About Money

= Summary written by MauroB in 2009

See also: Money

Introduction

MauroB:

When discussing free and open source software or free culture, one question always pops up: How do people make money from this? It surely can't be done professionally, in the sense that people can make a living from it?! The answer for software developers is that often customization for your client is a central part of your work and that you can build services like support around your software, or get paid by a big company like Google or IBM that heavily relies on free software. And obviously one can accept donations which works also for artists. They can also raise funds from charities or ask the state or museums to support their projects. Even today, most artists, writers, musicians or filmmakers can't make a living on their passion, in part because much money is already spent on the distribution (music labels or movie studios). Interesting examples of art are the Creative Commons licensed comic Scott McCloud did for Google to present Google Chrome or the very personal Four Eyed Monsters movie and video blog of Susan Buice and Arin Crumley who even put their feature length movie on YouTube. But one keeps wondering if there wouldn't be better ways which would enable even more people to make a living from free software and free culture.

Micropayments

One thing that has been proposed for a long time, but has failed to realize as of yet are micropayments. The idea is to make it very easy and cheap to transact very small amounts of money over the internet. When somebody likes a song or a piece of software she can just hit a button on the website and the creator gets his one or two dollars. Such a simple interface and no transaction costs would make tiny donations like that a lot more attractive and hopefully they would add up to a larger pile of money.

But maybe we need to change something more fundamental. Maybe, as we go from the industrialized information economy to the networked information economy, we do not only need to rethink the rules of intellectual property, but also the rules of money and the economy. Think of all the flaws of the current system (as evidenced by the ongoing financial crisis). The current monetary system works rather against free software/free culture and the spirit of sharing and community. But they still thrive, because humans will always care about such things, and computers and the internet have greatly facilitated them. One long standing idea is basic income (Wikipedia:Basic income) which would grant every citizen a basic minimum income from the state. This would certainly enable more people to work unpaid on projects they would choose themselves. Another proposal to encourage this and foster community is Open Money. It is still rather a term than an actual concept, but let me now talk about some of the thoughts and ideas that surround it.

The current monetary system

First, let's have a brief look at how things work today. At the root of almost all money are the central banks of each state: the Federal Reserve (FED) for the US-Dollar, the European Central Bank (ECB) for the Euro and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) for the Yen, to name the three top currencies. They create all the money. For every dollar printed, there used to be a corresponding amount of gold stored in the saves of the central bank and the promise of the state to redeem dollars in gold. But for quite some time this hasn't been the case anymore. Most modern currencies are fiat currencies, which means their value is based entirely on the believe and trust of the people that the currency is actually worth something. Money is a mutual agreement, nothing more. No doubt, it is a very useful agreement, otherwise we'd still have to trade cows for sheep which requires always a double-coincidence of wants (Person A has a cow and needs a sheep AND at the same time Person B has a sheep but needs a cow). But in the end, money is still nothing more than an agreement. That's why the central banks can create money virtually out of thin air. Although, if they go too far and create too much new money compared to the goods traded, the value of the currency will decrease.

But the central banks don't put the money directly on the market. Instead, they lend it to private banks at a very low rate of interest – the prime rate (this is always the lowest interest rate in an economy). The private banks in turn lend the money to their customers or other banks at a higher interest rate than the prime, in order to make a profit. This arrangement has some peculiar consequences. Maybe you never thought about it, but how are all the people (and private banks) able to pay back all their loans plus interest? Where does all the extra money that is required for the interest come from?

