Fab Mob Reciprocal License for the Legal Contractualisation of Commons

Source

* Source: The legal contractualisation of commons: Towards a model of reciprocal licence for "La Fabrique des Mobilités" .

Status

Intro and part I-II, without tables, translated by Pascale Garbaye, January-February 2018

Note the translation is still subject to corrections and improvements.

Still to be translated:

- end of Part II - Chapter Reciprocal Licences (5 pages)

- Part III - Recommandation for "La Fabrique des Mobilités" (5 pages)

- the 2 appendix (charter of values and reciprocal licence) (6 pages) - idem

Text

The subject of this study is to consider the possible terms of a contractual frame for the commons provided, created and developed within "La Fabrique des Mobilités" framework, in collaboration with all the players involved.

This study follows an initial reflection conducted in the "Livre Blanc", published in June 2015, under section "Establishing a common law for "La Fabrique des Mobilités".

Among the recommendations in this first article, we particularly considered that the "Fabrique des Mobilités" could be a regulatory body, by offering legal tools to its members that would enable them to govern the terms and conditions for their participation in the creation, use or even exploitation of commons.

Thus, a contractual scheme was proposed, depending on the level of commitment intended by the protagonists and the interactions that might exist between them. This scheme foresaw a "funnel-shaped" contractualisation: from a simple approval to a Charter of Values towards "open" licences contractualisation, to the possible development of suitable bipartite or multiparty partnerships, favouring reciprocity.

Since then, our aim has been to compare this contractual scheme with the needs expressed by the members of "La Fabrique des Mobilités" on current practical projects, to validate the analysis in relation to emerging contractual practices, particularly in the field of reciprocal licensing and finally, to propose possible and original contractualisation models.

This note is the restitution of this work.

It leads to the proposal of two documents:

(i) A "Charter of Values", designed for all members of "La Fabrique des Mobilités".

This Charter displays the conditions under which the resources are drived and managed within La Fabrique, for exclusively non-commercial purposes and on condition of sharing all copies and versions derived from these resources with other members.

(ii) An operating licence of the resources,

including commercial, available for members who contributed to their creation, enrichment, improvement or development, subject to an equitable remuneration to other contributors.

The existence of commons in our positive law is enshrined in article 714 of the Civil Code, which wording remained unchanged since the law of April 1803 the 19th. Since the general definition given by this article, the acceptation of commons was enriched, both by the law, which regulated certain categories of commons, and by schools, groups and/or communities which tried to implement licences to administer their use or even commercial exploitation, under conditions of reciprocity.

Thus, there is a kind of "taxonomy" of the commons, which can be identified according to their nature and mode of governance.

As for their governance, the only issue we consider in this study, two main contractualisation models coexist

(i) Public access to commons under open licences, generally the widest possible,

(ii) Conditional sharing of commons within a community of interest, in the context of reciprocal licences.

In our opinion, as soon as the "Fabrique des Mobilités" purpose is to create a platform for sharing information and resources between the different mobility actors, with the institution of respective rights and duties between the parties, the reciprocal licencing model, rather than open licences, should be choose.

Then, the question is "how" we can propose possible contractual terms.

After reminding the current acceptations of commons (I), this study looks into ongoing licences proposed or implemented to regulate the use of commons in view of the double objective to safeguard openness and reciprocity (II) and makes recommendations on potential contractual tools for "La Fabrique des Mobilités" so that emerging commons can be exchanged between members, on a non-commercial or commercial basis (III).

I. DIFFERENT ACCEPTATIONS OF COMMONS

In addition to the "classic" conception which, in general, applies to all commons (A), there is a specific category of commons to the transport and mobility field, recently recognised by the legislator: data of general interest (B).

A. Commons, in general

Today, the concept of commons can take many legal meanings, provided both by the law and by the choices of communities. It can be something that belongs to no one and its use is common to all (1), a good whose use is allowed to the many (2) or any results coming from an altruistic action conducted by a community of persons (3).

1. Thing that belongs to no one and its use is common to all

The first definition of common goods is given in article 714 of the Civil Code

"There are things that belong to no one and whose use is common to all"

Res communes usually referred to in Article 714 are natural things, such as air, seawater or running water, and some physical resources, such as pastures or fisheries.

This classic definition can also cover resources established more recently by contemporary legislators. Thus, public data perfectly match with the legal regime of common things, in that they do not belong to the public person, who physically holds them but must be open to the many, according to a legal redistribution mechanism.

Established since the CADA law of 17 July 1978, the policy of open access to public data is enjoying a new boom.

The law n° 2016-1321 of October 2016 the 7th, referred as "Law for a digital Republic", obliges all administrations (ministries, local and regional authorities, public institutions, etc.) to make any administrative document published in electronic format generally and systematically available to the public, "in an open standard, easily reusable and exploitable by an automated processing system".

2. A good whose use is allowed to the many

In addition to the definition of the Civil Code, another acceptation of commons appeared, based on the idea that commons are not necessarily defined by their essence but also by their function: all things which are freely accessible and usable would be common.

This applies when a property owner transfers its ownership to others, either fully or in part, temporarily or permanently, according to a predetermined and non-discriminatory manner.

Thus, according to this line of thinking which underpins the "open-source" concept, ownership itself becomes an alternative source of commons. Software, data or other content distributed "under free licenses" is the result of the willingness of its authors to share its use but remain their property

An "open-source" license is always open under certain predetermine conditions and reservations. Thus, the violation of the free licence terms is an infringement on the authors' intellectual property rights by counterfeiting them.

