the current political economy as a three-in-one, i.e. Capital-State-Nation:

- Capital accumulation drives our wealth creation and is our value regime, based on a combination of the core commodity system, augmented by the appropriation of what Jason Moore called ‘cheap natures’, which have fed accumulation in its different historical phases, but has reached a stage of exhaustion due to the increasing overuse of resources

- The state is the meta-regular of our society, but centers around servicing the needs of the market, because of the basic conviction that growth is necessary to finance everything else

- The nation is the historically constituted community that co-emerges with the two other forms

Within this logic, Karl Polanyi has seen a double movement at work, sometimes called the lib-lab movement, a succession of waves of development, in which the market frees itself of societal constraints during the ascending phase, which creates unequal growth which in turn results in a deregulated society. This then prompts the ‘nation’, i.e. ‘the people’ to revolt, forcing the state to re-regulate the market. Polanyi’s changes are changes within the existing institutional paradigm, whereas Karatani, in his The Structure of World History (2014), shows the historical succession of different societal paradigms, according to their mode of exchange, i.e. the primary allocation method. Our argument follows the potential pathways of both Polany and Karatani, i.e. a reformational versus a more fundamentally transformational pathway. We believe both that a new subsystem is emerging which exhibits a number of different characteristics from those of the earlier paradigm, as well as that this may lead to a ‘new normal’, in which the institutional relationships are challenged and reshuffled more deeply, resulting in a new institutional paradigm. To be clear: urban commons and their peer-to-peer dynamics may be seen as

- the emergence of a new sector in society, that the existing institutional order adapts to, and integrates;

- a deeper reform movement within the present political economy;

- a fundamental transition to a new civilizational model.

However, in any of these cases, our argument suggests a transformation of the inter-relationship of these three human institutions, based on the logic of contribution:

- At the core of this new value regime is an active value-creating civil society, which actively participates in commoning, and cares for the shared resources that it needs for the good life

- Around this core civil society exists an ethical and generative market system, which creates livelihoods for the citizens, but acts in a generative capacity towards the human communities and the web of life in which they are embedded

- Finally, facilitative common good institutions, the res publica acting as the ‘commons of the commons’ defend the integrity of the whole system in a ‘partner state’ configuration which augments the capability of its citizens to participate fully in the creation of common value

Figure 5: The relation between state, economy and civil society under a P2P model. Source: Kostakis & Bauwens 2014)

3.4 The new institutional framework of the Partner City: public-commons cooperation and the commonification of public services

The emergence of a commons-centric ecosystem necessitates a specific interface between the public sector and the new civic sector. They take the form of public-commons partnerships, or, potentially, public-commons-private partnerships (Fattori 2012; Milburn & Russel 2019). The impetus for such an institutional interface arises in a context where neither the state nor existing market dynamics are seen to be up to the task of solving specific salient societal issues, or when both mono-logical private or state-based organizational forms may be rejected, and where a new interface of cooperation between the public sector (or public-private sector), and the commons-centric civic collectives, are seen as a necessity. Other factors include the presence of alternative economy narratives, often emerging as counter-narratives in the context of often devastating effects of urban (extractive, Silicon Valley inspired) sharing economy developments like Uber and Airbnb, depending on local regulations, but may also arise from particular local practices, traditions and cultures.

At scale, it takes the form of a hybrid property and/or governance arrangements, but it can also take the form of concrete ‘commons accords’. The primary aim is to reinforce the capacity for autonomy of commons-centric projects, and to provide them with capitalisation capabilities. Ideally, it strengthens the autonomy of the projects, while the alliance with public actors injects the elements of the wider common good that individual projects cannot necessarily carry on their own. In terms of governance, they often combine a public authority agent, joined by a commons or civic association which represents the commoners. This means three actors are conjointly at work: the public authority, the jointly governed company as such, and the autonomous civic association. The surplus that is generated is primarily governed by the joint company, but if the ecosystem becomes healthy, it can also fund the civic association’s enabling of participatory projects. The funds are used to strengthen the ecosystem but also to expand the model to new domains. Property can also be put in an inalienable trust, to avoid later sale by state actors to the private sector.[10]

3.5 The New Frontier: Urban Data Commons

“By helping citizens regain control of their data, we aspire to generate public value rather than private profit. Our goal is to create data commons from data produced by people, sensors and devices. [...] We envision data as public infrastructure alongside roads, electricity, water and clean air. However, we are not building a new Panopticon. Citizens will set the anonymity level, so that they can’t be identified without explicit consent. And they will keep control and ownership over data once they share it for the common good. This common data infrastructure will remain open to local companies, co-ops and social organizations that can build data-driven services and create long-term public value.” Francesca Bria, member of The Decode project. Source: Bria (2018)