The infinite growth imperative

One possibility is that some of the people in the system lose their money to others and go bankrupt – the others are now able to pay back their loans plus interest. That's one of the reasons why competition between companies but also between people tends to get tougher all the time. This obviously works against the spirit of community although it enhances efficiency. Another way of getting to extra money is that the central bank simply prints more, or lowers the prime interest rate, which has the same effect because then private banks will be able to borrow more money into existence. But if you have the same amount of goods and services traded and increase the amount of money in circulation, it won't take long and people will notice. The value of the money will decrease. A pound of bread may have cost 5$, now it costs 7$ – that's what's called inflation. To prevent this from happening on an exorbitant scale, the economy needs to grow with the money supply. The idea is that if more things are traded in an economy, more money can be created without devaluating the currency. This new money can then be used to pay back the interests after a while and the circle starts anew. That is the source of the growth imperative in our economies. But how can an economy always continue to grow? One way is to increase the demand for products: more products are sold and more money can be created to compensate. This worked very well during the industrial revolution when people actually gained in welfare when they were able to buy more things. But today, in the industrialized world it is very difficult to sell ever more products. A solution is to manufacture less durable products so people will have to trash them sooner and then have to buy new replacements quicker. You can see this everywhere. Companies that produce too high quality can't sell enough in the long run, so they drive themselves into bankruptcy. Another way for the economy to grow is to have companies take things that previously were free, turn them into a product and charge for them, like for example bottled water. Or Starbucks can charge double the price for a cup of coffee, which is justified by the added experience. For the economy to grow, there should be as much exchange of money as possible. Small favours or mutual care in a family or community are pressured to be replaced by paid work. The result is always the same: if the economy is growing, more money is needed to change hands. This money can be created by loans – it is virtually loaned into existence. But those loans have interest too, so eventually even more money is required to pay back the interest on those loans. And born is the vicious circle leading to an exponential increase in loans.

Interest obviously also helps making the rich richer and the poor poorer. Because the poor need to borrow money from the rich and have to pay it back plus interest. So this way of running an economy is not only unfair in the long run, but it has a built-in growth imperative which goes at the expense of the environment. Also, although efficiency is increasing, shorter working hours are nowhere to be seen, because people need to work more in order to earn more money to buy more stuff to keep the economy growing (because individuals are paid for the work done rather than for the work actually needed). The problems of this system manifest themselves most dramatically in

- financial crises caused by speculative bubbles, currency volatility, or similar

- the problem of supporting the growing percentage of retired people that don't produce money but still need to be cared for (which means in the current system: paid for)

- increasing environmental impact (leading to pollution and climate change)

While the current economy cries for more products to become commercialized in order to keep the money supply growing, free and open source culture strengthen the non-profit sector and continue to produce value without charging for it. While information doesn't need to be scarce because it is a non-rival good (when you share information you don't lose it), the physical resources of our planet are really scarce indeed (oil, rain-forests, etc). But paradoxically intellectual property rights try to make information artificially scarce while at the same time the economy needs to grow infinitely, depriving the physical world of its scarce resources in the process. It should be exactly the other way around!

You won't be surprised to hear now that I have come to the conclusion that this can't go on forever. So what about solutions? There have been numerous proposals to improve the current system, some more radical than others. But none have been tested on a really large scale, which makes evaluating them very difficult. The truth is that the motivations, interactions and the resulting individual and group behaviour of the whole population of earth is so insanely difficult to predict that I don't think we have much of a chance to know whether a proposed economic system works as desired or not without trying it out on a large enough scale.

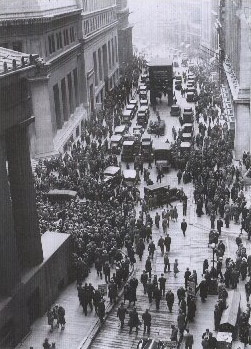

Demurrage

One way to tackle the problem of interest is to abandon it and replace it with demurrage: a fee for holding money over a given amount of time. This concept was proposed (among others) by the German economist Silvio Gesell around 1900. The largest experiment putting this theory into praxis was when the Austrian town of Wörgl introduced its own currency with demurrage in 1932, when people were saving their money during the Great Depression instead of putting it into circulation again. In such credit crunches, central banks usually lower the prime rates and print more money to get the economy going again, but in times of great uncertainty, people tend to hoard this new money too and the measures have no effect. In Wörgl, people were required to regularly purchase stamps that were attached to the money in order to keep it valid. That way the function of money as a store of value was abolished and it functioned only as a medium of exchange and a unit of account. The experiment was a huge success: people had to spend their money in order to pay less demurrage which resulted in faster circulation of money and rapid growth in employment. Unfortunately, in 1933 the experiment was terminated by the Austrian National Bank on the grounds that it was a threat to the Bank's monopoly on printing money and soon unemployment was on the rise again.