Therefore, contrary to popular belief, open licences are not the negation of ownership but an altruistic and disinterested development of it.

3. Any results coming from an altruistic action conducted by a community of persons

With the growing and structuring commons movement, the concept of "collaborative commons" appeared, according to which commons become not only natural things but also "human things".

In a society where donation and participation, sharing and feedback of experience, as well as collaboration, are favoured, human activities are now released from the grip of individual appropriation to become things that can be exchanged and even valued within communities of persons or interests.

Besides these three traditional conceptions, a new acceptation appeared in the field of transport: data of general interest, which definition appears to be a new typology of commons.

B. Data of general interest in the field of transport

Submitted to the Secretary of State for Transport, Sea and Fisheries in March 2015, the report called for the creation of a new category of data, data of general interest.

This report has been implemented in the law n° 2015-990 of August 2015 the 6th, referred as the Macron law. This law introduced a new article L1115-1 in the Transport Code, which provides that data, on regular public transport services for passengers and mobility, must be available for users information freely, immediately and free of charge.

Subject to the decree implementing this provision of the Macron law, which is still being reviewed by the Council of State, public transport services, as well as private companies, mobility services and AOT route planners should be subject to this obligation of free and open dissemination and access to the above-mentioned data.

Therefore, this law, implementing the recommendations of Jutland report, creates the new category of data of general interest, understood as private data in nature but their publication can be justified due to their interest to improve public policies.

These data of general interest come from three sources

- Data from public service delegations;

- Key data coming from grant agreements;

- Data from private companies necessary to INSEE surveys.

Since their objective is to be distributed and shared as widely as possible, data of general interest are undoubtedly equivalent to new commons.

Thus, commons would not be only determined by common use or a property rights but also by a purpose, the one whose pursues an objective of general interest.

These commons existing in various ways, can their administration, i.e. how they are used in common, be subject to contractual modelling? According to their nature? The communities who use and exploit them? And possible operational modes, allowed, conditioned or prohibited?

There are currently different licenses that govern the use of commons. Some of them are still looking for. Others have to be invented...

II. ON-GOING LICENCES PROPOSED TO REGULATE THE USE OF COMMONS

The conditions for the governance of commons by the contract are subject to two main models of licenses: open licenses, making commons available to all (A) and reciprocal licenses, making the use of commons under conditions of sharing and remuneration rules, within a community of users (B).

A. Open licences

As stated above, the "open source" model is based on a conception of commons as properties belonging to a sole owner but which use is allowed to all, by the altruistic will of the latter.

From this point of view, a "proprietary" property can be considered as a common if the owner allows its use to the many.

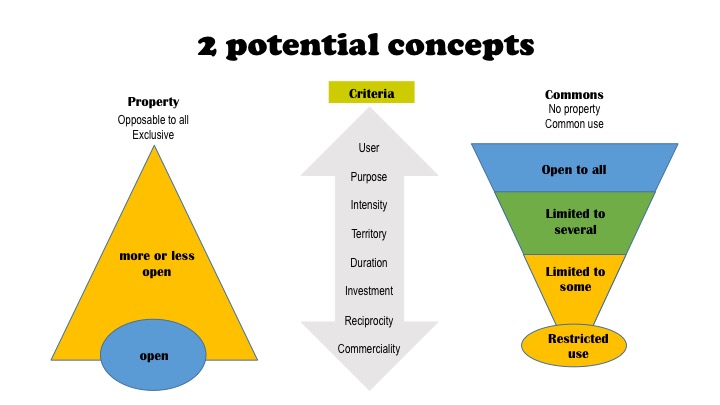

Thus, there are two possible concepts leading to this opening up. A good that, by nature, doesn't belong to anybody or a good which owner "leaves" his property can be opened.

And in each of these two schemes, there can be several degrees of opening: from the most closed to the most open or vice versa, from the most open to the most closed. In the first case, the owner decides to open a property that, by nature, is closed and in the second case, the community can decide to close a resource by nature open, according to a progressive scheme and criteria which can be the same.

These criteria could be the user identity, the nature of the open matter, and intensity of its intended use, a particular territory, the period of use, an investment to protect, an expected compensation or reciprocity or the commercial or non-commercial nature of the use.

In all cases, contract is the tool of opening up or closing up. Usually considered to be a licence, this contract can, depending on the acceptation used, be an exclusive, open or reciprocal licence.

In this study, we 'll focus not about "proprietary" licence but about open or reciprocal licences.

Several categories of open licences include software (1), other creative works (2) and public data (3). However, principle of these licences is criticised (4).

1. "Open source" software

The "Proprietary" scheme above applies perfectly to the logic of software granted in "open source".

Some "proprietary" software can indeed be freely distributed, for non-commercial use, under: - "Freeware" model, when authors have abandoned their intellectual property rights, software is free to use, without financial compensation or specific obligations, - "Shareware" model, when users are, first, invited to test software and choose to make a financial contribution if they are satisfied.

There, opening-up operates within a conditioned scheme.

The concept of "free" software has been set up by Linus TORVALDS (Finnish), and, in order to fight against office software companies' monopolies, the sources of Linux software have been publicly available, free of charge.