The new frontier for urban commons is undoubtedly collective management of public-commons data. Data do not merely consist of information about individuals, but are relevant for cities because they are about dynamic relationships between people, places, things, and much more. Data are essentially relational, therefore it is not sufficient nor desirable for them to operate under privacy protection and individual ownership models. In the neoliberal ‘smart city’, save for a few pioneering commons initiatives, data are either enclosed and controlled by private players, also excluding public authorities, or are managed by city or other public institutions alone. Data are eminently suited for collective multi-stakeholder governance, decision-making and ownership, as they are essential tools for the assessment and transition management of complex city functions and metabolisms. Such data are most suited for commons forms of ownership, so the right to the urban data commons (Iaione, De Nictolis & Suman 2019; de Lange 2019) is a crucial frontier.

Building data commons for cities means developing new standards that enable collective rights to data. In a recent paper, Iaione (2019) outlines four dimensions of technological justice for the smart ‘city as a commons’, summarized in Table 3 below:

Table 3: Four dimensions of technological justice for the smart ‘city as a commons’ (Source: Iaione, 2019)

| Access | Citizens and marginalized groups must have equal access to the means of cooperation. Addressing the digital divide, in terms of access to devices, but also digitized public services, is a key factor in bringing together a diversity of people to self-organize for the set-up and governance of urban commons |

|---|---|

| Participation | Promoting self-organization of urban communities is key for fostering citizen participation in projects and initiatives related to the production, decision-making and management of digital infrastructures and services (e.g. e-government, open data and citizen sensing initiatives) |

| Co-management | This dimension focuses on the presence of defined roles and responsibilities for civic actors and communities envisaged by the project promoting the involvement of the city inhabitants in the direct (including, but not limited to professional) management of digital infrastructures or services. |

| Co-ownership | The final test: Are the communities involved, as a result of access to technology and the overcoming of the digital divide, able to collectively participate in and build their own cooperative platforms, or even configure a system of ‘civic digital enterprises’, distributed in the city? |

One of the most prominent pioneering examples of managing data as commons is Barcelona, which has embraced a ‘smart citizen’ approach since 2011. Flagship initiatives include Poblenou Maker District (formerly FabCity) and project DECODE, as well as their and other numerous continuities, e.g. Sentilo, CityOS and Bicing, corresponding to challenges of digital transformation, innovation and empowerment in the direction of citizens’ technological sovereignty (Ribera-Fumaz 2019). Other recent examples include ‘Civic eState’ and co-city experiments in the Italian cities of Naples and Turin.

|

Box 6: Urbans Commons in the Global South: are they different? In 2017, P2P Foundation researchers participated in a major review of urban commons, led by the Laboratory for the Governance of the City as a Commons (Iaione, Foster & Bauwens, 2017), one of the major consultancies on public-commons cooperation, and which, together with LabSus, co-produced the Bologna Regulation and has been very active in promoting the Co-Cities approach. A review of the first hundred cases (out of 1,000) led to a surprising conclusion. In the Global North, most urban commons are in practice not just tolerated by public authorities, but most often assisted, informally or formally, as our discussion above has shown, culminating in a call for formal public-commons cooperation protocols. However, this is not the case in the urban commons studied in the Global South. In fact, it would seem that many local, regional and national authorities are very much under the influence of growth-driven developmental models, which see the commons as a hindrance. In having to actively defend themselves against encroachment by public authorities, urban commons in the Global South have to be more autonomous and sturdy. One of the first conclusions from the case studies is that cooperation with governmental institutions, especially at the national level, but not exclusively, and thus any practical instantiation of polygovernance that include official entities, is problematic for nearly all projects, with few exceptions. In the case of the Bergrivier project, aiming to stimulate local economic streams using a complementary credit-commons based currency, there is a clear distrust and rejection of the more central authorities, seen as corrupt and neoliberal in their orientation, though this project is exceptional in that it found active and benevolent support from city officials. Project leader and author of the case study Will Ruddick also stresses that however difficult at the institutional level, there are always ‘interstitial’ individuals, who can make a difference and create some level of cooperation even within indifferent and hostile governmental entities. The Ker Thiosane project leaders in Dakar specifically mention the indifference of authorities, even as the success of the project to revitalize a poor neighborhood is obvious. At issue here is the inability or unwillingness of governmental personnel to ‘see’ and understand the logic of commoning, especially when it is ‘extra-institutional’ i.e. happening outside the sphere of both government, business, as well as ‘classic’ NGO’s. The Platohedro contributors of the cultural project in Medellin, Colombia say that they see the city and regional governments as opportunistic towards urban commoning, and therefore cannot be counted on. Other projects themselves reject governmental interference or even support. For example, the Hacklab project in Cochabamba tries to maintain smooth and non-partisan relations with the local government, but keeps them at a distance in the context of maintaining the autonomy of the project. The MInha Sampa campaign organization in Sao Paulo, Brazil, similarly actively rejects government funding because their citizen-led campaigns are most often based on demands directed at the government. The Woelab project in Lome, Togo, actively rejects the mentality of seeking help from donors, which is seen as a form of post-colonialism that disempowers personal and collective autonomy. The organizer states that “There is no support neither from the government nor from the city and the project is entirely marginal” (LabGov.City 2019: 24). On the other side of the polarity is the Karura Forest project near Nairobi, Kenya, which stresses the necessary role of the government as framer of the local cooperation, i.e. the Forest Act of 2005 frames multi-stakeholder governance; the City-based Forest Conservation Program, the county’s environmental portfolio and the Kenyan Forest Service all have a stake. Even more positive are the experiences of the Manzigira Institute, which works on the welfare of urban farmers, and claims a good response from the local governments in listening and considering its policy recommendations. |