Today, instead of requiring stamps on paper money, the demurrage can obviously be subtracted automatically from electronic bank accounts. With interest based currencies, you gain money when you hoard it, with demurrage you lose it. So you can't invest your saved wealth in money and expect it to grow. This leads to investments that have a high long term return, as opposed to the short term thinking and infinite growth imperative that dominates the current system. Suddenly, it's more worthwhile to invest in a forest and keep it intact to continue to harvest smaller amounts of wood over a very longer period of time, instead of chopping it all down right now and invest the earnings on the financial market which makes for a higher profit in the short term.

Community currencies

The national currencies issued by the central banks are far from the only currencies. Money which is not legal tender is often called scrip. Frequent flyer miles or similar loyalty programs can also be thought of as currencies and there are many alternative or complementary currencies that are in use in combination with standard currencies. Some of them make use of demurrage, others don't. A subset of complementary currencies are local currencies which can be used only in a small area. This stimulates the local economy and strengthens the sense of community in a town or area. That's why they are also often called community currencies. One of the first modern complementary currencies is the Ithaca Hour. One Ithaca Hour is supposed to be worth as much as one hour of work done (or can be changed into 10 US-Dollars). They are only redeemable in the city of Ithaca (NY). Because Ithaca Hours don't have demurrage and somebody has to print them, the issuers of the money have to face the same challenges of monetary policy as all the central banks. Too much money in circulation will lead to inflation, too little to deflation. On the other hand, things are simplified by the fact that Ithaca Hours circulate only in a small area and new money is usually inserted into the system by interest-free loans to locals or grants to local non-profits.

An entirely different approach is mutual credit. Most of these systems are called Local Exchange Trading Systems (LETS). There is no physical money, instead the system is based on central bookkeeping, usually electronically and accessible through a normal web browser. Each participant has an account and when he pays another participant, the amount is simply subtracted from his account and added to the other's. This concept can also be thought of interest-free loans and there is no problem with having a little minus in your account. But if you only buy products and services through the system without giving anything back, your account will go deep into minus at the expense of the other participants. This is usually dealt with caps on negative balance or the participants might be able to look at the account balance of anybody before doing business with him. Also LETS are often local or limited to only a few hundred participants and a network of trust in a community holds people accountable. LETS don't need to worry about monetary policy because money is only created in the instance of the transaction – the system is thus self-regulating.

A interesting project which is still in its infancy is Ripple, an effort to develop an open source peer-to-peer protocol to exchange money all over the world. At the core of Ripple lies the idea that within a network of trust between peers, transactions can be made without the need for a third party like a bank that charges for them. Another proposal is to use units of energy as currency. Coupled with smart grids, radically distributed energy production might become a reality: people would sell energy, for example produced by solar panels on their rooftops. Maybe half of the price of products to purchase would have to be paid in energy units, the other half in a normal currency. The energy part of the price would be exactly the energy that is required to produce and distribute the product.

There is a huge number of different community currencies. Many new networks choose to experiment with the system's mechanics or adapt it to local circumstances. Although many projects emphasize on local communities, there are also lots of networks that can make transfers all around the world and currencies that have either floating or fixed exchange rates to other community or national currencies. Community currencies need not be centered around geographic communities, there are also communities on the internet. For example virtual worlds like Second Life or World of Warcraft feature their own in-world currencies. They might be a suitable place to experiment with new exotic currencies on a large enough scale as there are often thousands of players in these worlds.

Conclusion

Obviously, no complementary currency has made the breakthrough into mainstream yet. But the ongoing financial crisis will undoubtedly make them more attractive. I sincerely hope that sooner rather than later someone comes up with a system that scales well and that favours long-term investments and the spirit of sharing and community. Complementary currencies will probably continue to exist alongside our current currencies for a long time. If they become mainstream, they will enable more people to make a living from free culture. And our children will be thankful to us if they still have a planet left to live on when they are our age.