This free software model, also called "copyleft", is based on the principle that software should not be considered as a saleable product, but as a resource. Thus, its source code is available for free to everyone, while utilities services, maintenance, consultation, integration, etc. attached to this software are generally provided against payment.

The conditions for the use of free software are governed by an "accessible source" or "open source" licence, which main models are:

- GNU GPL (General Public Licence) and GNU LGPL (Lesser General Public Licence), both designed by Free Software Foundation,

- NPL (Netscape Public License), offered by NETSCAPE Society on its browser Communicator.

The features of the main "open source" licences are detailed in the following table.

2. Extension to other creative works : Creative Commons' model

"Open source" user licences have been proposed for other works than software, but they only apply to a specific category of works: Cecill for software, LEL Licence for art work, Free Music Licence for musical works.

In 2001, Professor Lawrence LESSIG, from University of Stanford, created the "Creative Commons" model, in order to offer authors of creative works an alternative to the traditional patterns for their communication towards the public and, thus, further their sharing while keeping their protection.

Owners of intellectual property rights can, currently, select six licences for their works, according to exploitation they intend to give them.

1. Attribution (BY): The rights owner authorises any exploitation of the work, including for commercial purposes, as well as creation of derivative works, which distribution is also allowed without restriction, provided that the name of the author is quoted.

2. Attribution + No Derivatives (BY ND) : The rights owner authorizes any use of the original work (including for commercial purposes), but doesn't allow the creation of derivative works.

3. Attribution + Non Commercial + No Derivatives (BY NC ND) : The rights owner authorizes any use of the original work for non commercial purposes, but doesn't allow the creation of derivative works.

4. Attribution + Non Commercial (BY NC) : The rights owner authorizes any exploitation of the work, as well as creation of derivative works, only for non commercial purposes (commercial uses are subject to his approval).

5. Attribution + Non Commercial + Sharealike (BY NC SA): The rights owner authorizes any exploitation of the original work for non commercial purposes, as well as creation of derivative works, provided that there are distributed under the same licence than the original work.

6. Attribution + Sharealike (BY SA) : The rights owner authorises any exploitation of the work, including for commercial purposes, as well as creation of derivative works, provided that there are distributed under the same licence than the original work.

3. Public data user licences

Under the above CADA law and "For a Digital Republic" French law, access to and reuse of public data may be subject to licences laying out their associated rights and obligations, on the basis of licences more or less open.

To date, several licences coexist:

ETALAB mission promotes a fully open, free, non-exclusive and free of charge licence, which promotes the broadest possible re-use, by allowing the transformation, reproduction and commercial redistribution of data, including their adaptation and combination with other data, subject to the mention of the source and last update of the data.

As for data defects and irregularities, the "producer" does not offer any guarantee, nor does he insure that their supply can be continuous. However, he guarantees that data does not contain any intellectual property rights belonging to third party. If it owns them, he shall transfer the rights on a non-exclusive basis, free of charge, for the whole world and for the entire duration of the rights.

Recently, ETALAB licence was updated, to include the updated provisions of the law "For a Digital Republic". Particularly, it takes the re-use of public information containing personal data into account, subject to the "Informatique et Libertés" law n°78-17 of January 1978 the 6th.

Other types of open licences – such as « Open Government Licence (OGL) », « Creative Commons », described above, and « Open Data Commons » – not initially foreseen for open data but for the release of intellectual property rights, can be easily adapted to opening data.

Some French institutions shall adopt these licences. OBdL et ODC-By licences appear to be the more commonly used.

"L'Agence du Patrimoine Immateriel de l'Etat" (APIE), provides Public Information Licenses (PIL) which are not "free licenses". Subject to a fee for the public person, it allows the re-use of public data under certain conditions.

The duration of these licenses may be unlimited or limited.

These licenses seem to fall into disuse in favour for "open" models.

Even so, it has to be said that, in France public data access and re-use have been partially achieved: few public persons released their data and its reusing modes is facing resistances.

This is why, the law "For a Digital Republic" created a public service for data.

According to Article 11 of this law, administrations should not hinder re-use of their published public databases, except for data which have been produced or received in the exercise of a public service mission, of an industrial or commercial nature, subject to competition.

To this end, a list of free re-use licences for these public data will be proposed, determined by decree and revised every five years.

When an administration wishes to use a license that is not on this list, this licence has to be, first, approved by the State, under conditions determined by decree.

To date, these two decrees have not been published yet.

4. Criticisms of the "open source" model

Theorists and practitioners of commons have criticized the "open source" model.

This model was first criticized for being inadequate in relation to the concept of commons, which is based on the idea of resources "governed" by a community of interest.

Valérie Peugeot, researcher and chairwoman of VECAM, defines commons by the three dimensions that characterize them: commons are (i) resources (ii) subject to a collective rights and obligations system (iii) which use is governed by a community.

Yet, open licences, previously described, are unilateral licences which opening-up, terms and conditions of the opening-up, are decided by the only will of the initial holder of the resource.

Moreover, an "open source" licence aim to disseminate the work to the many, without keeping in mind the idea of reciprocity from licences' users, neither interaction between them and the initial holder of the resource.

Imposing certain conditions on the opening-up of a resource, as in the open licences scheme, is not the same thing as agreeing on the opening-up conditions, that require, of those who benefit of the opening-up, a positive action of reciprocity, whether material, financial or ethical.