4. Potential Facilitating Actions

4.1 What can public authorities do to support commoning

It cannot be said that the commons are re-emerging in a supportive environment. On the contrary.

First of all, after the UK Enclosure Acts, the anti-commons regulations of the “bourgeois revolutions”, and especially after the Napoleonic legal reforms in continental Europe, the commons disappeared from civic consciousness, (except for the mutualization of life risk undertaken by the labor movement in the 19th cy.) and were often seen by the social elites as an unproductive remainder of a feudal past. The legal framework became mostly a public-private affair. All this is reflected in the legal codes of countries that became growth-oriented market societies. Public policies favour economic growth and the market, and non-monetary commons are often seen as a hindrance, including by the pro-redistribution left, which most often chose for state-centric priorities. When we researched the urban commons in Ghent, we received a 7-page memo from the commons land trust, habitat cooperatives and coworking groups outlining the long list of legislation that negatively affected the commons, while legal groups like the SELC in San Francisco[11] are very much focused on changing legislation and regulation that hinders the commons. One live but virtual conversation with the founder of the SELC Janelle Orsi,[12] struck me: “Do you know that it is forbidden to collect rainwater, that is forbidden to dry your clothes in the sun, to make marmalade and share it with your neighbors, to grow vegetables in front of your house.” This summation of local county regulations in California is rather illustrative of the countless hindrances that sharing and commoning face in a market-centric legal tradition. It is also related to how a “market state”[13] sees the world it is operating in. In a world of competing private entities, whose ethics are primarily driven by working within the legal order but to achieve private ends, regulation is very necessary since it is based on the distrust of the ‘selfish’ motives of the main actors. But the same distrust, applied to generative commons-centric citizen initiatives, can be very counterproductive.

An important step for any public authority is therefore the simple recognition of the commons as a real and important wealth-building practice that is vital for glocal resilience and flourishing. Mapping the commons, such as efforts in Ghent, Amsterdam and elsewhere, is therefore a very useful and intuitive first step (Labaeye 2017). Public authorities wishing to take active steps towards supporting commons-oriented initiatives typically rely on a mix of outside expertise and aspirations toward institutional innovation, learning and capacity development, relegating specific mapping, action research and policy deliberation activities to purpose-driven task forces. Here it is also important to recognize collaborative mapping of potential local seeds of commons-oriented and otherwise alternative economies as a form of “wiki-commoning” (Iaione 2016: 433), that is, a particular mode of co-producing transformative knowledge (Labaeye 2017), while projects such as TransforMap,[14] Seeds of Good Anthropocenes[15] and Atlas of Utopias[16] show examples of how such maps can be collated at global scale as tools for translocal diffusion, sharing and mutual learning (Loorbach et al. 2020) for urban socio-economic re-design.

The important next step is therefore also to have specific regulatory frameworks that not only do not discriminate against commons, but even favours and support them as a key strategy to support sustainable wellbeing and diminishing the human footprint. Removing commons-negative regulations is as important as the building of commons-positive frameworks such as the public-commons cooperation protocols we mentioned above. Here we are specifically thinking of legal teams within city authorities that are specifically tasked with removing barriers to these initiatives while thinking through more positive frameworks, such as the Quintuple Helix forms of support mentioned above in the context of Bologna and similar positively enabling public-commons frameworks. Initial mapping activities discussed above may in this context be complemented by creating wiki-commons concerning local-specific policies as well as overarching systemic-level hindrances (as well as opportunities) in the development of commons-oriented initiatives in their role as providers, or prefigurations, of collective-based organizational modes for sustainable wellbeing.

The commons should be specifically recognized as a real and legitimate human institution that finds its place in the public planning processes of cities and regions. Recognizing and promoting the commons-friendly forms of property, such as the Community Land Trust (CLT) model, is a long term protective measure against both private and state appropriation. For example, combining CLTs (the land), with housing coops (the bricks), and co-housing (collective services) is a good defense mechanism against gentrification pressures. While city and state can sell public properties, this is a lot more difficult if the resources are protected as commons, and therefore designed to be inalienable, even from the state. This legal recognition can be further embedded in public-commons regulations. Transition councils, which have shown to be effective in transforming provisioning systems such as in food, can integrate commons-based contributive dynamics, as shown in the Food Transition Council of the City of Ghent. This is what has been called above ‘contributive democracy’. See Box 7 for five different institutional solutions that have been promoted in France, and which allow regional coalitions to be funded for eco-social transitions that frequently involve the creation of commons-centric projects.

|

Box 7: Poly-governed Regional Transition Modalities in France

|

Funding is a very important next step. In the Bologna model, once the project has been recognized, the city act as the coordinator of the support mechanism, through the Quintuple Helix model: the four ‘establishment’ stakeholders, i.e. the city, the chamber of commerce, research institutions and formal NGO’s, band together to discuss how to best support the projects. In the US, there is an important campaign to re-introduce public banking, which saved North-Dakota after 2008. In this model, public income is vested in a public bank,[17] multi-stakeholder governed and which can fund commons-centric projects at the local[18] or regional level. The French ‘Banque des Territoires’ (the public bank that funds regional development) is engaged in a project to fund the ‘third places’ (makerspaces, fablabs, coworking places) as agents in territorial transformations.

Social procurement, which adds ecological and fairness criteria to public procurement, and is legal even according to WTO rules, coupled with smaller grants that make the project uninteresting for large multinationals, can be effectively used for more local funding, as also exemplified in the Cleveland/Preston models, where the collective purchasing power of the anchor institutions is mobilized for local development. The ‘call for commons’ used in Ghent for temporary usage of unused land or buildings, can direct funding to the most collaborative projects.

More fundamentally, impact accounting models, like the 17-cluster assessment of the Economy for the Common Good,[19] can be used for judging local investment policies, favouring those projects that have the higher positive impact in terms of human footprint reduction, social equity and job creation.

Figure 6 outlines a model centered around what we call protocol cooperatives. If a city engages in the mutualization of its provisioning systems, which may be based on collaborative platforms as practiced by the platform cooperativism movement, it can join a league of interconnected cities, forming a translocal or trans-national for-benefit association that promotes and manages a global open design depository, where the necessary infrastructural software is available, with support of alternative ethical financing. This is the cyber-physical infrastructure that enables the mutual learning in mutualized provisioning systems, such as shared habitat, shared mobility, etc.. In this case, global knowledge commons are leveraged to provide a common core of cyber-infrastructure software, that can be adapted for local usage. Instead of just negatively regulating predatory gig economy players, cities can create positive momentum for generative solutions.

Figure 6: A trans-local cyber-physical infrastructure for mutualizing urban provisioning systems. Source: Bauwens & Niaros (2017)

Finally, we would stress the need for cultural change towards collaborative skills and practice, with concrete learning support for proto- or pioneering commoners. This is less related to any from of business incubation, but rather about transformative cultural learning, which enables ‘prosocial’ cooperation at the city level. An example of this was the Comunificadora[44] learning process in Barcelona, a training program specifically aimed at new or existing projects that need support to function in a transition to a social and solidarity economy based on the commons.