"Open" Licence model has also been criticised for not distinguishing non-commercial or commercial exploitation. This allows commercial entities, which have not contributed to resources or financed their creation and development, to use them for free, even to make their own, thus creating a state of unregulated competition and a new form of parasitism.

Paying close attention to these practices, the article 8 of the "For a Digital Republic" law provided protection for a new class of commons, the common informational domain. The aim of these provisions was to "protect the common resources of the public domain from ownership practices that lead to denying access to them", by allowing authorized associations to take legal proceeding to defend this common domain and to put an end to any attempt to exclusive reappropriation.

However, these provisions have not been taken up in the law that was finally approved, due to the opposition of several actors in the literary and artistic property field (SEPM, SACD, SNEP, FNPS, SNE …), who argued that there were imprecise and dangerous for copyright protection.

Whatever, criticism against "open source" licenses is now the basis for the current thinking of reciprocal licences.

B - Reciprocal Licences

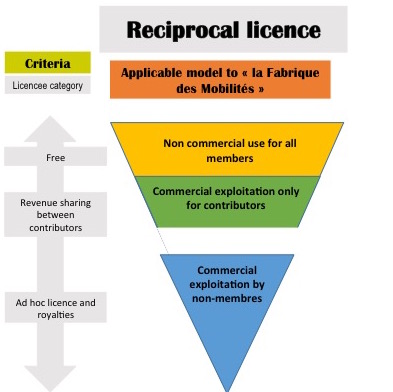

In opposition to the "open source" model, promoting the dissemination to everyone, reciprocal licences set up principle and conditions for the sharing of common. It's restricted to members of a community and depends on respective contributions for the common.

Reciprocal licences usually provide for increasing restrictions, depending on the categories of common users, in order to ensure reciprocity on the conditions of this sharing.

Those restrictions are usually based on the following main principles:

a) The common can be used by all members of the community for non-commercial use

b) Commercial exploitation of the common by members is possible, under the condition of a remuneration to the contributors of this common

c) Commercial exploitation of the common is prohibited to third parties, non-contributors, unless they pay a fee under a specific license

Based on four different philosophies, four major types of reciprocal licences can be implemented

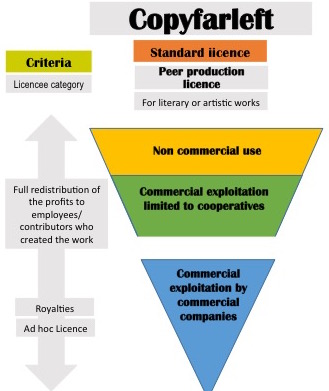

1. "Copyfarleft" model

Dmytri Kleiner has developed the "Copyfarleft" licence model, especially in his publication “The Telekommunist Manifesto” (2010).

The principle is that only a non-commercial use of a resource is free In the case of a commercial use, only certain legal entities may effectively exploit it.

Thus, commercial use of the resource is restricted to companies owned by its employees and cooperatives, provided that all financial gains, surpluses, profits and benefits generated by the enterprise or cooperative are redistributed to employee-owners.

Therefore, any use of the resource is not allowed to private, non-cooperative companies that seek to generate a profit from this resource.

Commercial entities may use the common provided they pay a fee, under an ad hoc licence, apart from free licence.

Therefore, the main criterion of this licence is the cooperative nature of the resource users.

To date, the "Copyfarleft" model is illustrated in the "Peer Production License" model.

It's intended to apply to all literary, scientific and artistic creation protectable by intellectual property right, whatever the mode or form of expression, including digitally.

This licence can be modelled as follows:

The main objective of the "copyfarleft" model is to prevent the risk of fierce competition from economic entities, which may take advantage for themselves of a common achieved by others.

However, it introduces a bias in that commercial exploitation is reserved for categories of entities, based on their legal status and not on their effective contributions. Thus, any commercial entities are excluded even those that would have contributed to the common.

In their article "une nouvelle proposition de Commons » (online « Journal of Peer Production » -n° 4 jan. 2014), Miguel Said Viera and Primavera de Filipi highlighted that this approach was too reductive

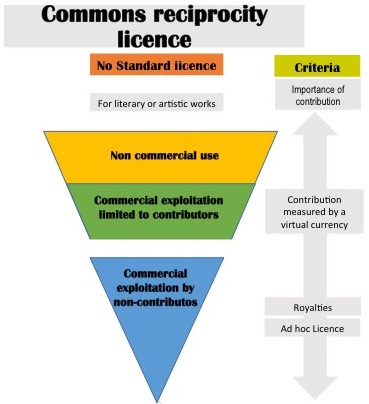

2. "Commons Reciprocity Licence" model

In the article mentioned above, Miguel Said Viera and Primavera de Filipi propose to include a reciprocity clause as an alternative to "copyfarleft". Only contributors of the common may commercially or not exploit common, regardless of their legal status.

The main criterion of this licence is to contribute to the resource.

For a non-commercial use, any contributor to the resource benefits from a free licence. Their contribution is measured by a virtual currency, the "Peer-Currency".

This currency must, also, allow assessing remuneration of all the common's contributors when the resource is used for commercial purposes. "Open Value Accounting" model is a variation of "Commons Reciprocity Licence" model. The contributions are measured by a rating that each contributor receives from his or her peers.

Non-contributors may only commercially exploit a common under an ad hoc licence concluded with the contributors in return for payment of a fee.