Throughout the commons transition planning process, it is also relevant to stress the importance of, but general underutilization of, participatory futures methods and tools that allow for the inclusive civic questioning of ‘used futures’ and generating collective insights, intelligences, designs and (pre-)experiences related to desirable urban futures and transition pathways. Such undertakings may involve taking as inspiration a combination of mapped local and global seed forms (Bennett et al., 2016), as well as proposed transitional policies and locally-contextual innovative institutional designs. This may combine more traditional foresight methods such as bottom-up visioning, backcasting and scenario planning, but may also utilize newer, more experimental, generative and experience-based approaches such as games and online foresight platforms,[20] prefiguring practices of anticipatory democracy (Ramos, 2014) and peer-producing futures (Ramos, Mansfield and Priday 2012). The concept of foresight commons as a type of knowledge and design commons goes against more established institutional foresight and futures practices at city, national or international levels, both in its strive toward radical inclusivity and an open-source ethos, as well as in its subscription to the commons and commoning as normative claim. As such, such tools must also, by their design and practical implementation, be able to confront potentially significant power gaps, as well as uncertainties, discomforts and knowledge gaps (Vervoort et al. 2015) associated with instituting local or larger scale mechanisms for the support of radically alternative socio-economic paradigms.

4.2 Promoting a Generative Economy

Already in 2011, based on figures from 2009, a U.S. report calculated that the ‘Fair Use’ economy,[21] i.e. that part of the economy that relies on shared knowledge instead of private copyright, represented one sixth of the American economy and had better withstood the negative effects of the meltdown of 2008. These calculations did not include the very strong growth of what is now called the ‘sharing economy’, nor the tenfold growth of the number of urban commons. This confirms that attention to the commons in the city is not a marginal issue, but a vital part already of modern economies, and as the open source software economy shows, they are a crucial part of the digital economy. Big data, or their alternative, data commons or data cooperatives, will further increase this importance.

For ‘classic’ entrepreneurs that want to rely on private or venture capital, there is a consistent ecosystem of private and public incubators where they can find assistance and guidance to find capital investments. Some of the more established alternative business formats, such as the cooperative economy and social entrepreneurship, may have more limited support ecosystems. But what is missing is a systemic promotion of generative entrepreneurship that can be linked to commons-centric production models. This lack of means leads to digital commons to be generally captured by large private enterprises which may not work generatively with the commons and commoners, or to be permanently underfunded as urban commons initiatives. But even alternative incubators may not be that ‘commons-friendly’. For example, even an ethical bank may ask for collateral that makes an open source commons impossible and many incubators do indeed insist on this. Even cooperative or solidarity economy based incubators may not take into account the specifics of the urban commons. One of our strong recommendations is therefore the creation of commons-centric incubators that pay attention to the generation of ethical livelihoods for the participants in commons-centric projects; the issue here is that for those commoners that wish to obtain a certain independence by generating their own revenues, or by creating a ecosystem with “generative entrepreneurs”, assistance and guidance is provided.

However, there has been the important innovation of Platform Cooperativism. In this format, the supply and demand for certain products and services will still find itself through online platforms, but the ownership of the platform will be worker-based, cooperative, or in a multi-stakeholder governance format. The Platform Cooperative Consortium has organized several conferences of this growing movement, which has even garnered support from labor unions in the anglo-saxon countries, which are creating union-cooperative based platforms, for example for domestic workers in the city of New York. Given the dominance of the economy by large global firms that control such networked platforms for communication and exchange (e.g. Uber, AirBnB, Google, Facebook) and that these practices come with huge negative externalities for cities, it is important to support and strengthen platform cooperatives that can be locally owned, forming a new type of urban commons that benefits the local economy.

This may be the time to experiment with radical new solutions as well. The ReGen network, for example, is prototyping funding mechanisms that can be directly applied to the generative work undertaken by commoners. These types of models rely on shared and distributed ledgers, which allow for the public verification of outcomes, for example decarbonization; the results, e.g. proven decarbonization by every citizen and citizen-group, would result in tokens that can be purchased, and therefore funded, by both public institutions and taxation, if the issue is recognized as a public priority, and by companies that recognize, or have to recognize, the positive social and ecological externalities that they are benefitting from. The French Community Land Trust, Terre des Liens, has calculated the huge positive externalities produced by organic farmers, which could be recognized if such protocols were adopted.

In general, an expansion of the value regime that recognizes such contributions could liberate many activities that fund and sustain ‘sustainable wellbeing’.

4.3 Promoting a commons-productive civil society

This last section is written with the commoners themselves in mind. What kind of strategies and tactics could commons-centric citizens envisage, to promote a thriving set of common resources? The authors believe that the ‘commoner’ is indeed a potential new political subject. A commoner is any citizen and inhabitant of a region or city that participates in the creation and maintenance of commons in the local area. A commoner is not merely a citizen who is interested in the political life of the city, nor a representative of the world of ‘labor’, which implies a relation with an employer within the commodity-system. A commoner is very specifically active around the creation of new institutions that define a new societal and civilizational logic and is active in a new emerging value regime. In short, a commoner has a vested interest in the creation of measures and institutions that defend and advance commons-based institutions.