To date, "Commons Reciprocity License" model has not given rise to the writing of a standard license. However, it can be modelled as follows:

The main advantage of the "Common Reciprocity Licence" model is to allow contributors to commercially exploit the common and receive remuneration commensurate with their contribution, without exclusion because of their status.

In this model, the complexity lies in how the contributions are assessed. A virtual currency measurement system could be too complex to implement and manage. It might, also, introduce an element of arbitrariness in the assessment of the different modes of contribution.

The initiators of the "Commons Reciprocity License" are aware of this risk, which they mention in their article:

"One of the most important is the determination of the "exchange rate" between different types of works. In other words, how can we measure individual contributions (in different fields) through tokens? How many token would be allocated to a user who contributes to the commons through an image, video or text? Should derivative works or improvements be rewarded with fewer token? Should the system have to take into account a measure of the quality or artistic merit of these works? And if so, who would be competent to carry out such evaluation?"

However, unlike rating system of "Open Value Accounting" model, the advantage of an "exchange currency" system is to confer an objective system for measuring the contributions.

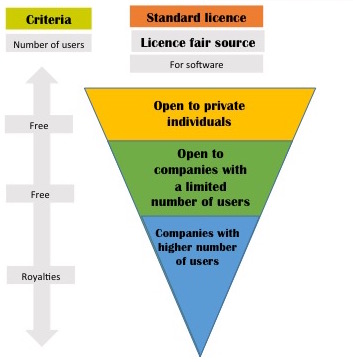

3. "Fair source Licence"

Other licenses have been developed to allow common goods sharing so that right holders can receive remuneration, while supervising their exploitation. Thus, "Fair Source Licence" is based on sharing source code of software or software development, while allowing right holder(s) to receive income from the exploitation of this property.

This licence is granted free of charge to private individuals and companies, subject to a limited number of end-users within an enterprise (including its affiliates).

In a company, if the number of users exceeds the above-mentioned ceiling, the licence is subject to payment of a fee.

Therefore, the main criterion of this licence is the nature of the user (private individual or company), and, for companies, the number of the resource users.

The mechanism of this licence can be modelled as follows:

Therefore, the "Fair Source" license corresponds with much more liberal organization of the community constituted around the common. Indeed, there are no specific compensation obligation between contributors and users, except for companies, above a certain size, which would pay a fee.

Besides, as it is, this licence doesn't have a system for measuring the contributions and assessing remuneration that would be owed to contributors.

The other licence implemented, in order to ensure remuneration for the holders of common rights, is the "FairlyShare" licence. The object is to give free access to commons in the contributory community, but subject to a fee in the commercial sphere.

Therefore, the licence holder undertakes to do his best to define an area and a limited period for exploiting its rights, and to identify the contributions and their authors. This things being done, he must define and distribute the profit share allocated to contributors, according to best practices (failing that, the share is 50%).

Finally, he must commit to a number of societal and environmental values, including the UN Global Compact, Social and Environmental Responsibility and the journalists' code of ethics.

The "FairlyShare" licence is quite similar to the above-mentioned "Commons Reciprocity License" model. The operator of a common must elaborate and implement a system in order to distribute profit share to contributors, for the commercial exploitation of the common.

This licence can be modelled as follows:

However, the system implemented is more liberal. The allocation system is not defined by the community, but is left to operator's free choice and responsibility. Thus, in this licence, there is no system for measuring contributions, through virtual currency or any other means

III RECOMMENDATIONS FOR "LA FABRIQUE DES MOBILITÉS"

In the first instance, "La Fabrique des Mobilités" might promote to its members the adoption of open or reciprocal licences, as described previously. Thus, according to the "Livre Blanc" article published in June 2015, "La Fabrique" would play the role of mediation body, that is to say a space for exchange and collaboration between its members, without obligation to adopt precise contractual frameworks.

Information should be provided to members regarding those various licences, their nature and content that "La Fabrique" members may or may not adopt. If so, they would have to choose which one they wish to use, this choice being their own and sole responsibility.

On a more proactive approach, "La Fabrique" might encourage members to privilege certain licences, make a choice between open or reciprocal licences, or impose some of them in the course of its operation. Thus, according to the "Livre Blanc" article, "La Fabrique" would operate as a safety regulator.

If "La Fabrique" wished to promote reciprocal licences, it might also privilege certain models, among reciprocal licences aforementioned, or create other models specific to it.

In our view, this is the purpose of "La Fabrique des Mobilités", which is to bring together different actors, creators and contributors of many resources. The aim is potentially a commercial exploitation of these resources, after a process of experimentation and exchanges, which can be first non-commercial.

Thus, the reciprocal licencing system appears to meet this vocation as it enables to distinguish non-profit activity and commercial activity, a typology of contributors and methods of contributing.

A reflection should be undertaken on the opportunity to select a model.

"Copyfarleft" model that excludes some categories of users (that is to say commercial companies for the benefit of cooperatives) seems to be inappropriate with "La Fabrique des Mobilités" ecosystem. Its purpose is to make actors with different legal status interact with each other, and only few adopt the cooperative model.

"Commons Reciprocity License" model, whose main criterion is contribution, seems closer to "La Fabrique des Mobilités" philosophy. Thus, all contributors, regardless of their legal status, could benefit from the licence and a return on their respective contributions. However, the complexity would be to create a measurement unit for contribution, as an exchange currency.

Therefore, further reflection should be given to the implementation of such system that will allow to value contributions. It would be, especially, a question of including rules on the allocation of this currency units to contributors and the exchange of these units among themselves. Special attention should also be paid to prevent speculative risks or superficial contributions tending to distort the rules. Similar structure to "La Fabrique des Mobilités" in the HR field, The LAB-RH has developed a currency allowing to quantify the commitment of players. It quantifies what they produce for the LAB compared to what they earn.

As for "Fair Source Licence" model, the problem is to use the number of resource users as a criterion for the companies. This system, based on company size for the payment of a fee, doesn't match with the Model implemented by "La Fabrique des Mobilités", which host small start-ups as well as large industrial groups or territorial authorities. Therefore, the use of this licence would potentially entail an unfair access conditions for the players of "La Fabrique des Mobilités", insofar as start-ups could use them for free, while large companies would have to pay a fee, regardless of each other's volume of the contribution. Finally, the "Fair Source Licence" provides for remuneration to the contributors of a resource, based on the revenues generated by its commercial exploitation. However, the model doesn't include conditions beyond a certain number of users, making it insufficient to establish an administration system for the commons immediately reproducible for "La Fabrique des Mobilités".

"FairlyShare Licence" model does not require operators to comply with a remuneration standard model. Thus, each common operator could apply its own system, which could have the drawback of a non-uniform or even dissimilar remuneration of the contributors' contributions.

Therefore, this model does not seem sufficiently organised to be implemented within the framework of “La Fabrique des Mobilités”. Moreover, according to this model, operators of commons are subject to very strict obligations in adhering to societal and environmental standards, which should be monitored. Thus, the application of a "FairlyShare" licence within “La Fabrique des Mobilités” could prevent any control in measuring contributions. Contradictorily, it will require the implementation of a rigorous monitoring system for the respect of societal and environmental standards. These requirements may respond to ADEME's concerns, and in that, constitute an interesting reflection.

Then, "La Fabrique des Mobilités" may want to create its own model of licence.

Regulation of the commons use within this structure, which would be organized around an original model, could be based on the most interesting mechanisms of reciprocal licences, specifically:

a) "La Fabrique des Mobilités" members could use the commons, created within its framework, free of charge and non-exclusive, worldwide and for an unlimited period, for non-commercial use.

Reciprocity would lie in the fact that each member who would provide or use a common to improve or perfect it, within "La Fabrique", would be subject to the same sharing conditions. And in case of enhancement or improvement, the member would undertake to share again this common thus enriched between the members of "La Fabrique", under the same conditions of use.

The users of the commons would submit to a charter of values, laying down the essential obligations to which they should comply. An example of this charter is provided in appendix I. This example is a basis, which can be improved, collegially, by a collective reflection between the members of "La Fabrique des Mobilités".

The charter can be seen as a minimum set of rights and obligations when a new member wants to join "La Fabrique", by simple voluntary membership. Thus, there is no requirement to obtain the express written consent of the members. However, its dissemination should be sufficient to enable everyone to know about it.

The criterion for the application of this charter would be non-commerciality and its enforceability criterion would be the status of "La Fabrique" member.

b) Only "La Fabrique" actors who contributed to the commons could exploit them commercially, under the condition of a remuneration to every contributors, in proportion to their contributions.

Reciprocity would lie in the fact that each contributor is obliged to reward the other, in case of a commercial use of the commons generated by the latter.

The valuation of each contributor's contributions should be questioned before the implementation of such a commercial licence.

As mentioned before, measuring contributions through virtual currency, as suggested by the Commons Reciprocity License, could be complex to implement.

However, the valuation of the contributions through "exchange currency" is a relevant idea and provides a way to objectively measure the respective contributions.

Then, consideration should be given to a system that is both simple to implement, so as to avoid uncontrolled operation, and rigorous to prevent any risk of circumvention.

An example of a reciprocal licence designed for "La Fabrique des Mobilités" is provided in appendix II. It can be enhanced by collective reflection.

The purpose of this licence is to apply to all types of resources whether there are data, material property or inalienable rights such as software, graphic creation or any intellectual work.

This license should be proposed for signature to any member of "La Fabrique" who contributes, in one way or another, to create or enrich a common.

The criterion for the application of this charter would be non-commerciality and its enforceability criterion would be the status of "La Fabrique" contributors.

c) The submission of any commercial exploitation of the commons by non-members of "La Fabrique des Mobilités" to the conclusion of an ad hoc licence and the payment of royalties, under conditions to be determined depending on the nature of the commons, the exploitation methods, the duration and the intented territory.

It's interesting to consider this hypothesis in order to allow the dissemination of the commons, brought by "La Fabrique", and return on investment of their contributors.

At this stage, it is difficult to propose a drafting as the situations and interests may be different, and the various actors involved. But its principle should be open to further collective reflection.

The criterion for the application of this ad hoc licence would be commerciality and its enforceability criterion would be the status of "La Fabrique" non-member and non-contributor to the commons

This general model could be modelled as follows:

Thus, commitment to this corpus of rights and obligations would be progressive, according to member's involvement.

A clear distinction would be made between non-members and members of la Fabrique, recognising that members have an advantage in participating and joining a "club".

Distinction between members and contributors would, also, be drawn. Non-contributor stakeholders can be involved in "La Fabrique" but when they start contributing they would join a second closed "club". Then they would be allowed to exploit commercially the commons under condition of fair and reciprocal remuneration to the contributors.

However, non-Members of "La Fabrique" would not be excluded from this marketability, under financial and commercial conditions to be defined on a case-by-case basis.

At this stage, this contractual framework remains a promise. It requires a collective reflection and to be compared with practice of the communities of interest which constitute "La Fabrique des Mobilités".

This reflection on the contractual framework must be combined with a necessary debate on the governance of "La Fabrique des Mobilités". According to the aforementioned article of June 2015, in the "Livre blanc", one of this governance structure tasks would be to allocate resources and regulate their use and, also, to manage conflicts between users.

Thus, "La Fabrique" would become, in addition to a club and a technical platform for sharing resources, a trusted third party in the regulation and management of commons.

APPENDIX I: LA FABRIQUE DES MOBILITÉS CHARTER OF VALUES

Preamble:

This charter is addressed to all members of "La Fabrique des Mobilités" (hereinafter: "You")

"La Fabrique des Mobilités" is a European accelerator. Its purpose is to bring together transport and mobility players, to give them the opportunity to develop and share their projects, to capitalise on feedback and mistakes, in order to develop a common culture of innovation in action

To this end, "La Fabrique des Mobilités" has created several communities of interest (hereinafter: "Communities") to develop open contributions platforms, in several fields related to transport and mobility.

Rights granted to you:

By participating in "La Fabrique des Mobilités", you are allowed to use resources, which are fed and administrated collectively by the different Communities (hereinafter: Commons). The use might be subject to specific conditions imposed by each community under reciprocal licences.

With that proviso, you have the right to:

- Use and share commons between members, in full or in part, exclusively for non commercial use;

- To enrich, complete, improve or perfect the Commons, alone or with several members;

- Create or use copies and derivatives of commons, exclusively for non commercial use;

- Initiate and propose collective projects between the members, on the basis of Commons, their copies or derivatives, exclusively for non-commercial purpose.

These rights are granted to you, worldwide, as long as you are involved in "La Fabrique des Mobilités".

If you bring or create Commons within "La Fabrique", contribute to achieve or enrich them, you agree to submit to the same terms of use and sharing.

Conditions for exercising these rights:

Your exercise of rights, referred to above, is subject to the following conditions:

- If you share any copy or derivative versions of these commons, you should include contributors names by any useful means and include a copy of this charter, or internet address for reference;

- If need be, you have to specify whether you have created a derivative of a Common, identify any changes and give indication of preliminary changes in the Common;

- When you create a derivative of a Common, you may not infringe intellectual property rights of a third party, or, more generally, violate rights of any third party or applicable regulation, unless authors or beneficiaries' prior authorisation;

- You may only use and share the Commons under the conditions of this charter.

Obligation of reciprocity

You agree to share with other members any copies and derivatives of Commons, which you might have enriche, complete, improve or perfect, for an exclusively non-commercial use and under the same conditions as those laid down for the sharing of Commons' charter.

You refrain from imposing any other restrictions and/or restrictions on other members with whom you are sharing.

Warranties and limitation of liability

Subject to the guarantees of public policy required by law, the Commons are provided "as it is", without any express or tacit warranty, including for their content, accuracy or suitability for their intended use. Contributors' responsibility can't be engage, under no circumstances.

Other obligations

By participating in "La Fabrique des Mobilités", you agree to:

- comply with existing laws and regulations and not to undermine third parties' right or public order,

- not to take someone else's identity or give false or misleading information

- inform without delay "La Fabrique des Mobilités" of any difficulty relating to your participation in the Communities and your use of the Commons, under conditions laid down in this charter;

- respond as soon as possible to any request for information from the person in charge of a Community or "La Fabrique des Mobilités".

For infringements of rules related to this charter, "La Fabrique des Mobilités" reserves the right to suspend or put an end to your participation, to inform any competent authority or to take legal action.

APPENDIX II: LA FABRIQUE DES MOBILITÉS RECIPROCAL LICENCE

Preamble

This licence applies to all members of La Fabrique des Mobilités (hereinafter:"Contributors") who have created, enriched, improved or perfected a Common (as defined below).

Commons are available to Licencees (as defined below) under the terms of this licence (referred to as the "Licence"), subject to any specific licences imposed by communities of interest above mentioned.

The exercise of any right on a Common offered by the Licence constitutes acceptance of it. According to the terms and obligations of the Licence, the Licensor (as defined below) offers to the Licencee to exercise some rights presented below, and the Licencee approves the terms and conditions of use.

1. Definitions

a. "Common": a resource collectively fed and managed by one of the communities of interest of "La Fabrique de Mobilités"; b. "Collective Resource": a resource collectively fed and managed within "La Fabrique de Mobilités". A common, in its complete and unaltered form, is combined with other separate and independent Commons into a collective set. According to these licence, a common that constitutes a Collective Resource will not be considered a Derivative (as define below). c. "Derivative": a resource created either from Common alone, or from Common and other pre-existing resources, also fed and managed collectively within "La Fabrique de Mobilités". d. "Licensor": Contributor(s) who make(s) available a Common under the terms of this License. e. "Licencee": Contributor who accepts this User Licence of a Common

2. Exception to exclusive rights

This Licence makes no provision intended to reduce, limit or restrict the prerogatives arising from exceptions to rights, exhaustion of rights or other limitations to the exclusive rights of the right-holders under intellectual property law or other applicable laws.

3. Extent of the Licence

Subject to the terms and conditions set by this Licence, the Licensor grants the Licencee the right to exercise the following rights, on a non-exclusive basis, worldwide and for an indefinite period:

a. use, copy and exploit Common; b. embed Common into one or more Collective Resources, as well as to copy and exploit those Collective Resources; c. create Derivatives, as well as to use, copy and exploit those Derivatives; d. distribute copies, display or communicate Common, Collective Resources and Derivatives to the public, by any technical means; e. extract and re-use substantial parts of a Common, Collective Resource or Derivative when it’s a database.

Above-mentioned rights may be enforced over all media, technical procedures and formats, including the right to make necessary adjustments to the exercise of rights in other technical formats and processes. The exercise of rights, which are not expressly authorized by the Licensor or which he does not manage, remains reserved.

4. Restrictions

Rights guaranteed by Article 3 are expressly subject to and limited by the following restrictions:

a. Licencee can only exploit a Common, a Collective Resource or a Derivative under the terms of the Licence, including digitally. For any copy of the Common operated by the Licencee, including digitally, he must associate a copy or Internet address (Uniform Resource Identifier) of this licence. Using a common, Collective Resource or Derivative, the Licencee may not offer or impose any conditions, which alter or restrict the terms of this License or the exercise of rights granted to the beneficiaries. The Licencee must maintain the established information that refers to this Licence and non-liability. Licencee can’t exploit, including digitally, a Common, Collective Resource or Derivative, using a technological measure that control access or use, which would be in contradiction with the terms of this License.

b. Licencee shall not violate other contributors’ intellectual property rights to the Commons, Collective Resources and/or Derivatives of a third party. More generally, the Licencee shall not infringe the rights of third parties or the applicable regulations, without the prior and written consent of the relevant contributors.

c. If the Licencee exploit, including digitally, a Common, Collective Resource or Derivative protected by copyright, he must keep intact all information on the regime of rights. He must attribute the authorship to the Contributors who have created and/or improved it, by any useful means in respect to the medium or method used. He must provide:

- Contributor(s) name(s),

- The Common, Collective Resource or Derivative’s title if mentioned,

- Whenever possible, Internet address or Uniform Resource Identifier (URI), specified by the Licensor as associated with the Common, Collective Resource or Derivative Version.

As for Derivative, the elements identifying the use of the Common should be listed. Those obligations to establish authorship must be fulfilled by any useful means. Yet, in the case of Derivative or Collective Resource, this information should appear, at least, as visibly as similar information.

5. Commercial use of Common, Collective Resource and/or Derivative.

The rights granted by Article 3 include commercial exploitation of Common, Collective Resource and/or Derivative, under following express terms:

a. The Licencee undertakes to reserve for the Contributors a[XX] % overall share of the turnover, excluding tax, for the commercial exploitation of the Common, Collective Resources and/or Derivative Versions

b. The allocation of this share among various Contributors will be calculated according to "La Fabrique des Mobilités" method, available on its website lafabriquedesmobilites.fr.

6. Guarantee on use rights for Commons, Collective Resources and Derivatives

By making available to the public, Commons, Collective Resource and/or Derivative, under the terms of this License, the Licensor declares in good faith, to the best of its knowledge, that:

a. The Licensor obtained all rights attached to Common, Collective Resource and/or Derivative, necessary to exercise the rights granted by this License and to allow quiet enjoyment and lawful exercise of these rights. This, without the Licencee having any obligation to pay remuneration or any other payment or rights than the part referred to in Article 5 above, within regulatory limits. b. Common, Collective Resource and/or Derivative do not constitute neither a violation of third parties rights, particularly intellectual property rights, civil law or any other right, nor defamation, privacy breaches or any criminal offense against any third party.

7. Commons, Collective Resources and Derivatives "as it is"

Except for the situations specifically mentioned in this Licence, and subject to Article 6 provisions, Common, Collective Resource and/or Derivative are provided "as it is", without any express or tacit warranty for their use.

Except for guarantees on public order required by applicable law, the Licensor will, in no case, be held responsible toward the Licencee for any direct, indirect, material or moral damage arising from the use of Common, Collective Resource and/or Derivative under the responsibility of the Licencee.

8. Cancellation

Any breach of the Licence terms by the Licencee will lead to the automatic termination of the Licence and related rights. However, the Licence keeps its effects towards physical or moral persons for whom the Licencee made available Common, Collective Resource or Derivative under the term of this Licence, as long as they comply their obligations.

9. Various

a. The invalidity or unenforceability of any provision of this Licence, under the applicable law, will not affect other provisions, which shall remain valid and applicable. Without further action by the parties to this agreement, these provisions shall be interpreted to the minimum extent necessary for their validity and applicability.

b. No limitation, waiver or amendment of the terms or provisions of this License shall be accepted without the written and signed consent of the competent party.

c. This Licence represents the only agreement between the parties regarding the Common available, as well as any Collective Resources and Derivatives. Except the elements mentioned here, there are no additional elements, agreements or mandate about Commons, Collective Resources and Derivatives. Any additional provisions that may appear in any communication from the Licencee shall not bind the Licensor. This License may not be modified without a mutual written agreement of the Licensor and Licencee.

d. The applicable law is French law. Any dispute related to the validity, interpretation or performance of this Licence will be referred exclusively to the jurisdiction of the competent courts of Paris.